The Baby Burden

The value of children, but only as abstract concepts and as other people's problem

This week, I was thinking about maybe writing about Freddie deBoer’s new book, How the Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement. Or maybe about Eric Rohmer since I just watched The Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle this past week. Or a vigorous defense of Lost in Translation after I saw some social media grumblings about how racist the movie is, which are complaints that are sure to get louder with Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla about to come out in a month. But I can write about those things later. Right now, why not write about the latest celebrity gossip instead?

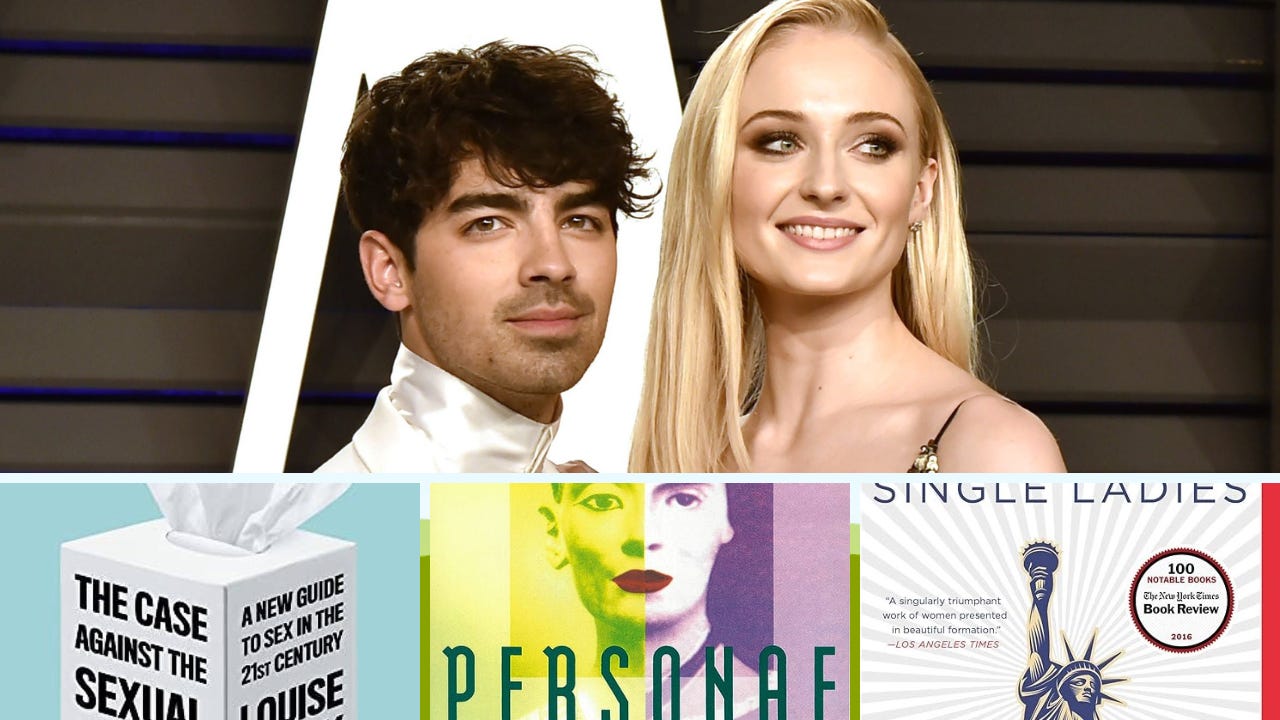

Celebrity gossip can be very useful as proxy fights for bigger issues, especially in this time of affirmation art that turns entertainers into our moral avatars. The thing that I find most interesting about the Joe Jonas/Sophie Turner divorce story is how the topic of children brings out such anger and resentment in people. There are those who lament Turner’s lost youth for having become a young mother. Others seethe at Jonas’s opportunistic photo ops with his children. But there was no sense that these children were a blessing. Instead, they were only discussed as if they were deadweight or props.

It brought to mind the online brawls over a recent TikTok in which a 29-year old woman talked about the nice Saturdays she could have since she didn’t have any children. This incensed a lot of people, especially conservative men (and, I’m sure, conservative women), about how this woman was idiotically foregoing the rewards and duty of motherhood for frivolous things like Beyonce and shakshuka. But I’m not sure how many of her attackers even actually like kids that much. Were all those angry men disappointed would-be fathers who genuinely believed that, if not for women like that TikTokker, they’d be happily living the Seventh Heaven life? I doubt it. They want women to want children, because somebody’s got to.

These incidents highlight the growing societal tension between two irreconcilable facts: (1) children are the future, and (2) contemporary culture, despite its odes to parenthood, doesn’t bestow much social value to being a parent. The reasons for (2) are somewhat due to economics, with stagnant wages and rising costs of living acting as major obstacles for prospective parents. But if most young people of reasonable child-having age suddenly came upon both money and security, they’d suddenly start having children. In The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, Louise Perry writes that “[i]f you value freedom above all else, then you must reject motherhood, since this is a state of being that limits a woman’s freedom in almost every possible way—not only during pregnancy but also for the rest of her life.” Fatherhood is not nearly as physically or culturally demanding as motherhood, but it has the same directional effect.

Governments all around the world are having in raising their respective countries’ birthrates despite all sorts of generous pro-natalist policies. Because economics is only one part of the issue; the other parts are social and cultural values. If your society glorifies individual professional achievement, luxurious living, and youthful sex appeal, then children are nothing but destroyers of all that. Instead of being respected as aspirational figures, parents are instead looked upon with pity, even dread, as those who’ve now been shunted off to irrelevance. Except maybe if they become mommy bloggers, which in the attention economy, is the only social currency that having children can provide.

