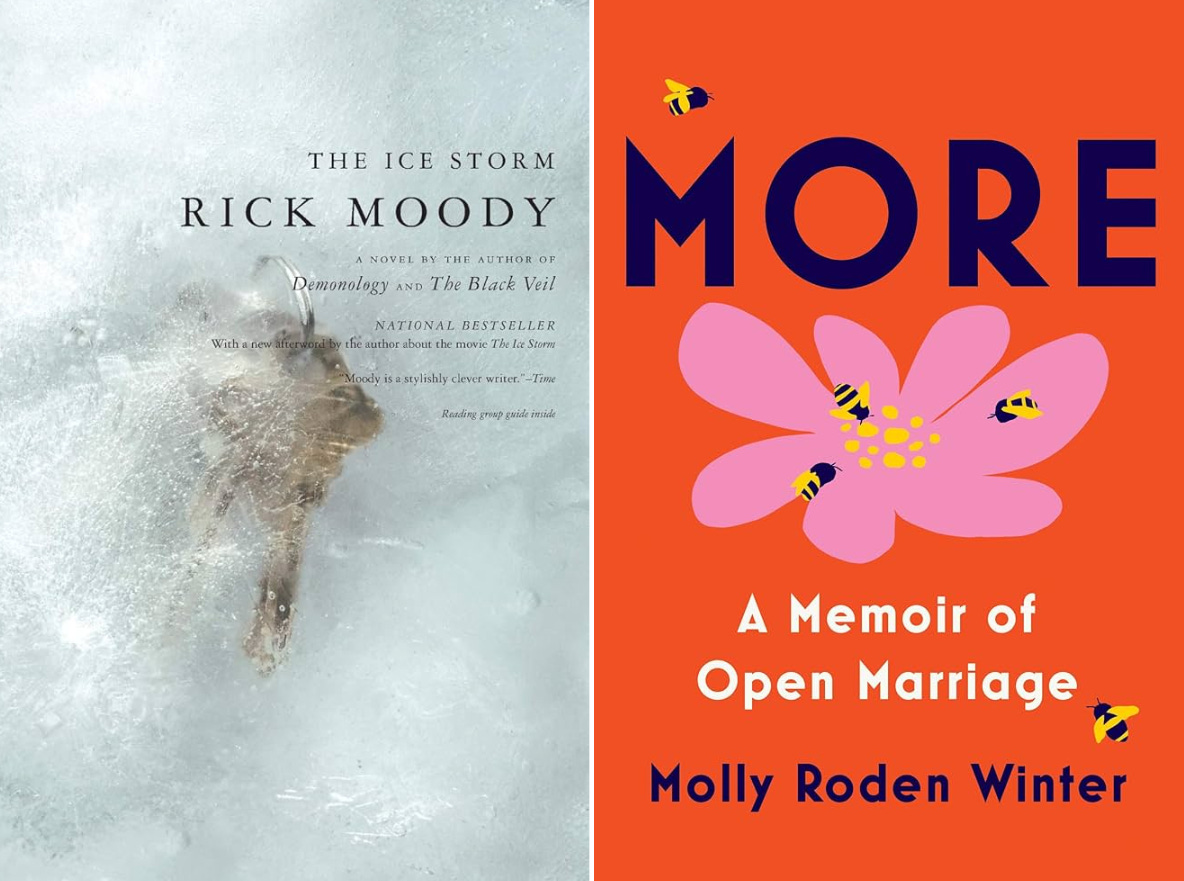

Polyamory is in the air. In the last few months on a seemingly weekly quota, the literary world has been churning out pieces on this topic, culminating in the publication of Molly Roden Winter’s memoir, More. And there’s that recent Zendaya threesome movie (that’s apparently a bit of a bait-and-switch). All this to make polyamory seem as if it’s some new, brash, and exciting thing. But it just made me think of The Ice Storm, a bestselling novel and acclaimed movie from the 90s (that’s set in the 70s).

I was too young when I first watched The Ice Storm. I must’ve picked it out at Blockbuster because it was directed by Ang Lee and I’d watched Sense and Sensibility recently, which is still one of my favourite movies. It had a who’s who of a cast (Kevin Kline, Sigourney Weaver, Christina Ricci, Elijah Wood, Joan Allen, Tobey Maguire, Katie Holmes) and great reviews all around. How was I supposed to know it was full of middle-aged swingers in horribly greasy 70s hippie-yuppie fashion and 14-year olds touching each other? Worst of all, I had to watch it all uncomfortably with my family, with the added burden that I’d picked the movie.

The movie is a faithful adaptation of the novel by Rick Moody, though it noticeably sanitizes the book’s more sordid parts. The most central character is Benjamin Hood, with the story also focusing on his wife Elena and their children, 16-year old Paul and 14-year old Wendy. Ben and Elena’s marriage has turned cold, and he’ s having an affair with his married neighbour, Janey Williams, who’s married to the very successful but also very absent Jim. Elena suspects something is going on. Also, Watergate is all over the news, but none of the New Canaan, Connecticut townsfolk want to talk about it. It’s all too depressing. So they’d rather have key parties instead.

