Attention, Rage, and the Artist as the Supreme Being

In a world of 8 billion people, how can you hope to matter?

In recent years, multiple polls have shown that the most popular aspiration for young Americans is to become an influencer on platforms like Youtube or TikTok. This inevitably elicits groans about how today’s youth are more shallow and attention-seeking than ever before (or how America is doomed because China’s pre-schoolers all supposedly want to become nuclear scientists). But as fun as it is to sneer or fear-monger, it’s worth delving into why young Americans feel the way they do, because they can only reflect the society they live in.

Many years ago, I read a book called Fame Junkies by Jake Halpern, which looked at the various scammy talent agencies and schools that sold dreams of Hollywood stardom to wannabe child actors (and their parents). The saddest part of that book was how many of the marks were neglected children from the lower socio-economic classes. One young girl, feeling deprived of both financial and emotional support, dreamed of becoming rich and famous so that she could not only live well, but so that she could also be adored without having to reciprocate anything to her faceless admirers. It was an understandable, but also dark, power fantasy.

Collectively, we have all become that young girl. The economic stagnation and slide of the majority of Americans has been well-documented, even if nobody in power does anything about it. But just as critical has been the erosion of how much everyday people feel as if though we matter in society. The advent of robotic technology and AI has begun what is almost certainly our inevitable obsolescence in the workplace, which—in the face of declining community spaces, family life, and religion—is our primary source of feeling integral to our surroundings. What will come next? A cooler MeetUp.com? As funny as it was to see Twitter addicts cry and panic over the Elonification of X (fka Twitter), it was understandable why they dreaded losing the main community they had.

Furthermore, the interconnectivity of the world has expanded—or simply dissolved—what used to be our social borders. There is no local anymore. Everyone is a global citizen, whether they like it or not, and subject to the financial/attention economy market forces that relentlessly enforce a winner-take-all result. In this context, it makes complete sense for anyone who dreams of mattering to yearn to become an artist, the most supremely irreplaceable position in a society where everyone else is replaceable. And what are influencers if not an artists—in the broadest sense—who only have to excel in the talent of being themselves?

Judging by the actions of America’s figurative royalty, it’s clear what the most desirable jobs are. The most privileged these days no longer retire to lives of exorbitant and anonymous luxury, safely veiled from the unwashed hordes. Instead, they insist on foisting themselves on the public. Children of the White House go on to become daytime talk show hosts, Amazon Prime screenwriters, and fashion designers. Actually, forget mere figurative royalty; literal royalty like Harry and Meghan behave exactly the same way, happily foregoing Buckingham Palace for Netflix. Even the Habsburgs are doing it. The next War of Austrian Succession will be the war of which nepo baby gets to be on Succession (surely, HBO will ill-advisedly choose to make a prequel).

Why are people so riled up by nepo babies, anyway? It’s not as if we didn’t know nepotism is rife throughout our society. We all know that presidents of companies give internships and sinecures to their children, or children of friends. But when it happens in industries like fashion, literature, film, etc., we all take it extra personally, as if a core faith we had in the system has been betrayed, no matter how wisely cynical we portray ourselves as.

It’s also not just about money. A managing partner at a hedge fund giving a job to his kid in the same firm doesn’t inspire nearly same outrage as the discovery that Margaret Qualley’s mother is Andie MacDowell. And it’s obvious why. It’s telling that there’s an exclusive dating app like Raya for people in creative industries, but no such thing for, say, doctors. Even a highly compensated and respectable job doesn’t allow us to feel that if we are among the million-plus who die in a pandemic or are murdered in one of the mass shootings that happen bimonthly, we’d at least have a chance of being mourned and remembered outside of a small group of people that could all be wiped out in a single car accident. Imagine if a TikTok star was the victim of a school shooting; it’d be Gen Z’s Princess Diana moment.

A popular trope among Asian American “creatives” (I do loathe that term) is the story of having to overcome supposedly snobby and money-obsessed parents who wanted their children to go into professions like medicine, law, and tech. This is presented as a victory of art and freedom over materialism and status-obsession. But a less flattering truth that’s ignored is the class conflict here, of the more culturally affluent American-born generation seething at their parents’ dowdy and downmarket sensibilities, because the cool and rich kids rarely aspire to be coders.

