It was very early in 2020 when I first discovered the Youtube channel NewJazz. I’d just been fired again and faced yet another months-long bout of job-searching. With all the unclaimed minutes and hours I now had, why not sit down and actually try to learn what jazz piano was all about?

I first began playing jazz piano in 11th grade, mainly because my high school offered jazz band as a class and I was in full resume-padding mode for college. I did enjoy piano, having began when I was about 6. After years of lessons, recitals, and exams, I quit around when I was in 5th grade, when I got to the level where the truly dedicated left the mere hobbyists behind.

I’d taken some jazz piano lessons in preparation of my new endeavor, but unfortunately, I didn’t work that hard. I did, however, search for “jazz piano” on LimeWire and found these renditions of songs called April in Paris and Stella By Starlight, all by some guy named Bill Evans.

Bill Evans? What kind of jazz name was that? But I enjoyed these songs well enough and kept on listening. Meanwhile, I got by as best I could in jazz band. During performances, when it came time for my solos, I’d just randomly play whatever, trying my best to follow the chord changes. People seemed to like it. Sometimes, they even clapped.

The best thing I learned from NewJazz was to stop overthinking. Dominant sevenths, upper structures, rootless voicings… He first taught things in terms of hand shapes: things sound good when your left hand makes this or that hand shape. Later, the theory would explain why. But in the beginning, once that mental frustration was overcome, playing became a lot more fun. I finally read and studied my copy of The Jazz Piano Book by Mark Levine, a book I’d had since college, from cover to cover.

