Save a Loner, Unleash a Cad

Is happiness in romantic relationships ultimately doomed to be zero-sum?

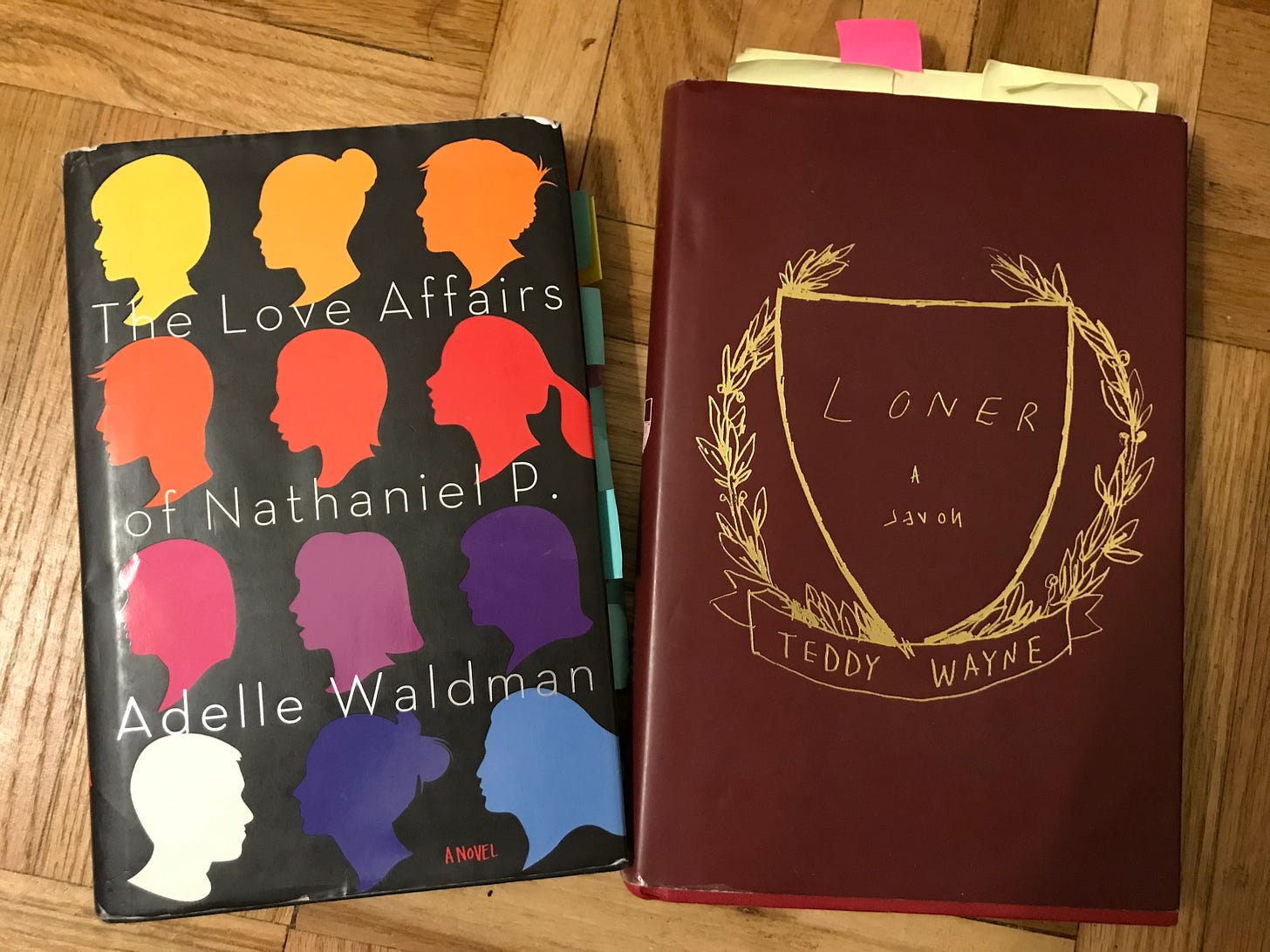

Recently, Adelle Waldman announced that she has a new novel coming out. Her The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. is one of my favorite books, one that I’ve not only re-read many times, but also one that I frequently reference, whether in conversation or in writing. In my reading experience, there aren’t many contemporary novels that delve into dating and relationships from a modern male perspective that doesn’t devolve into YA-style apologetic pandering, where you can practically see the schoolteacher standing over the shoulders of the authors, ready to rap their knuckles with a ruler for writing a no-no. When the novel was published, many expressed surprise that it had been written by a woman since the protagonist is a starkly accurate portrayal of a certain type of young(ish) man. But it made sense: most male writers (at least those seeking mainstream recognition) probably either would’ve been too image-conscious to write a character like Nathaniel Piven, or they would’ve been gate-kept out from the get-go for misogyny. Some called Waldman a (self-hating) misogynist anyway.

