Searching for the Perfect Friend Group

Literary Brat Packs, Lost Generations, and all the groups we wished we were in

I don’t have a lot of long-time friends. Or rather, the people I’m closest to are those I’ve met somewhat recently, like in the last 5ish years. I can’t quite decide if that’s a good or bad thing. On one hand, time and memories are the most irreplaceable elements, and you only have one chance to make them with others. You could meet a kindred spirit or even soul mate tomorrow, and no matter how close you become, your shared history will only begin then, and not a moment before.

On the other hand, history can also be a burden, even a cage. How many of us revert to our childhood selves when we’re with our parents, their mere presence changing our personalities? We’re not static beings, or at least we should hope we’re not. There is a tendency to romanticize our younger selves as less crafted and more genuine. But it’s often the exact opposite. So what good are shared memories if that past traps us into remaining characters whose skins we’ve happily shed?

Almost all of my 20s was spent in places where I was never going to stay for long. And I’ve only been the place where I was born and raised twice in the last 15 years because I no longer have any family there. That probably explains why my closest friends are not childhood friends, or high school friends, or college/law school friends, or anybody I met in between all that. So of course, every few years, I form a new group of friends. Or is that covering for some other unflattering reason for this pattern of behavior?

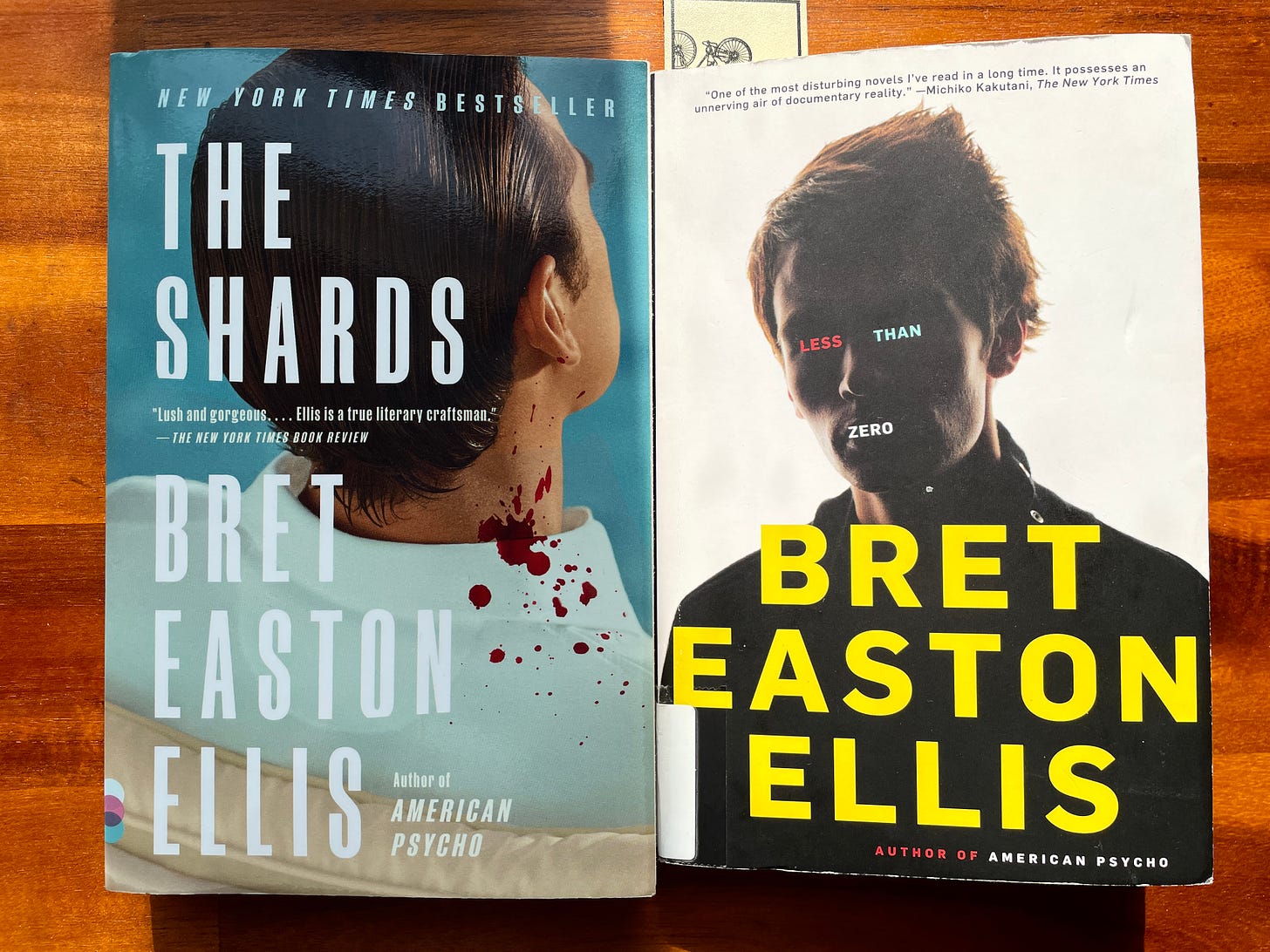

It’s fascinating to read Bret Easton Ellis’ The Shards and Less Than Zero together. The former is his latest novel, published in 2023, while the latter is his first-ever published work. Both share many similarities, such as wealthy teenaged male protagonists who run in popular party circles, a 1980s Los Angeles setting, and copious amounts of drug use that induce more apathy than euphoria in its user. Both Bret and Clay (the main characters of The Shards and Less Than Zero, respectively) sleep with guys, though Clay is more bisexual while Bret is trying to hide his homosexuality. They both have beautiful and rich girlfriends with barely closeted movie mogul fathers in sham marriages.

I liked The Shards the most out of any of Ellis’ novels, though that’s not exactly fulsome praise because I’ve never truly liked his other fiction like American Psycho and The Rules of Attraction. I’m more of a fan of his writing philosophy, especially as I’ve gotten older, which explains why I liked White—his non-fiction book about his thoughts on culture—more than his novels. Compared to Less Than Zero, The Shards is the more dramatic novel, a pseudo-memoir involving a sadistic serial killer named The Trawler. Yet I found the story much more grounded, with its past-tense elegiac prose more inviting than Less Than Zero’s choppy and frenetic present-tense narrative.

