21st Century Insecure Man

Modern male neuroses in Matthew Davis' 'Let Me Try Again' and Hansen Shi's 'The Expat'

What is the modern young man insecure about? Undoubtedly, many of the same things that Gishimmar the third son of a Sumerian grain thresher would’ve jotted down in his cuneiform scribblings (had universal literacy existed in the Bronze Age). But Gishimmar never knew what being on Tinder was like.

Much has been written this year (much of it—at least when written about in mainstream publications—pointless) about the lack of young male novelists and their works. So why not review a couple that have been published recently?

Male insecurity—by which I mean young straight male insecurity—is a tricky topic. Where there are calls for guys to open up about our feelings, what’s often more sought is the willingness to reveal. The ideal man in this situation offers the key to his mental vault in an act of trust and vulnerability, only for the investigator to discover that nothing’s inside. Or at least nothing objectionable.

But who really wants to read about the happy and well-adjusted?

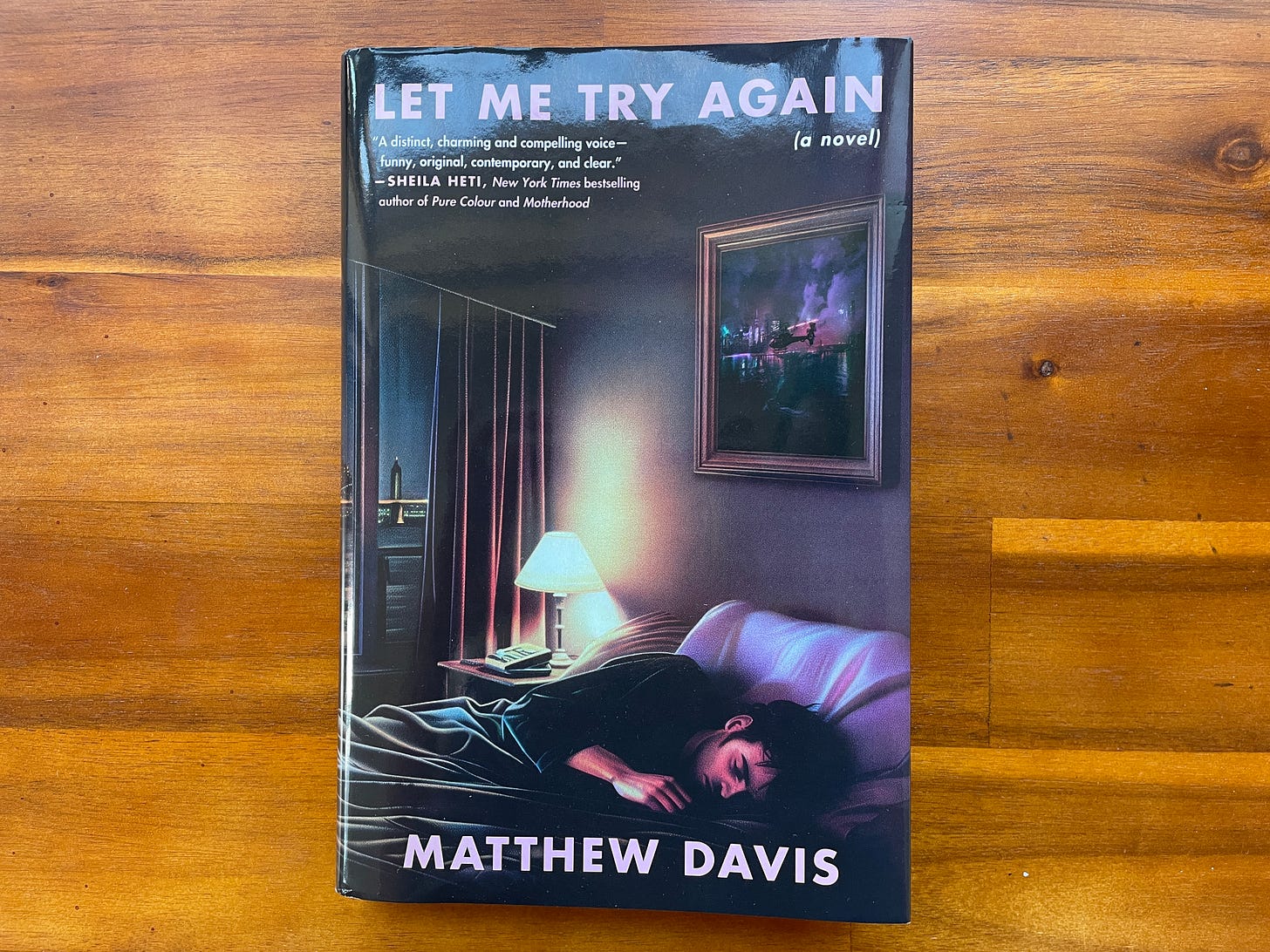

Matthew Davis’ Let Me Try Again engages with this artistic dilemma by taking the comedic approach. The novel’s 23-year old protagonist, Ross Mathcamp, is a ridiculous twerp of a character, a combination of Woody Allen’s Jewish neuroticism and Elliot Rodger’s RPG-like (mis)understanding of human relationships. The novel follows Ross as he attempts to win back his ex-girlfriend, Lora, after he breaks up with her in an overplayed-hand attempt to get her to stop drinking and smoking weed so much.

The problem for Ross is that she was out of his league in the first place (cue Tal Bachman’s She’s So High). She’s from a patrician family, the daughter of a diplomat. He’s a self-described “little Jewish bug to be laughed at.” He does have a supremely high regard for his intellect (the proud owner of a “good brain, a great brain”), but this high IQ usually just manifests itself in disastrous ways. When he proudly shows his sister a draft of his eulogy for their parents, she is aghast to find that it’s all about himself, full of attempts at clever wordplay and lofty references. “It’s just sick,” she says in disbelief.

So he must climb in status. But he can’t do anything right here either. He chooses a career in nursing because on a per-year-of-education basis, it’s one of the most lucrative. Chicks dig dollars, right? But his occupation hardly makes him a ladies man. The only meaningful reaction he receives is from an older female nurse who assumes he’s into “raw-ass gay-ass gay sex” because of his profession.