A few days ago, I read a piece on Slate where a mommy influencer admitted to the perverse incentives to only focus on the negative parts of parenting, because those were the only things that received attention. The subtitle is very telling: “When I stopped wanting to complain, I realized I had nothing to write.” In The Culture We Deserve Substack, I read a piece about how how reality TV contestants were unionizing to fight back against the abuse and manipulation that their shows put them through in order to manufacture drama and insanity, because as much as the public claims to loathe messy drama queens and kings, that’s actually the only thing audiences want to watch. Another Substack I enjoy, The Intrinsic Perspective, outlined the pessimistic reality of a non-toxic social media alternative to Twitter ever thriving, because the toxicity is the whole appeal in the first place.

Also apparently, there’s also a phenomenon of women breaking up with their boyfriends because those guys didn’t like the movie Barbie. I read article about it, only to discover that the articles’ cited sources were either a single r/AITA post on Reddit or a TikTok that only had about 2000 views, which even I know is miniscule by that platform’s standards. Nevertheless, that article spawned angry Youtube videos, viral tweets, and what I’m sure was yet another iteration of online gender wars about sex and dating between people who, if they met in real life, probably would get along fine. A few weeks ago, I wrote about how social media simultaneously makes people constantly feel talked at and down to by those who probably weren’t even thinking about them.

In this environment where in order to matter, you need to get attention, and in order to get attention, you need to generate fury, what incentive is there for people to be anything but rage-mongers?

Something that’s always intrigued me is how cancel culture tends to be so focused in the culture industries (e.g. entertainment, media, and academia). At the height of #MeToo and BLM, I was more likely to read about upheavals at magazines, podcasts, university faculties, and so forth rather than the likes of hospitals, warehouses, or law firms. I would’ve thought that places like investment banks, which have a notorious reputation for being dominated by sleazy white men and their predilections, would be a hotspot for all sorts of cancellations. Maybe I’m just more attuned to cultural news than financial news, but unless it’s the SEC going through the motions (if even that) or some transparently do-nothing DEI measures, I haven’t heard of any social justice-based uprisings.

That’s because very few, except the most deluded or most viciously ambitious, view their white-collar profession as the main thing that gives their lives relevance. For most, it’s a relatively easy way to make a good living, free of the stress and dangers of strenuous manual labor. If your workplace is less than ideal, then you get revenge by cashing your fat paycheck every two weeks. Maybe you secretly watch more Youtube videos while on the clock. Who’s laughing now?

In contrast, if you’re in an industry because you need it to provide you with your life’s meaning, and you’ve also sacrificed things like stability and monetary compensation to be in it, you are more likely to demand that everything around you to reflect your own ideals. Otherwise, what is all the struggling for?

One of my favorite movies last year was Tar, which should’ve beat out Everything Everywhere All At Once in many categories, but that’s just the Oscars so who cares. For me, the two most important scenes in Tar involve famous composers and their wives. The first scene is the now infamous Juilliard scene, in which Lydia dresses down one of her students, Max—a self-identified “BIPOC pan-gender person”—after he says that Bach’s “misogynistic life” makes it hard for him to take Bach’s music seriously. When Lydia presses for an explanation, Max says, “Didn’t he sire, like, twenty kids?” Bach did indeed have exactly twenty children, showing that, at the very least, Max is a not a terrible student of music history. There are no further allegations made in the scene, and that remark stands on its own as the foundation of Max’s disdain for Bach. It’s a curious attack, devoid of any claims of rape, sexual coercion, marital abuse, child abuse, parental absenteeism, or infidelity.

But Max’s point makes more sense when combined with another critical scene, which happens soon after. Lydia and her (other) protégé and also personal assistant, Francesca, are in a car, on the way to fly back home to Berlin. Lydia and Francesca get into a friendly, though tense, disagreement about what Francesca thought was Lydia’s unfair prior characterization of Alma Mahler as having betrayed her husband, Gustav Mahler, by having an affair with Walter Gropius. Francesca asserts that Alma was justified in her actions because Gustav had insisted that she stop writing music so she could devote herself to his career.

In her essay Transgression, An Elegy, Laura Kipnis writes that “#MeToo was about a lot of things and among them was a cultural referendum on the myth of male genius.” Weinstein and his kind’s sexual crimes against women are easily understood as acts of violence and dehumanization. But if artistry, particularly great artistry, is understood as the pinnacle of humanity, and the path to achieving that glory has been denied to a gender or racial groups, that too can be viewed as violence and humanization.