Despite the chill of disappointment I felt about Ryan leaving the Schaffers’ earlier I can now attest that Sunday in September was one of the last nights, if not the last night, I was ever fully happy and there was no fear.

vs.

Take an orange from the refrigerator and peel it as I walk upstairs. I eat the orange before I get into the shower and realize I don’t have time for the weights. Then I go into my room and turn on MTV really loud and cut myself another line and then drive to meet my father for lunch.

Regrettably, I usually don’t even read more than one novel by a writer whose works I love. So why have I read four novels by a writer whose creative writings I admittedly haven’t even really enjoyed all that much?

The protagonist in The Shards is named Bret Easton Ellis, which is not surprising since Ellis (the real-life writer) has become just as much a character as his literary creations, second only to Patrick Bateman as a fixture in our cultural imagination. There is something that draws us to him and makes him relevant today, even though he acknowledges in White that he peaked as a writer with American Psycho, which was published when was 27.

I sort of knew about how his time at Bennington College, which overlapped with Donna Tartt and Jonathan Lethem’s years there, was a once-in-a-lifetime convergence of generational talents. As I read through The Shards and its often autobiographical accounts of how the protagonist/author lounged around in the most luxurious mansions while dating the most beautiful girls and writing drafts of what would be the first novel in a glittering literary career, I realized that Ellis, at essentially every point in his life, was at the center of some enviable innermost circle.

I then listened to the Once Upon A Time In Bennington podcast because it is Ellis’s time at Bennington that most piques my curiosity. More so than his hedonistic high school days, and more so than his even more hedonistic 1980s Literary Brat Pack era. It made me think of how much I’d once looked forward to college, where I thought I’d undoubtedly find that circle of friends I’d always wanted. Not necessarily consisting entirely of writers, because that’d be too vocationally incestuous. Rather, a group filled with a creative energy, with a disdain for complacency. With a fervent, even arrogant, self-belief in its own exceptionalness. We’d never debase ourselves to gossip about others. Because we were the ones who’d be talked about.

But it didn’t work out that way. Partly because of my own self-doubt that must’ve emanated from me like a rotting stink. To be fair, though, weren’t those doubts fully justified? I hadn’t written anything of substance, much less gotten any recognition from it. All around me were people who were seemingly far more talented and experienced and harder working. Why even try, since I was already approaching the decrepit age of 22, about to be spit out back into the real world, having squandered my best chance to play furious catchup?