Love Affairs is a semi-satirical comedy of manners about the dating life of an up-and-coming young writer, Nathaniel “Nate” Piven, in the early 2010s Brooklyn literary scene. Raised in a comfortable, though not wealthy, middle-class upbringing, he attends Harvard and drifts along as a nobody, all the while harboring quiet literary ambitions. There, and for several years afterwards, he’s sexually irrelevant to most girls and women, by which he’s more confused than angered. He’s the type who’d describe himself as a 7—maybe a 7.5 on a good day. As he matures and earns some recognition as a writer towards the end of his 20s and start of his 30s, he begins to enjoy the romantic success he always thought he’d experience. “Water,” he thinks, “eventually finds its level.” The main storyline in the novel follows a semi-brief relationship between Nate and Hannah, a fellow writer, as their romance goes from sparkling to sputtering as he loses interest in her.

There is another novel, published just 3 years after Love Affairs, that provides an interesting comparison. Loner, by Teddy Wayne, is also about a bookish young man from the suburbs with strong intellectual ambitions and an uncertain understanding of how attractive he is to the opposite gender, all of which will be put to the test at, again, Harvard. However, Loner focuses solely on David Federman’s tumultuous (to say the least) freshman year, where he becomes obsessed with a beautiful and wealthy classmate, Veronica Morgan-Wells, whom he imagines has lived a lifetime of summering in “a secluded cove on a private beach, reading a Russian novel from a clothbound volume,” which is the type of upbringing that his “respectable, professional parents had deprived [him] by their conventional ambitions and absence of imagination.” And he is consumed by resentment and jealousy when she doesn’t return his affections.

Wayne himself given interviews in which he discusses Love Affairs—not to mention the facts that Waldman blurbed his novel and he’s interviewed her as well—which leads me to wonder if Loner is set in a parallel universe where Nate experienced the usual set of disappointments and reality checks that all young people—especially young men—and unraveled too easily. What makes Loner such a fascinatingly dark read is that many of David’s grievances are relatable and even spot-on. He’s right to be bitterly disillusioned by a place like Harvard that smugly purports to be progressive and intellectual, all the while cultivating social stratification on its campus because it knows that’s what it truly makes the place prestigious. And who hasn’t seen college as a prime opportunity to break out of our dowdy high school shells, or even feared that we were only accepted into a social group because it was the loser group?

Though an upgrade over my Hobart High lunch club—there were girls!—we were still clearly freshmen who had missed out on the normal high school experience and were not attempting to simulate it in college. Our dinner conversation revolved around the cuisine, the refuge of those with little in common. . . . By cruel accident, these might well become my college friends. We would choose to live together as upperclassmen, visit one another on vacations, stay in touch after graduation, attend the other members’ nuptials—maybe two of us would even get married. We would rate the hors d’oeuvres at the wedding reception and ponder what brunch would be. - Loner

I’d hate to spoil Loner, so I’ll just say that David doesn’t end up like Nate, which leads me to imagine a situation where a Nate-like character who’s come into his own in his later years is able to befriend or guide David through these emotionally turbulent times. What if Nate told David that if he simply remained patient and worked hard at his goals (besides being instantly hailed as a genius for no good reason, or dating the most popular and beautiful girl in his class), he’d eventually do pretty well for himself in all areas of life? A happy ending, right?

But for whom?

Love Affairs was somewhat controversial when it came out because of its cold and calculating examination of modern dating, at least among well-educated New York City types. Many of its most memorable passages are brutally honest, such as Nate’s guilt-ridden (but not too guilt-ridden) reflection on his dating tendencies:

Of course, these women ought to have listened when he told them he wasn’t looking for anything serious. But on a certain level, it didn’t really matter if it was stupid of them. Ethical people don’t take advantage of other people’s weakness; that’s like being a slumlord or a price gouger. And treading on weakness is exactly what dating felt like, with so many of these women—with their wide-open hopefulness, their hunger for connection and blithe assumption that men wanted it just as badly. Based on what? On whom? - The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.

Jason, one of Nate’s friends and a self-appointed teller of uncomfortable truths, says the following:

“Men and women on relationships are like men and women on orgasms, except in reverse,” Jason continued boisterously. “Women crave relationships the way men crave orgasm. Their whole being bends to its imperative. Men, in contrast, want relationships the way women want orgasm: sometimes, under the right circumstances.” - The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.

Cold comfort it must be for straight women if the Davids of our society are rehabilitated into Nates. The issue with Nate is not that he’s abusive, either physically or emotionally. He’s not a cheater. He’s even sympathetic with most feminist ideas. His main flaw as a partner is that he’s selfish and gets easily bored in a fling or relationship. His worst quality is his lack of resolve, such as when his relationship with Hannah is obviously doomed. But he’s unwilling to end it because he doesn’t want to seem like the bad guy. So he gets moody, even seemingly needling her into becoming upset so she may break things off first. Above all else, his happiness and comfort are what matter most.