If having children is indeed a threat to the most aspirational lifestyle in one’s society, then the fact that women bear most of the biological cost of it must seem like a curse, akin to an entire sex being born with a hereditary disease. In Sexual Personae, Camille Paglia compares a fetus, in both wanted and unwanted pregnancies, to a “benign tumor” and a “vampire.” She further describes how even for for women that do not want children, their monthly period is a reminder that regardless of their personal desires, their bodies ultimately are an obstacle for them to overcome to achieve their dreams: “Western woman is in an antagonistic relation to her own body: for her, biologic normalcy is suffering, and health an illness.”

There are many reasons that the trans movement has become the latest and most heated front in the culture wars, but I’ve long had a feeling that one significant component was the desire among straight cishet women to believe in the high mutability of not only gender, but also biological sex, in order to completely sever the ties between womanhood and childbearing. Because who wants to be defined by a biological burden, a harbinger of unhappiness and dashed dreams? Perhaps one day, that unwanted obligation could even be offloaded to men. Would that be the ultimate dream?

Fury at this unfairness is why I think the likes of Rebecca Traister and many women of her political and cultural mindset were so skeptical not only of marriage, but of monogamy as well. In All The Single Ladies, Traister bristles at the thought of heterosexual female sexual desire as characterized within a traditionalist framework, where even short-term flings are seen as women ultimately auditioning male suitors for long-term commitment. To highlight critics of hook-up culture, she chooses social conservatives and “very concerned elders.” She also quotes writer Hanna Rosin, who likes an overbearing boyfriend for a young woman to an unwarranted pregnancy. For Traister, straight female disdain for committed monogamy is imbued with a “spirit of conquest.”

This puts her in direct opposition with Perry, who lambasts the Sexual Revolution as having been a boon for a few men at the expense of most women. To Perry, the movement just represents little more than the triumph of the playboy. Characterizing men as more sociosexual than women (i.e. preferring to have many sexual partners to having few), her argument is that a truly feminist world would compel men to conform their behavior to suit women’s preferences, not vice versa.

When it comes to sex, Perry is right in that most women can’t out-men men. But the underlying logic of Traister’s beliefs makes sense too, because if long-term commitment, marriage, and children are what prevent the citizens of a metropolitan progressive culture from living the best and most enviable lives, then the gender that apparently wants commitment more is necessarily going to be in the weaker bargaining position.

As someone who feels stifled by the idea of marriage in my mid-30s, I can certainly understand why a woman would feel even more so when she often has to confront that issue at a younger age. So it makes sense why Traister would want to simply disavow committed monogamy altogether, lest it tip one’s hand at wanting that big loser thing of marriage.

Traister also writes of female selfishness as a virtue, as an “enlightened corrective to centuries of self-sacrifice.” Society has, for quite a while, already established male selfishness a la Adam Smith or Gordon Gekko as not only a personal virtue, but also a necessary civilizational element. If Perry is right in that motherhood—and parenthood in general—is the antithesis of freedom, and our society equates freedom with happiness, then the two aforementioned irreconcilable facts will continue to be estranged. Are iWombs truly the last, best solution?

One of my good female friends is currently struggling with the inner conflict of being both an independent, educated, feminist, career oriented, self love and self care fixated, fun seeking, cosmopolitan woman and... a new mother of a 1 year old. She loves her kid but her resentment of her *situation* burns red hot.

She has an involved partner who makes high six figures and tries his best to share the burden of child care. They spend thousands a month and spare no expense on supplementary help, nannies etc, and she still laments and mourns the death of her freedom; the loss of her formerly independent self. Coming to terms with how motherhood has narrowed and constrained the possibilities of her life has been very disturbing to her, and she copes by seeking out examples of women in the media who seem to have managed to keep their personal dreams and goals alive (artistically, educationally, professionally) despite having kids.

The complaints about the unfairness of it all is the connecting thread - contempt for the biological and social role that has forced her to subsume her own interests, in what she still feels is the prime of her life.

In fairness to her, the pregnancy was unplanned and she never had a strong desire to have kids and be a mom as a core identity. It's something she wanted in the abstract, but she also didn't realize how much of her former self/life, which she liked a lot, she'd have to sacrifice.

I think women like her feel this sense of injustice more because of the optionality of their former lives. Materially and culturally, she had an incredible amount of youthful personal freedom for about 15 years, which suddenly plummeted to almost zero. Of course such a drastic change would be a shock. This in contrast to women who for cultural and economic reasons have long internalized expectations of motherhood, and actually desire that social role as the defining aspect of their identity.

For women like my friend, Motherhood is not only a huge burden and responsibility, but also a huge sacrifice - one for which they think they deserve all manner of compensation and privileges from their spouse and society under the rubric of equity and egalitarianism. Views

like "motherhood is it's own reward" or "it's nature, suck it up", have obvious non-egalitarian premises and implications that crash head first into core liberal progressive ideology.

Reading this, I wonder if this is essentially the crux of western feminism; the feelings of injustice and unfairness at having been born with a uterus, desiring emotional connection more than sex, and seemingly wanting kids more than men.

I think a lot about how much resentment white women have toward men, and my feeling has always been that white women desire to become white men. And white women feel "oppressed" because they cant escape their bodies.

I actually wonder if wealthy women who want children simply wont make use of poor surrogates. Or if motherhood wont be pushed onto poorer women so wealthy women can be mothers without the burden of motherhood.

I also think of women who wanted to get themselves sterilized or tubes tied but faced opposition from doctors out of concern they might want kids one day. Even though they decidedly did not, hence the desire to remove childbearing capabilities.

I wonder a lot about what will happen. I read a post on Free Press' substack today about how men are opting out of dating because the criteria of what women want from men is too high and most men cant measure up.