Still, there was a nagging thought, that even if I had the confidence to assert my place among artistic elites, invitations into such coveted circles were jealousy held and only given if you met a minimum threshold of: (i) talent, (ii) money + connections, and/or (iii) sex appeal. Like a Bret Easton Ellis or a Donna Tartt. Or a Walter Kirn fucking his way into the experimental theatre group at Princeton. Meanwhile, I was only really even remotely eligible for (i), and unfortunately, I was no incandescent genius.

Many years ago, back in Philly, I was hanging out with a college friend and we played that game where you name the girls or guys you wished you could’ve gotten with in college. As we went back and forth, bandying about names of girls, we noticed that while everyone he named had been in our social circle, many of mine weren’t. Like an upperclassman I’d briefly known doing a play together. Some girl in a completely different group that I’d found a way to get to know. He said he envied how much I’d branched out during college.

Social adventurousness is the flattering way to interpret that tendency. But of course, a much less rosy take is that it’s social climbing. A restless angst caused by my belief that I ought to be in some better place, a better crowd. Or maybe not “better,” but just “different,” because I’m always evolving. But evolving towards what and for what reason? And if it hasn’t happened by now, will it ever?

I’m luckier than most, though, in that after all this time, I have found a group of talented, thoughtful, and like-minded writers over the years, mainly through the internet. But we all live far away from each other. Though I talk with some of them almost every day, I’m lucky if I see them in person once a year. Maybe twice at most. And we’ve never all hung out as a group. And it may never happen. And it’s too late to live our most formative years as our own pack, not just writing together but also drinking and fucking up and fucking around together.

Still, I should be thankful for at least that. I’ve tried many times to find writing circles. The best one was the MeetUp group I joined in my one post-law-school year in Philly. We met every first Sunday at a church in Old City. Even though I initially feared that everyone there would think my story about college was boring or juvenile because everyone there was significantly older than I was, I learned that even total strangers with no vested interest in protecting my feelings could like my writing. It was a monumental first.

Subsequent ventures weren’t as great. Upon moving to NYC, I took a writing class with an writer I really liked, and while the class was good, my attempts to stay in touch with my classmates afterwards failed. One MeetUp writing group I joined was a scam, with me and some other poor sap having to sit awkwardly for an hour in some noisy Brooklyn café as the organizer tried to sell her classes to us. A couple of years ago, fresh off my first publishing credit, I tried organizing a local writing group. While I got a lot of enthusiastic responses, in the end, only two guys showed up. One was more interested in the scene than actually writing. The other actually wrote, but I hated his writing (or at least the one story he shared). We only met up that one time.

In The Party’s Over,

said that “a particular dream of media careers as a scene, as a social club, is fading and dying.” I love that piece, and that quote may or may not be correct. However, my past weekend was chock full of readings, which really are parties interrupted by people reading off their phones for a few (hopefully single-digit) minutes. Maybe they’re nothing compared to the heyday of NYC media, but what do I know? I’ve got nothing to compare it to. What the hell was I doing during the good old days? A couple of weeks ago, a friend I met during my law school internship visited me in NYC. I told him the worst thing about law school wasn’t that I felt it was soul-crushing or miserable, but rather, I didn’t feel much about it at all. He completely agreed.We all dream of finding our own Lost Generation. I don’t even know that much about them. Maybe they all secretly hated each other and it’s all a marketing gimmick for the Gatsby Party Industrial Complex. Like how the Literary Brat Pack was a marketing gimmick and Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney have said they never actually really hung out as a group.