But from his point of view, why should those women’s romantic happiness be his top priority when his happiness wasn’t theirs in years past? When he was 25 and desperately lonely, “everywhere he turned he saw a woman who already had, or else didn’t want, a boyfriend,” or they would “cheat frequently (which occasionally worked in his favor).” Others were “taking breaks from men to give women or celibacy a try” or “too busy applying to grad school, or planning yearlong trips to Indian ashrams, or touring the country with their all-girl rock bands.” But then Nate turns 30, and he notices that the same women, “[n]o matter what they claimed, they seemed, in practice, to care about little except relationships.” Nate occasionally stews resentfully with such chiding, but for the most part, he’s not too bothered because he knows that ultimately, the balance of power is now in his favor. Both Hannah and Aurit (Nate’s best friend) explicitly tell him so, that it’s deeply unfair that men like Nate can choose to settle down when they feel like, and usually be able to find a woman, sometimes significantly younger, to do that with, which now looks like a prelude to the many online wars today about age gap relationships that don’t involve outright pedophilia.

In a progressive metropolitan American culture where traditional obligations like raising a family are set aside, or sometimes outright mocked, what should be the motivation for a man to settle down, outside of his inherent desire to do so? Aurit even assigns moral and political failings to men who aren’t eager for committed relationships, but if what makes one a feminist vs a misogynist—besides clearly serious issues like abortion rights and prosecuting sexual assault—comes down to which gender deserves to be happier in dating and relationships, the outlook is bleak because of the many unfortunately zero-sum aspects of happiness, especially in romance. Boys have their problems too. Who knows how true internet reports are, but I’ve heard of teenage boys becoming enraptured by Andrew Tate because they feel like eternal losers. But they’re 16; they’re supposed to be incels.

Is there a way out of this? Young marriage has many problems, but it did center around a basic mutual exchange. Since women generally enjoy a social peak in their younger years compared to men, she has to give that up if she marries young. At the same time, while men’s social peak happens later, a man who marries young must give that up in return. But without young marriage, why shouldn’t women want to maximize freedom during their most socially and sexually powerful years, and then demand commitment from men right before the power dynamic flips? Conversely, why shouldn’t men try to prolong our own best years for as long as possible, knowing that aging is not as socially cruel to us, and our fertility window is bigger than women’s?

The fact that men can act like this must be a major source of resentment for women. It certainly would be for me if I were a woman. Some will argue that in the end, it all evens out. But even if you accept this as true, women must feel shortchanged that their so-called best years happen when they are more naïve and inexperienced, when they’re most liable to squander those years and make regrettable decisions. If youth feels wasted on the young, for women, it must seem doubly true.

There’s also a tragedy to living with the knowledge of what you’ve lost. It reminds me of a philosophical question I read about in college, in which a question was posed: if time is infinite, then all the time we’ve spent being unborn would be infinite as well, meaning that even if death was forever, we’ve already known it was like to not be alive for eternity. So isn’t it completely irrational to fear death, an experience we’ve all had? The philosopher, whose name I don’t remember, said no, because once you know what it’s like to be alive, not living is more painful than if you’d never known it. So not only do women live longer on average than men, but a greater proportion of their lives are spent past their so-called best years. Longevity must feel more like a curse than a blessing.

Getting married young surely works for some people, but it probably won’t for most. It’s questionable whether it even worked in the past, with only the illegalization or stigma of divorce providing a cover of contentment and stability. Yet it’s also clear that women and men’s lives operate on a cycle that’s out of sync, one that’s off by only about a factor of 5-10 years but is still critical enough to be the cause of a lot of the gender wars today. There must be some level of frustration that social and technological progress has not bridged this divide, and even made things worse. It’s not surprising that there are new iterations of feminism that advocate for a return to some forms of more traditional dating and attitudes towards sex. But that’s an essay for another day.

Probably you've heard of the growing strain of British feminism that has become explicitly reactionary about gender roles and sex.

You may have seen this in the Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/06/reactionary-feminism-differences-between-sexes/674447/

One of the feminists covered in that piece was recently interviewed by Bryan Caplan: https://betonit.substack.com/p/my-louise-perry-interview

I'm sympathetic to people who feel ill-served by our present hypercommodified and hyperliberated sexual culture, as I hardly feel entirely at home in it myself. But I'm even more strongly inclined than you to suspect that traditional social models appeal to us more from a distance and were likely just as dysfunctional as our own when experienced up close. As with everything else - people, ideologies, places - with culture we tend to notice the flaws in close proximity and idealize the remote. I've encountered enough first-hand observation and accounts from men and women thoroughly immiserated by the traditional models to cast a skeptical eye on any appeals to the grass being greener.

At the end of the day there may just be no escaping the necessary/difficult individual negotiations/compromises necessary to build an effective mutually fulfilling partnerships. We're only human.

I loved Love Affairs. I did feel though like Nate just is gonna end up marrying the influencer girl (not really an influencer but would be one today) and not feeling particularly happy about it. Which is to say, if the Nates of the world were deliriously self actualized, that would be one thing. They want to go back and time and heal the childhood self that never got love, but they can't ever do that unless they trust and respect the woman they're with. In Nates case he can't be with women he respects, like the doctor or the newspaper reporter, because he is still playing out some nerdboy insecurities, whereas the doctor and the newspaper reporter will eventually find the right guy and be happy, he probably won't be.