His brilliant therapy-assisted plan is to adopt Goldberg (yes, the 90s pro-wrestling superstar) as his aspirational figure because he was a Jewish guy with a Jewish name who had the “best body in the business, a truly monster physique.” Massive pecs and non-surgical rhinoplasty would surely add +4 to charisma, thus enabling the completion of the Lora quest.

Still, there’s something endearing about the rather child-like Ross. Despite his obsession with sex (the word “cuck” seems to appear every other page: Ross’ friend tells him that his “little strategy of breaking up with [Lora] and waiting for her to come back was one of the most cucked maneuvers in the history of cuckkind”), he is very squeamish about sex itself. When he matches with a woman on a dating app and she is on her way to this place, instead of being excited at assuaging his bruised sexual ego, he shuts himself in his bathroom, feeling sick that a “dating app whore” is on her way. When he learns that his recently deceased parents liked to engage in threesomes while on vacation, he celebrates their death:

Now this was just sick. Sick, sick, sick. What a terrible thing for a son to have to see. It was a great relief to me that they died in a helicopter accident before getting a chance to meet with this internet hooker.

As repugnant as that thought may be, Ross comes off more like Kevin McAllister, stomping up the attic stairs as he says he hopes he never has to see his family ever again, than Lizzie Borden. And when he recalls his own unplanned birth:

Within a few months my teenaged mother was pregnant (with me, Ross!), and out of some secular pro-life sentiment, decided to keep the damned thing (smart!).

I could imagine fetal Ross, doing a little happy dance upon hearing that he wouldn’t be aborted.

Unlike many other so-called alt lit novels, I enjoyed Let Me Try Again a lot because it’s at least funny and has a pulse. When Ross falls over on his scooter, as he’s splayed out on the ground, he wonders if he should exaggerate his injuries to gain sympathy from the “two beautiful, large-breasted human women” who witnessed his embarrassing accident. And when Ross tries to ingratiate himself with Lora’s father, Ted, by saying how much Lora resembles her mother, Ted takes offense, demanding to know if Ross is expressing a desire to sleep with his wife. Poor Ross, the little Jewish bug.