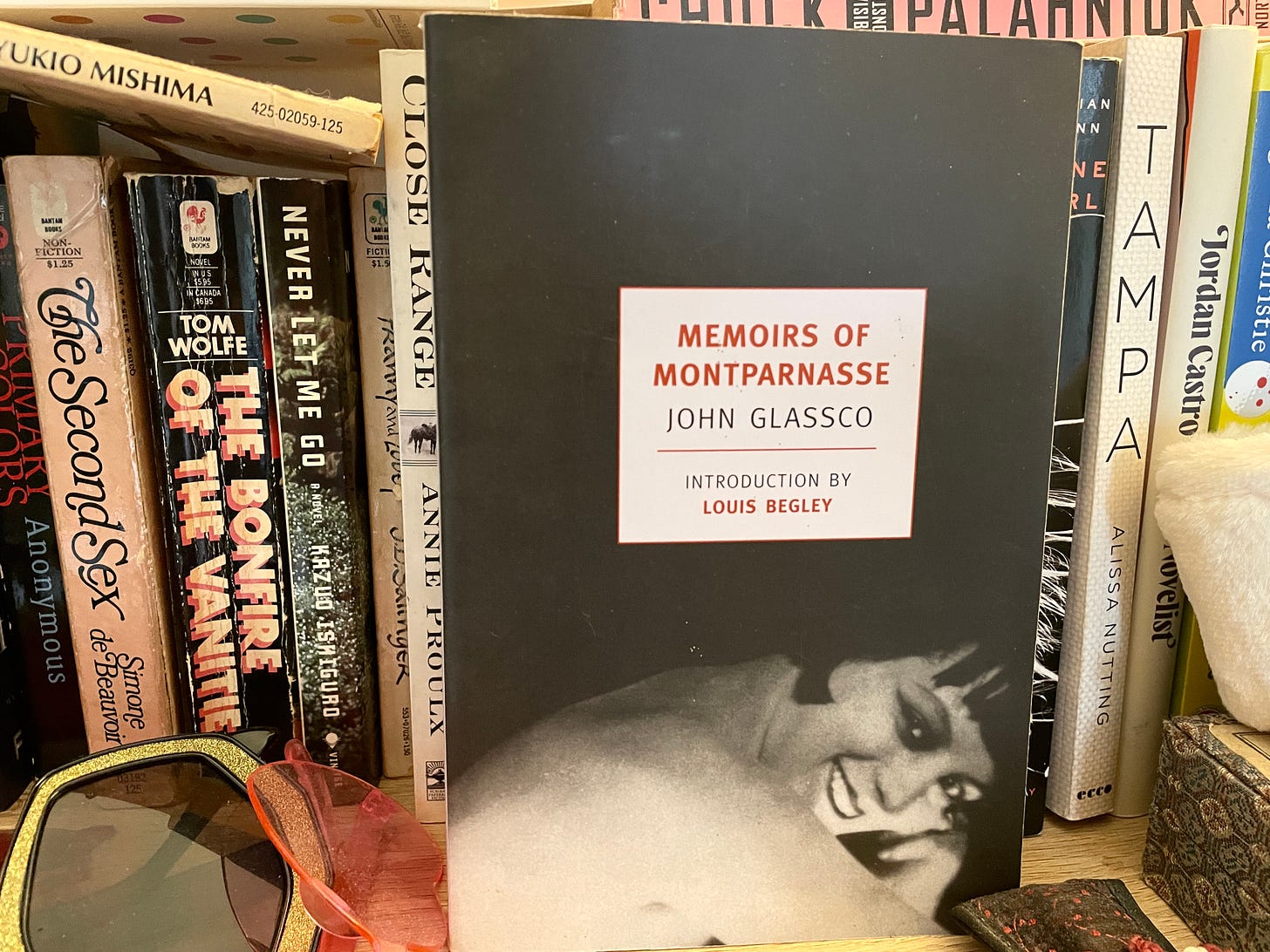

But fake or not, we’re still entranced by the idea of finding such a group and being in it. Some of us just will it into existence, like John Glassco with Memoirs of Montparnasse. That book’s mostly bullshit, right? Still, it’s an entertaining read, a fantasy of how some kid from Montreal can just hop on a boat and travel to Paris to hang out with Hemingway, Stein & Co. for a little bit. It’s funny that I like that book since I hate Midnight In Paris so much.

I’ve been in NYC for 7.5 years now. I’ve met a lot of good people here, but I’ve also noticed that my cycle has started up again, sometime back in summer of 2022, as I’ve been drifting away from the people whom I met here and have been my close friends for the past few years. Some things can’t be helped. People move away. People get married. People have children. People develop new passions and interests and lose old ones that once bound you together. So the search continues.

The grisly murders aside, Bret in the The Shards looks like he lives quite the aspirational life for a high schooler. He’s rich, popular, handsome, has access to powerful people who can further his dream career (though that comes at a steep cost), and has so many worldly experiences that by the time he gets to college, he’ll be a man among boys. In real life, one of the reasons Lethem resented Ellis so much at Bennington was because from day one, Ellis seemed a fully actualized man and writer, ready to embody the literary zeitgeist with himself at the center. In contrast, Lethem was a lower-middle-class kid from (then uncool) Brooklyn who was still trying to find his place, not the Ray Ban-wearing LA kid whose dad definitely earned $40 million commissions from selling buildings.