But though I hadn’t enjoyed watching The Ice Storm, certain elements about it did stick with me throughout the years. Mainly, it was everyone’s unhappiness, which was less due to any material or familial deprivations (they all lived in big houses with assortatively mated spouses and healthy children) and more about boredom with their comfortable-yet-unexciting lives. I didn’t get a sense that the main adult characters were mourning their radical days as they rode the final stretch of the hippie-to-yuppie pipeline. Rather, they seemed more like so-called squares who’d enjoyed the more fun parts of the 60s zeitgeist, like drugs and free love, with no illusion that such things would become part of their ideological bedrock. But come parenthood and middle age, no amount of weed and swinging could bring back what tenuous grasp they had on coolness, which had been the only thing giving some pulse to their lives.

There are several notable similarities between the culture of The Ice Storm and the polyamory-discourse culture of today. They have Watergate and we have the 2024 election as the political subjects nobody wants to talk about (and depending on which circles one is in, Israel/Palestine is either also the taboo topic or the only thing anyone talks about). The New Canaanite key partiers are the exact opposite of downtrodden bohemians, just like the Park Slope polyamorists of More and its primary audience.

It can’t just be a coincidence that all this spiked interest in polyamory is just so happening as the median Millennial moves closer to middle age. The 60s had free love. The 2000s had hook-up culture. Our entire ideology was based on freedom and abundance of choice, whether it was in what we studied, the jobs we pursued, or the sexual experiences we chased. More and more of us are approaching the traditional end of that line and we may not be dealing with it well. But this is nothing new:

The idea of betrayal was in the air. The Summer of Love had migrated, in its drug-resistant strain, to the Connecticut suburbs about five years after its initial introduction. About the time America learned about the White House taping system. It was laced with some bad stuff. The commodity being traded was wives, the Janey Williamses of New Canaan. The payoff was supposed to be joy, but it was the cheapest approximation of exalted feeling. It was just a demonstration of options, nothing more. Elena felt she could judge the motives of New Canaan, Connecticut. Because she had permitted her own options to dwindle. Time sputtered and flickered and consumed the comedy of her efforts.

The bleakness in The Ice Storm is that for all the characters’ concerted attempts at debauchery, nobody is actually having fun. Before rewatching The Ice Storm, I read the novel for the first time, and if the movie is disturbing in its portrayal of affluent suburban darkness, the book is even more so. Sex and sexuality are never sexy in the movie, but that’s amplified to another level in the book. Ben and his married neighbour Janey don’t simply have passionless extramarital sex. In one instance, Ben looks for Janey in her home when she’s not there. He finds her lingerie hung up in her bathroom, he mistakenly believes she’s engaging in some hot cat-and-mouse game with him. When he realizes she really isn’t home, he jerks off into her garter belt, then hides the defiled garment in her 14-year old son Mikey’s closet, which Wendy will later find and even put on, believing it’s Mikey’s semen on it. No, that’s your dad’s jizz!

The centerpiece event of the story, the Halfords’ key party, is also devoid of any eroticism. Despite Ben and Elena’s furious tension (right before the party, she gets Ben to confess his affair), none of that translates to real sexual energy. The party itself is oddly staid, with Ben’s rival co-worker even talking business with him. Ben ends up drunkenly humiliating himself when Janey chooses the keys of another man (or rather, boy, since he’s a 19-year old there in attendance with his mother). Elena and Jim’s revenge sex against their cheating spouses ends up in tragicomedy, with Jim barely lasting a few seconds.

Yet to downplay sexual adventurism as always being merely “a demonstration of options, nothing more” reeks of condescension: the experientially wealthy exercising their sexual noblesse oblige by righting the wayward morals of the frustrated masses. I remember when I was still a virgin and reading studies about how the average American male had about 7 sexual partners in his lifetime. I thought if I could get anywhere remotely close to that number, I’d have it made. Whatever regrets I have for exceeding that goal would be dwarfed by those I’d have if I were to have remained on the other side of that aspirational number.

I love my life and I think it’s exciting. But in the big scheme of things, it’s a pretty tame one, like most people in my circle. I’ve gone to school for over half my life, and as much as I may complain about my parents, they’ve always loved, supported, and provided for me. While I’ve experienced professional tumultuousness, my job is pretty cushy and I’ve never been in danger of eviction or starvation. So dating has often provided me with some of my grandest adventures: the different types of characters I’d meet, the homes I’d get invited into, and yes, obviously, the sex. Certain parts of some neighbourhoods are vividly imbued with my recollections of specific nights, precisely because those moments were all I had with those women. I do cherish those memories.

Sex and attraction and crushes and even unrequited romance are often what make lives worth living. It’s no wonder that people who’ve been told to aspire for the best do not want to give that up, even in the context of traditional marriages. Dating apps and social media have also opened a Pandora’s Box of constantly available options like never before. How realistic is monogamy in a class and culture of easy sex, full of health-obsessed people with prolonged sex drives (whether pharmaceutically enabled or otherwise)?