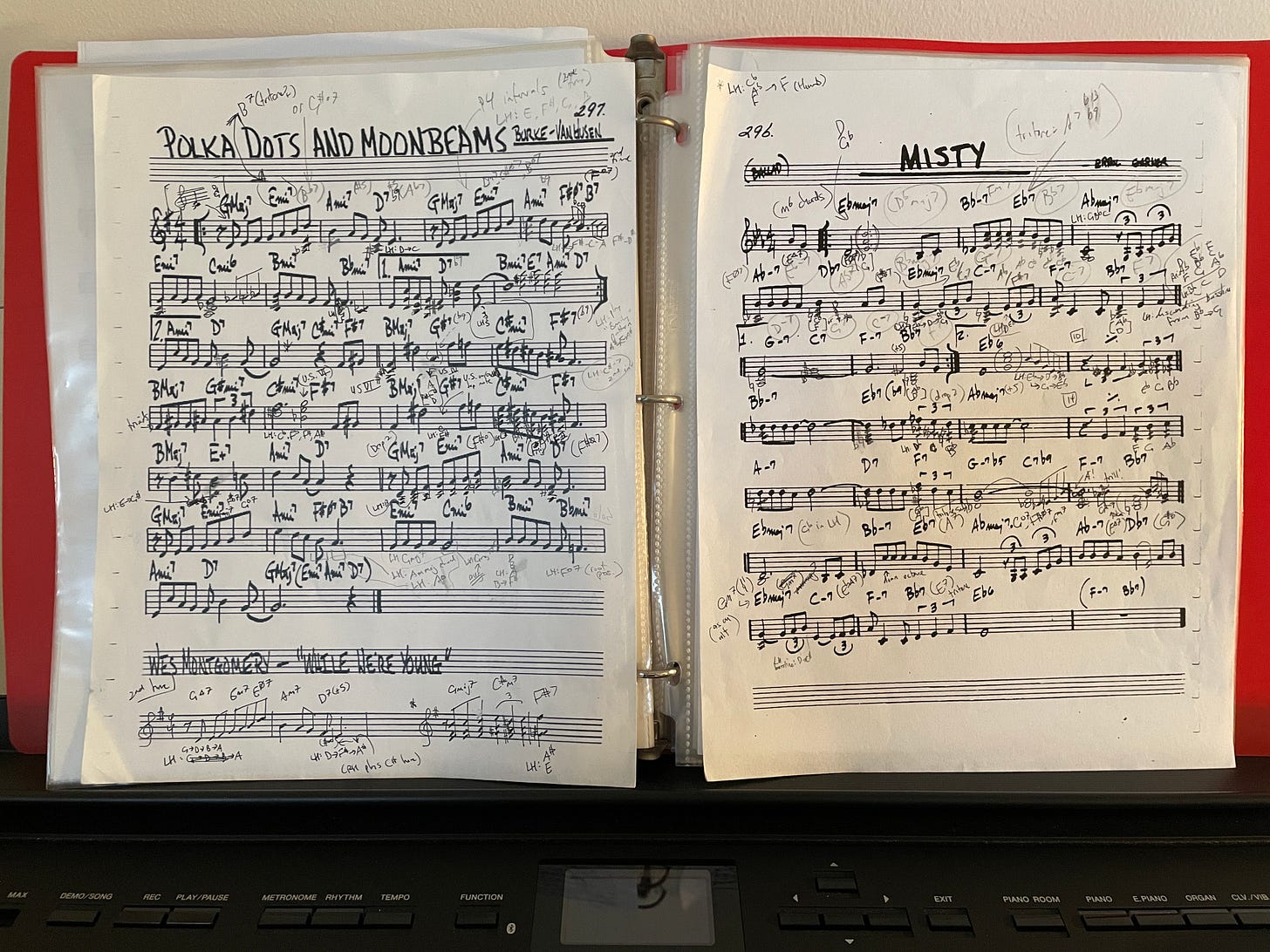

What’s so great about jazz is how few things are set in stone, so you always surprise yourself every time. Charts are more like loose suggestions than strict instructions, ready to be marked up with your own tinkerings. No rendition you play of the same song ever sounds even remotely the same. Even “wrong” notes can sound beautiful. You sometimes play something exquisite, putting together voicings and licks you didn’t even think you were capable of, only to realize afterwards that you have no idea what you just did. Oh well, that’s okay. It was for the moment. At least it happened once.

My point is not to explain how I became this incredible self-taught jazz pianist. I’m a middling novice, at best, with glaring flaws. For instance, I can’t play any fast jazz because I stick to my ballads. I rarely perform in front of others, except for my girlfriend (by happy coincidence, she has the same name as one of my favourite standards to play). I play mostly for myself, deriving satisfaction that each time I practice, I pick up a small new skill or slightly improve an existing one. That’s the best lesson that I’ve learned from piano, that with consistent practice, you will see and hear progress. Incremental, perhaps. But progress nevertheless.

I’ve read reports about how music stores and instrument makers are in deep financial crisis because young kids no longer learn music like they used to. Guitar makers like Fender and Gibson are horrifically in debt. If that’s the state of guitardom, I can’t imagine that pianos are faring much better. At least guitar players become instantly cool. With piano, you have to wait a lot longer. Nobody is swooning over Hanon exercises. Kids have often taken up music to impress others and play at being artists. Why put in years and years of effort when you can achieve the same thing by being a fake DJ and having a reliable dealer?

One of my favourite movies is An Education, where there’s a great outburst by the Carey Mulligan character, Jenny, when she’s being lectured to by her (very anti-Semitic) headmistress about potentially dropping out of secondary school:

“Studying is hard and boring! Teaching is hard and boring! So what you’re telling me is to be bored. And then bored. And then finally bored again, but this time for the rest of my life! This whole stupid country is bored! There’s no life in it or colour or fun! It’s probably just as well that the Russians are going to drop a nuclear bomb on us any day now! So my choice is to do something hard and boring? Or to marry my… JEW and go to Paris and Rome and listen to jazz and read and eat good food in nice restaurants and have fun?”

Jenny’s logic makes sense in the moment, especially since back then, even as an educated woman, her professional options would’ve been very limited. But by the end of the movie, Jenny does do the hard and boring thing of acing her exams and going to Oxford. Yet our culture seems to have taken the wrong lessons from that movie, that the takeaway is that Jenny’s riposte to her headmistress is wisdom. There’s little value placed in the hard and boring, which leads to the devaluation of skills that are honed over time.

Case in point: my friend

recently sent me this interview with Cord Jefferson, the director of American Fiction. In it, he talks about how Aziz Ansari encouraged him to pursue directing. When Jefferson said he had absolutely zero experience in the field, Ansari said to him: “All you need to do is hire people who understand the technical stuff and then be able to articulate what’s in your head.”If you take out understanding of cameras, lighting, blocking, shots, how to motivate actors, etc., then what exactly is left in directing? The almighty Vision? Then what’s everyone’s problem with AI? You just need to have the Vision, then assign all the humdrum technical stuff to ChatGPT or DALL·E.

That interview just exposed the increasing contempt that some have for actual skill or even talent. Some of my friends and I joke about how soon, the very concept of skill and talent will be deemed problematic. Where nepotism, clubbiness, and in-group ideological conformity reign supreme, skill and talent are unwelcome and unpredictable party-crashers. And who cares if no actual masterpieces get made? Few are truly in it for the art anyway. They’ll get what they really want, which are invitations to the most exclusive parties, interviews by the coolest magazines, and the chance to show up their enemies at their 10-year college reunion.

Practice makes perfect, the saying goes. But the problem is that practice doesn’t make perfect, if “perfect” is defined as accomplishing whatever your goal is. You can put in hours and hours into something and even become extremely proficient, but there’s no guarantee you’ll succeed in terms of achieving wealth and fame. If the overcoddled segments of our generation are defined by our fear of trying and failing, there’s nothing worse than trying really really hard and failing. So the path of least investment is the most picturesque one. You’re either born with the Vision or you’re not, and if you don’t instantly get 30 Under 30 recognition for it, you’re doomed.