Yet for all this, Less Than Zero, which takes place after The Shards in pure chronology, is all about how Clay returns to his hometown after just a semester of college and realizes he’s forever alienated from the crowd he grew up with. And even someone like Easton Ellis, who was always at the center of it all, still ends up as, to quote the Bennington podcast host, a “spent cultural force.”

I had a call recently with another college friend of mine, someone whom I’ve surprisingly become closer with after graduation. He works in music and I’ve always imagined his youthful days were at least somewhat Ellis-like. But even he expressed similar feelings of alienation as I have, of feeling as if you’re alone on a little boat as you try to sail towards your dreams. It didn’t exactly make me feel good, but it did give me some perspective, that the search is lonely for all of us. It’s still worth a shot, though. What else are you going to do in the meantime?

If there's any comfort, I think enduring work generally doesn't spring out of environments like this. Aside from Ellis, none of the "Brat Pack" writers are discussed or even thought about much thirty years on—when was the last time you cracked open Tama Janowitz, Jill Eisenstadt, Mark Lindquist, or frankly even Jay McInerney? Donna Tartt wasn't published until years later, and the same with Jonathan Lethem (who dropped out of Bennington).

When you look at other famous literary circles, the numbers are even worse. I've never read anything by any member of the Algonquin Round Table except Dorothy Parker; same with the Bloomsbury Group beyond Virginia Woolf. I'm sure they enjoyed their parties, but a solid work ethic seems like a more likely contributor to literary longevity.

A few years ago, I guess more than a "few", it was prepandemic, I actively tried to form a writers' group, recruiting through Ok Cupid. We actually met once, there were 4 or 5 of us, to get to know each other, at a café. It didn't get beyond that. The platform was chosen experimentally as the means, but I guess there's a metaphor to extend here. It's a bit like dating. You need to find persons who are both "into the scene" and whose writing you appreciate, and who appreciate yours. Or at least the potential thereof, or the attitude. But it's harder than dating, the drive to write being less urgent than the one for more basic companionship, and being a group it's as complicated as polyamory.

It has seemed to me, too, that groups do good to the artistic endeavours of their members, literary and otherwise. Beside the Brat Pack (I confess Less Than Zero has been long on my list but no more than that), Oulipo and the Bloomsbury Group come to mind. But I think their vitality came not from each being an extraordinary creator on one's own, but from being a passionate audience, a reader, to each other. Which is why the "coveted circles" and "perfect friend group" you allude to seem a fata morgana to me, and the triad of talent, money+connections and beauty unnecessary.

The 13th chapter of John William's wonderful Stoner begins thus, and continues the theme:

> In his extreme youth Stoner had thought of love as an absolute state of being to which, if one were lucky, one might find access; in his maturity he had decided it was the heaven of a false religion, toward which one ought to gaze with an amused disbelief, a gently familiar contempt, and an embarrassed nostalgia. Now in his middle age he began to know that it was neither a state of grace nor an illusion; he saw it as a human act of becoming, a condition that was invented and modified moment by moment and day by day, by the will and the intelligence and the heart.

When you have passionate peers, you make your own scene. Whatever it is: basketball, grunge music, poetry, some video game. Gwern's The Melancholy of Subculture Society is apropos https://gwern.net/subculture . If you do what you do with ambition and not just to pass the time, surely you'd get better, and if you do so for a while, you'd even get very good. If you do it out of respect, dare we say love, to each other, you don't even need talent, you'd figure how to do it with time and persistence. It's great if you can get paid to do what you love, but until then, you could make do with the time you have left when you're done with work.

Connection is important, but I think connection to such peers is more important than a connection to the past, i.e. the establishment. Of course, if you're some son of, people would pay attention before you've even done anything. I'm not sure it's so enviable. Many sons and daughters of didn't fare so well in life, and perhaps when you are forty you'd be grateful nobody knows about the novels you wrote in your twenties. It elicits indignation when a less than mediocre piece of work gets much acclaim (I was thinking about one such today), but as Augusto Monterroso said, posterity always does justice, and anyway there are greater injustices in the world and we would meet greater personal misfortunes in our lifetime. For a while the group of nobodies stands on the stage alone, their own sole audience. if they take their activity seriously, divert each other's attention from other distractions, then eventually, amen, they will create something that would fascinate the outside world. Let the impresarios come searching for you in the alleys when you have something rather than kowtow at their doors when you don't.