As

writes, even happily married people who have spouses who make them feel attractive still feel the need for sexual validation from others. A few years ago, Ayesha Curry made some headlines when she said while her husband (Steph Curry) received all sorts of female attention, she herself didn’t experience such attention from other men, which made her insecure. Some would say it’s unwise to admit such things publicly, but looking at just the substance of such sentiments, they are so universally and terrifyingly understandable in both ourselves and others that we cover them up with outrage.That is, unless we make up proper rules of conduct to respectably contain and channel these desires. For financially and/or culturally affluent liberals who not only value living their best lives possible but also having the moral grounds to do so, polyamory is the only way forward. Otherwise, we’d have to resort to old-fashioned villainous cheating.

So that brings us to More, which does try to construct that rule-based order, but with unclear results. Some of the uproar around the book made it seem as if it were an anti-Bible for wicked wives to gleefully cheat on their cuckold husbands in the name of social progress. But I came away thinking that the book portrayed polyamory as quite a difficult endeavour, especially for women like the author. It reminded me more of a book like Nothing Personal by Nancy Jo Sales, which explores a middle-aged woman’s introduction to dating app culture, than some guided tour into a salacious unseen world.

Much of Winter’s conflict stems from her confusion as to whether her desire for an open marriage is her own or her husband’s (Stewart). Since he’s had much more sexual experience than her prior to their marriage, he’s happy for her to sleep with other men; he’s even turned on by it. So she starts seeing other men, but it isn’t just a rush of pleasure and power for her:

But what works for Stewart doesn’t work for me. It’s not Matt’s cock I want. Not really. It’s his attention. I want to imagine Matt making dinner for me. How Matt might gaze at me the first time I stand naked before him. But those things feel outside the purview of Stewart’s fantasy and therefore out of bounds.

Molly even says that in the next few years with Matt (her younger lover), they only sleep together a few times. She doesn’t have any problems attracting men, even ones who are looking for more than sex. Yet she’s not enthralled by the whole arrangement. Meanwhile, her husband gets to enjoy both their extramarital sexual encounters, which upsets her:

On the one hand, if Stew is dating lots of women, he’s unlikely to fall in love with any one of them. But on the other hand, I’m jealous of how easy it all seems for him.

Towards the end of the book, Molly asks her mother (who’d also had a husband-encouraged affair many years ago) what the source of her anger is, especially whether an open marriage made her more or less angry. Her mother answers that she doesn’t know. But one possible answer is that for many women, there is just no winning. Men’s generally higher preference for sexual variety means even devoted husbands can have no issue with sleeping around with other women; they may even enjoy the idea of their wives fucking other men. And when women try to keep up, most may realize they cannot out-men men, such as when Molly joins Ashley Madison under her pseudonym, Mercedes Invierno:

Mercedes Invierno wants to pretend that sex with multiple men is a dream come true. And Straight-A Molly is too competitive to admit that Stewart is winning the Open Marriage Games.

Yet the alternative of a traditional (closed) marriage also feels like a trap. While she is a devoted and loving mother, Molly also feels most deadened and deprived when she is defined entirely as maternal. Tellingly, one of her rules for her husband is for him not to see anyone too much younger than herself. When one of her better polyamorous partners makes a playlist for her, she revels in how youthful she feels: “I’m not a wife. I’m not a mom. I’m hardly even a grown-up.”

And when Molly’s husband asks her if she wants to close the marriage again, she laments how doing so would mean she’ll “never have the feeling of being shiny and new to someone ever again.” During couples therapy, when Molly is asked what she most wants, she says it’s for her husband to feel genuinely happy when he’s home. While she enjoys all the attention and sex from an open marriage, she finds it all too fleeting. Molly’s supreme fantasy seems to be to be in a forever honeymoon period with her husband, with the two of them eternally captured in that age together.

In its review, The New Yorker was lukewarm on More, saying that it wanted more for polyamory than Winter’s account. The review even accused Winter of co-opting the “revolution.” Our disgust at The Ice Storm is at how joyless their sex is, while our distaste for More is how lame everyone in it is. We’re still desperately hoping for someone to prove that there’s a cool and sexy solution that lets us have it all.

I once heard the phrase “sex nerds” used to describe polyamorous people. It feels like they’re taking the worst parts of stupid email jobs (Over-scheduling and constant optimization) and applying it to their sex lives. Sounds incredibly not fun!

1. A popular strain of feminist mythology aside, the principal beneficiaries of The Sexual Revolution have not been women but certain alpha males. Less the pinnacle alphas (who have always emulated feral tomcats) but the levels below that, who no longer have to even go through the motions of bourgeois propriety and can now get straight to the rutting-in-heat-in-public part.

2. Is it not written of old that, for humans at least, love is what happens after the sex has gotten boring? From what I understand, the South Asian mentality is that romantic love is more the hormones talking and that real love grows over time, a matter of shared values, shared goals and shared struggles.

From the perspective of this mindset, western obsession with romantic love is a sign of humans who refuse to grow up.