The implication of the Julliard and Alma Mahler scenes is that were it not for Bach’s fertility or Gustav Mahler’s career, and the unfairness of society as a whole in favoring men like them over every other demographic, we would be celebrating the creative geniuses of Alma Mahler, Anna Magdalena Bach, and a much more diverse pantheon of great artists who—whether because of their race or gender or sexuality or other demographic characteristic—either never got to reach their full potential or have become lost to history despite their talent and production.

If art is the highest expression of humanity and the creation of art bestows the highest value to a person, then the lopsided prevalence of male artists whom we revere creates an unacceptable impression, that men are more valuable than women. When I watched Nanette, the thing that struck me was how the issue that most impassioned her seemed to be about Picasso. What he had said regarding his lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter—how he was in his prime when he was 45 and she was 17—appeared to visibly upset her the most, even in a show that delved into her personal experiences with being molested, raped, and being a victim of hate crimes. Picasso surely is not the only man who’s expressed such opinions. As of this moment, there’s a murderer’s row of raggedy old billionaires with significantly younger girlfriends and wives. Getting particularly upset at Picasso (or Renoir or Mahler or any other personally flawed but renowned male artist) only makes sense if artists are held up on a pedestal.

Even if everybody acknowledged there would’ve been a female Gustav Mahler and a BIPOC pan-gender J.S. Bach, it won’t make up for the fact that there aren’t. The bitter reality is that we will never be moved by the transcendent beauty of hypothetical artists whose gifts we’ve been denied. For the Maxes of the world, this incenses them with fury. If art is supposed to reflect an ideal sense of justice, then how can its most celebrated figures be the beneficiaries, even perpetrators, of the exact opposite? Most torturously, how can their work also be so undeniably sublime? It’d be so much easier to take if their work was clearly garbage. So the only solution is to suppress, expunge, ignore. There’s a reason that almost all of “cancel culture” is focused in creative industries, even though all sorts of terrible behavior goes on in other fields. Max and his ilk are willing to destroy birthed beauty in order to avenge abortions.

Recently, Gadsby took her anti-Picasso position to its logical conclusion and staged a whole exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, which was viciously torn apart by the New York Times. It’s an encouraging sign that Max is, in the end, just a character in a movie.

Artists, by necessity, have to be egotistical, narcissistic, and delusional to some degree. That’s not automatically an indictment of that group and its mentality. But there’s a degradation of art and artists when these things overly become vessels for people’s desire to be relevant in a world where there’s 8 billion people and more with each passing day, each of us seeming to matter less and less. Thus the desire to create art becomes indistinguishable from the desire for relevance and the desire for self-esteem, which in this era often means becoming (or aiding and abetting) a rage-monger, or a professional popular girl or boy, or becoming a proponent of affirmation art. In a sad twist, this veneration for the artist has reduced him and her into something cheaper.

I was thinking about how the publishing industry is the way it is because for one to even be part of that industry, one needs to have a degree from a selective college while only making barely any money living in a high-COL city. So it selects for people that are super passionate about what they do, so they turn to “uplifting diverse voices” to give their lives a higher purpose. It’s like being a religious zealot: the only purpose in life is to save souls. And by souls, they mean BIPOCs, who can’t exist without benevolent white benefactors.

I can tell you why kids dream of becoming influencers.

1. In today's America, what's left of the middle class is picked clean and left to dust. There are a very few out of sight rich and then there is everyone else, barely getting by. Either you get rich or be resigned to life as a peon, fighting over an ever-shrinking slice of an ever-shrinking pie.

2. Unlike, say, investment banking, sports, medicine or nuclear physics, being an influencer requires no real talent, determination, training, responsibility, or skill, other than shamelessness, self-promotion and gimmickry. Looks help, especially if you are female, but they aren't the sole criterion for influencer success.

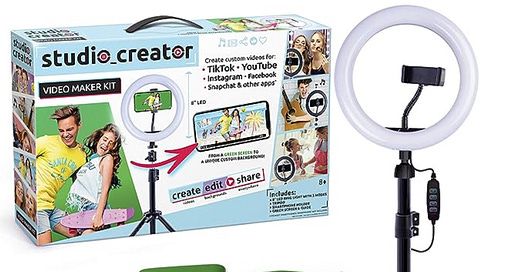

There may be other ways to achieve the goals set out in 1., but not many available to the average frustrated chump who knows what he's up against, who knows the score. You don't even need any real start up capital - any toolio can get a camera phone and start YouTubing.

In this, being an influencer is like being a rapper for those who can't even rap.