NewJazz himself is such a refreshing counter-example to this mentality. His real name is Oliver Prehn and he lives in Denmark, working as a bus driver. In one of his videos, he talks about how he loves his day job because not only does it provide him with a living, but it’s also a simple job that allows him to dedicate himself to music when he’s not working. He says it also frees him from being tied to any musical institution and its established ways of thinking about music. May we all be so lucky to live in a country where being a bus driver is a cushy job. But that aside, it was so good to see an artist thriving in his life, unconcerned with in-crowd accolades or job titles, and instead doing whatever he could to practice and spread his passion.

Last year, I read Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings by Peter Pettinger, which is a biography of Bill Evans. Despite being one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time, Evans’ life was a difficult one. I remember a lot of chapters being about how he’d shuffle from one friend’s apartment to another in New York City or his native New Jersey. Sometimes, he’d be ranked as the #1 pianist by some prestigious jazz magazine, but crowning moments of true glory seemed few. Heroin addictions and tragedies, such as the sudden death of his bassist Scott LeFaro at 25 years old (which at least led to one of the most beautiful jazz albums of all time, Moon Beams), appeared to be more common.

I sometimes like to ask people whether they’d rather: (1) be successful and celebrated in life, but be quickly forgotten after, or (2) live and die thinking themselves a failure, but be immortalized as a great in their desired field after death. I think many, especially artistically inclined ones, would like to say they’d choose the second because we spend all our time thinking about the immortals. Me included. But do we really? I adore Evans, but reading his biography was depressing. Wouldn’t I rather have been his hack sellout peer, living luxuriously thanks to top 40 sales and fawned over by legions of fans? And Evans wasn’t even a failure in his lifetime. It’s a question worth asking ourselves from time to time, whether we’re riding a high wave in our lives or in the depths of self-doubt and jealousy.

I often hear that Learning Needs To Be Fun!

I'm not against fun, but there are times when you simply have to force yourself through untold hours of tedious drudgery before you can get to the interesting part, and there's no way to gamify it.

I hope you’re excited that you have a professional musician who holds down a day job here in America on your reading list. I love these kinds of discussions! It would be nice to see them happen on a larger industry scale, but the current culture and reality of work in many genres precludes that.

Even the “truly dedicated” burn out at a high rate if the continue into academia. My background is classical training, many kids who take up the degree don’t understand the reality of it unless they grew up with a musical background or got lessons and guidance before the degree. A lot of ‘em are just band kids who don’t know better or who want the education degree. Out of my masters cohort, only 2 have really continued playing including myself, and the other person isn’t exactly pursuing a performance career as their primary focus.

A huge problem with the devaluation of artistic skill, at least musically speaking, is that American society has largely subsumed the function of art as a means of communication into a commodity product that provides entertainment value, and most people don’t understand how the labor of music has been divided between the abstract conception of art as “The Vision” and the realities of being a working musician at that. All that music theory that has previously frustrated you can feel overwhelming because it’s function as a tool has been reversed, becoming a dictate of how to execute a style instead of the explanation of how a style is expressed (I am glad that NewJazz helped you avoid this pitfall).

But this is the problem - in the working jazz world, there ARE many things set in stone with regards to how it’s instructed. Many young cats are lied to and taught to focus on how to shred over changes because it’s easy to standardize lick vocabulary and harmonic analysis, but more challenging to instruct melody craft and communicative expression through music on a broad level. Some cultures will vibe you out if you treat changes like loose instructions, and you need to be able to know a tune (it’s changes and how to navigate them with intention) to be able to comfortably express yourself and make decisions that fit the vibe of the arrangement or call of the job on a pro level. For the sake of artistic expression, what you say is true that charts should be always be arranged and changed and evolve, but there’s a difference between a “wrong” note if you’re sticking to chord-tone soloing and a “wrong” note when you’re exploring a new way that you intend to communicate over some changes.

The reality of the working musicians in America is that there are no “middle class jobs,” and what you say of the devaluation of skill is true. You grind your gigs and hold down a day job, or you take advantage of a lucky opportunity/audition or a convenient contact and get set up in a stable institutional position or patronage system. Both require the prerequisite skill necessary to be competent on your instrument in your genre(s) (unless production alleviates that for you, which is why the barrier of entry has dropped for what can break through pop culture and streaming services), and there are plenty of people who instrumentalize music/art for the social and cultural trappings you mention instead of for its communicative and expressive power.

And unfortunately, not all day jobs are created equal. Some people get a nice time-to-labor balance, others don’t, and deciding what you focus on or sacrifice in your personal life doesn’t make the prioritizing hobby or professional entrepreneurship, let alone skill development any easier. My prospective analysis for how much easier day job opportunities will become for musicians aren’t hopeful for being balanced to the benefit of a music career, but they are plentiful, and the skills of a musician are quite adaptable to the PMC or otherwise “bullshit job” sector.

Musicians have always survived through these means, and they will always continue to do so as long as the situation of art within our socioeconomic arrangement continues as it does. FWIW, I’d rather live small and know that my musical impact persists in the hearts and minds of those who came in contact with what I have to say, and are willing to pass these memories and sentiments on to others than to burn bright and die off or worry about a legacy I’ll never experience.