Ross’ predicament highlights this new era of male insecurity, of not just being surpassed by women, but then being looked down upon by those same women. Societal expectations, including those of many otherwise progressive women looking for boyfriends and husbands, require men to be equal or superior in some way. But those ways are becoming more scarce, which means losing women to a narrowing pool of elite men (see Ross’ hatred of “Thirty-Year Old Losers” who have nothing going for them but inherited wealth and status and who then parlay those ill-gotten gains to steal the likes of Lora from “nice Jewish boys” like himself).

writes that “what many of these guys resent is not merely their own empty sex lives but specifically that women are able to capitalize on their sexuality in ways they can’t.”1 There is an overabundance of rage-bait out there of young men seething at OnlyFans girls and their ilk. But what’s apparent is that a significant part of that resentment is jealousy over the fact that these girls can become relevant, even sometimes rich, by using their sexuality in a way that most guys can’t. This is the trap of a sex-sells culture for men: if sex appeal is all that matters, and—in a heterosexual context—female sexuality is worth so much more than its male counterpart, then how can guys hope to compete? Nobody wants male selfies, let alone dick pics or sex tapes. These guys don’t hate whores; they yearn to be them.If Asian Americans are the new Jews, then it logically flows that Asian American men would also inherit these Jewish American male insecurities. In college, I remember once playing pong at some frat house. It was a quiet night, likely a weeknight, with audible chatter going on around the table. I overheard one of the frat guys ripping into AEPi (the Jewish frat), talking about how short and dweeby they were, in contrast to the strapping young men of his own frat. This explains why Ross pursues non-surgical rhinoplasty and weightlifting to look like “some kind of muscular Anglo or Aryan.” Looking back, I wonder what that frat bro thought of me. I probably didn’t even register.

In Hansen Shi’s The Expat, the 26-year old protagonist Michael Wang lives a comfortable, if empty and underappreciated, life as a San Francisco techie. After being overlooked for a promotion, he reaches out to Vivian, a woman who admires his coding on a dark-web-like platform called Samarkand. She connects him with her uncle, Bo, a big-time venture capitalist in China and thus begins Michael’s journey as a corporate spy for China.

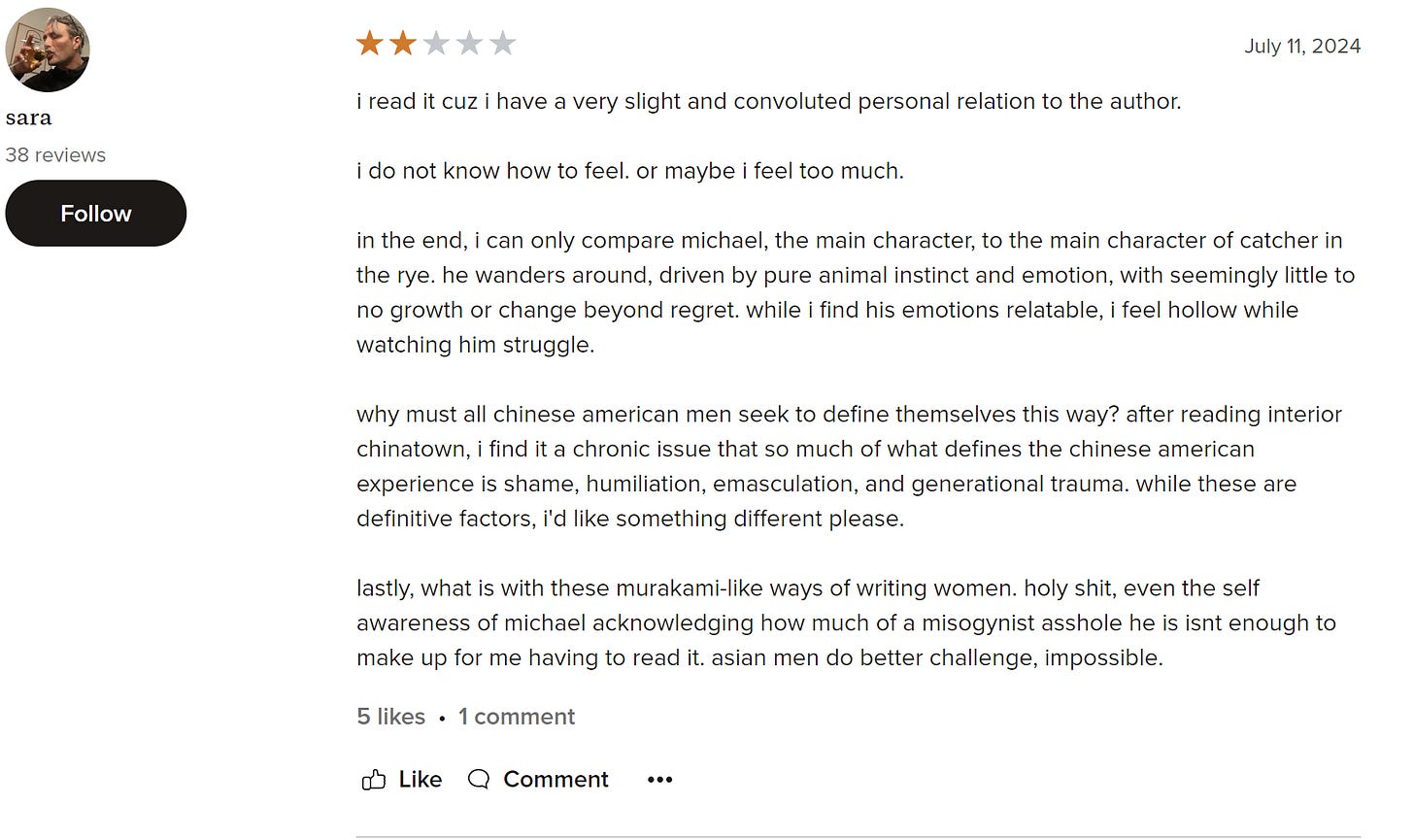

I first heard of Shi’s novel when I received an invitation to its book launch party in NYC. Unfortunately, I couldn’t make it, but the promo caught my eye because it quoted this negative Goodreads review:

I could easily sense the frustration at, and gleeful mocking of, such a review. It complains about the “chronic issue” of gripey Asian American male writing and cites Interior Chinatown as an example. But besides that, where is this overabundance? Maybe Frank Chin and Adrian Tomine, from back in the day? They might as well be Sumerians.

Michael is definitely full of gripes. He definitely knows Asian American guys are the low men on the totem pole, a humiliation that wouldn’t nearly be as bad if at least Asian American women were also similarly low in status. Misery loves company. But Michael—unlike other Asian American male characters in contemporary fiction like Lucas from New Waves2—is perceptive. From his Princeton days, he observes that “(Asian x female) seemed to unlock a hidden fast track while (Asian x male) redirected you to the spam box,” in both professional and social aspects. He and his ex-girlfriend Jessica are both from a “sexless Chinese school upbringing” in Bergen County, NJ. However, it’s only she who is accepted into a prestigious eating club (and also, gets a white lax-bro boyfriend). It’s a pattern that’s re-affirmed during a Princeton reunion, when he notes how the demographic of the exclusive Tiger Inn eating club was “primarily wrestlers and extremely extroverted Asian girls.”

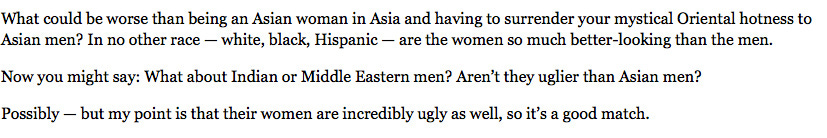

When I was a teenager, I stumbled upon the passage below. I forget where I saw it. My internet searches have been unable to find the website (thankfully, I did have this screenshot saved). I’m guessing it was some PUA blog.

Reading that didn’t make me mad. There was even a small sense of relief at just how unabashedly honest the statement was because I’d already seen its sentiments in action around me, whether through direct experience, cultural hearsay, or media depictions. Many of the observations that Michael makes (which, I assume, Shi is drawing from his own experiences) are ones that I’ve seen myself. I’m certain the vast majority of other Asian American men (and also women) have as well. In fact, probably all Americans with functioning eyes and ears have.

But what is bold to say in literary fiction is usually not so outside of that bubble. This commentary, about the different tracks of societal acceptance of Asian American men and women, has been made dating back to at least Connie Chung and the topic of the imbalance of Asian American female vs. male news anchors. For politically incorrect truthbombs, one can easily just go on social media, where it’s often done better and more comically. So why should we care that Michael makes some mundane observations unless he also has a compelling personality and internal monologue?

The botched pickup scene exemplifies this point of criticism. Early in the novel, Michael meets up at a bar with Lawrence, a college friend who’s a hotter and richer version of himself. There is a painful distinction made between a dowdy middle-class Chinese American like Michael and a sophisticated Hong Kong international like Lawrence. After giving Michael a pep talk about railroad vs. gold field chinamen, Lawrence asks Michael when was the last time he’s slept with an “American” (i.e. white) girl. Lawrence then approaches two attractive white women and eventually, the four of them end up in his luxurious apartment. Lawrence goes to his bedroom with the redhead, giving Michael a chance to hook up with the brunette. But Michael freezes up, leading the brunette to join the others. Michael goes home. Lawrence has a threesome.

Maybe Michael has some undying sexual loyalty to Asian women? But later, he expresses an admiration for Lou Pai, a former Enron executive:

I considered it criminal that the saga of Lou Pai was relegated to the status of side story, when in fact it should have been the main plot, if not the subject of its own documentary. The profound depths of this Quiet Man’s fraudulence was nearly biblical and instantly elevated him in my mind to a kind of postmodern mythical hero of Asian America. There was such a sweet spite to his brazen version of the American Dream. I relished the fact that he cheated on his own (presumably loyal, unsexy) Chinese wife with a literal stripper. Doesn’t get more American than that. . . . That night I had a strange dream. . . . [Lou Pai] invited me to his enormous ranch, “Mount Pai,” where his Caucasian stripper-wife, wearing a tight red qipao dress, welcomed us inside and served us chrysanthemum tea in blue china cups. Lou and I sat cross-legged on the floor and conversed in a fluent, native-speaker Mandarin, and he told me he was my dad.

Finally, we get a taste of some electric vindictiveness, animating some life into the body! As Gregg Popovich once said, I want some nasty! But if he thinks this, why didn’t he do anything with the brunette at Lawrence’s? That was his Lou Pai moment! I’m reminded of a line from

’s short story: “[A]s a reader I want my sociopaths to be powerful. I don't want to read about a wimp who expects to be patted on the back for not following through with his fantasies of hurting women.”3The fact that Michael does nothing in that scene isn’t really the problem. For instance, Ross is an ineffectual twit (no spoilers, but he doesn’t achieve Goldbergdom), but we see his vibrant interiority, so his character gains pungency and mass. In contrast, there’s an emptiness to Michael. What went on in his head? Did he get nervous that he was a distant consolation prize compared to Lawrence? Did he lack sexual experience and was worried about disappointing the brunette, especially if she hadn’t fucked an Asian guy before? All this would’ve been understandable and would’ve made for good reading. But instead (perhaps a victim of the show-don’t-tell mentality?), we just see Michael slink off. Another inscrutable, low-agency Asian American literary character.

But it’s not all just about sex. Michael just as eagerly seeks purpose and visibility as a more valued member of a Chinese company than at his American one. He’s haunted by his dad (about whose whereabouts he doesn’t know), who toiled away thanklessly as a computer scientist. Michael remembers how his dad cherished the cheap plastic trophies his company awarded him, how those trinkets were the only items he ever took to his travels to China. When Michael goes to technology conferences in China at Bo’s invitation, he sees men like his dad everywhere. But Bo assures Michael he can avoid their fate, because he’s young enough to fulfill his life’s great mission—to help his people and also right certain historical injustices—while still in his prime.

Going back to the Goodreads review, such sentiments reflect an attitude of You’re-not-wrong-but-just-shut-up-and-take-it. Or maybe some publication can run their usual Asian-men-feel-unwanted piece, like the NYT did recently.4 Look at the melancholy monochromatic photos of these sad Asian dudes! We just want to be loved! Doesn’t Manny Jacinto look so forlorn that you want to hug him? It’s condescending, forcing Asian American men to beg for love and acceptance.

More so than just dating concerns and body image issues (which can be solved on a personal level), what Asian American men truly abhor is a feeling of cultural irrelevance. Already alienated from our own parents and ancestral homelands, we are also to be pushed aside in our own supposed communities here? Fuck that, we say. Or want to say. So the far more respectful thing would be to not play watchdog when we try to talk about our lives and/or try to make some art out of our experiences.

Interestingly enough, that fear of cultural irrelevance—which I once thought was some cursedly uniquely Asian American guy thing—is actually becoming a universal male thing.

I do respect Shi for, relatively speaking, pushing the envelope. But that envelope has been set so far back that something like a full-running-start shoulder barge is needed. The Lou Pai passage is great, but it also commits the cardinal sin of bringing attention to a better alternative. Lou Pai is so much more of a character than Michael, so why couldn’t we have read about him instead? Instead of Lou Pai, we get a guy who thinks about Lou Pai while he’s passively moved from plot point A to B by Vivian or Bo or the FBI. I get that Michael’s supposed to be easily manipulated because he’s not nearly as smart as he thinks he is. But that doesn’t mean he has to be such a blank. Or so humourless.

Michael’s hollowness as a character is also mirrored in how weightless the story is, such as how he so frequently flits back and forth between the U.S. and China. I never got a sense of a strong grounding in either location and San Francisco might as well have been Beijing, and vice versa. One jarring sequence has Michael suddenly flying back home for Thanksgiving after receiving an alarming health-related email from his mom (which the FBI sent, which raises the question of why Michael didn’t bring up the email to his mom, which would’ve exposed the FBI’s ruse). His mom has gotten remarried to a white American man and there are some potentially dynamite Hamlet-like moments where Michael resents his mom for replacing his father with his uncle (Sam). But there is no further exploration and Michael swiftly goes back to China.

I understand it may be more difficult for Shi as a writer, though. To use Davis as a comparison, Jewish and white American male repugnance has an established and respected history. Davis is just the latest in a long line. In contrast, Shi doesn’t have many predecessors. What he does or doesn’t say about an Asian American male character has more power to shape that literary canon. I’m just speculating here, but based on my own experiences, Shi is likely dealing with the dilemma of how dark he can go without worsening stereotypes, because so many are primed to believe the worst about our demographic.

The titles themselves reveal this divide: Let Me Try Again, implying dogged persistence. On the other hand, The Expat, implying retreat and escape. For all of Ross’ hangups, he can rest assured that there will always be a Michael underneath him. Lora is even mixed-race Asian (1/4 Filipina through her father).

As I said, I liked Let Me Try Again. And for all my criticisms, I did see some bold and interesting building blocks in The Expat. Recently, I went to see the David Henry Hwang play Yellow Face and though I enjoyed it, I felt its datedness in how ideas like loyalty were debated. These days, with an increasingly vibrant East Asia and an increasingly preposterous America, many young Asian Americans—even those that don’t turn into spies—are likely to scoff at the idea of loyalty.

I hope Shi and Davis other writers like them (including myself!) of all demographics do not hold back in exploring the psyches of today’s young men going forward.5 There’s only so much we can talk about regarding the lack of male novelists and writers6; after a certain point, not much more can be said and then, there’s only the writing that’s left to be done.

Do Men Like Women Anymore? by Magdalene J. Taylor

Asian American Psycho by me

Editors Don’t Want Male Novelists by Naomi Kanakia

Incel by

is a great read that doesn’t hold back. Check out his recent appearance on the New Write podcast.

The reason he doesn't have sex with her is that he must be in some sort of mind palace zone where she's not quite the right fetish? If you're already in a cultural mindspace where your entire sexuality depends upon being particularly abject to the point where you're comparing your own ugliness to that of vast groups of ugly women, you might not want actual sex with a particular woman?

Sorry, that PUA quote really shocked me

Awesome piece as usual, though sorry to get off topic, but as a fellow fan of 'Amadeus' I feel as though it is my duty to inform you that an absolutely stunning 35mm scan of the theatrical cut has found its way online (and yes it is an authentic scan from a theatrical print, not an emulation. Enjoy!)

https://gofile.io/d/dNPd7J