Who's the Next Lena Dunham?

To brutally but lovingly capture a segment of American youth culture

A couple of weekends ago, my plans took me to Williamsburg not once but twice, which was a bit unusual because it’s not a neighborhood I’ve ever spent that much time in. What little experience I have with it is second-hand, hearing stories of it when it was hipster heaven/hell in the 2000s (when the word “hipster” meant something) or in the 2010s when the techies, lawyers, and brand managers moved in (and the hipster had emerged triumphant). Looking around me, it was hard to believe that this was once a place that inspired such love and loathing, the epicenter of a certain type of American youth culture.

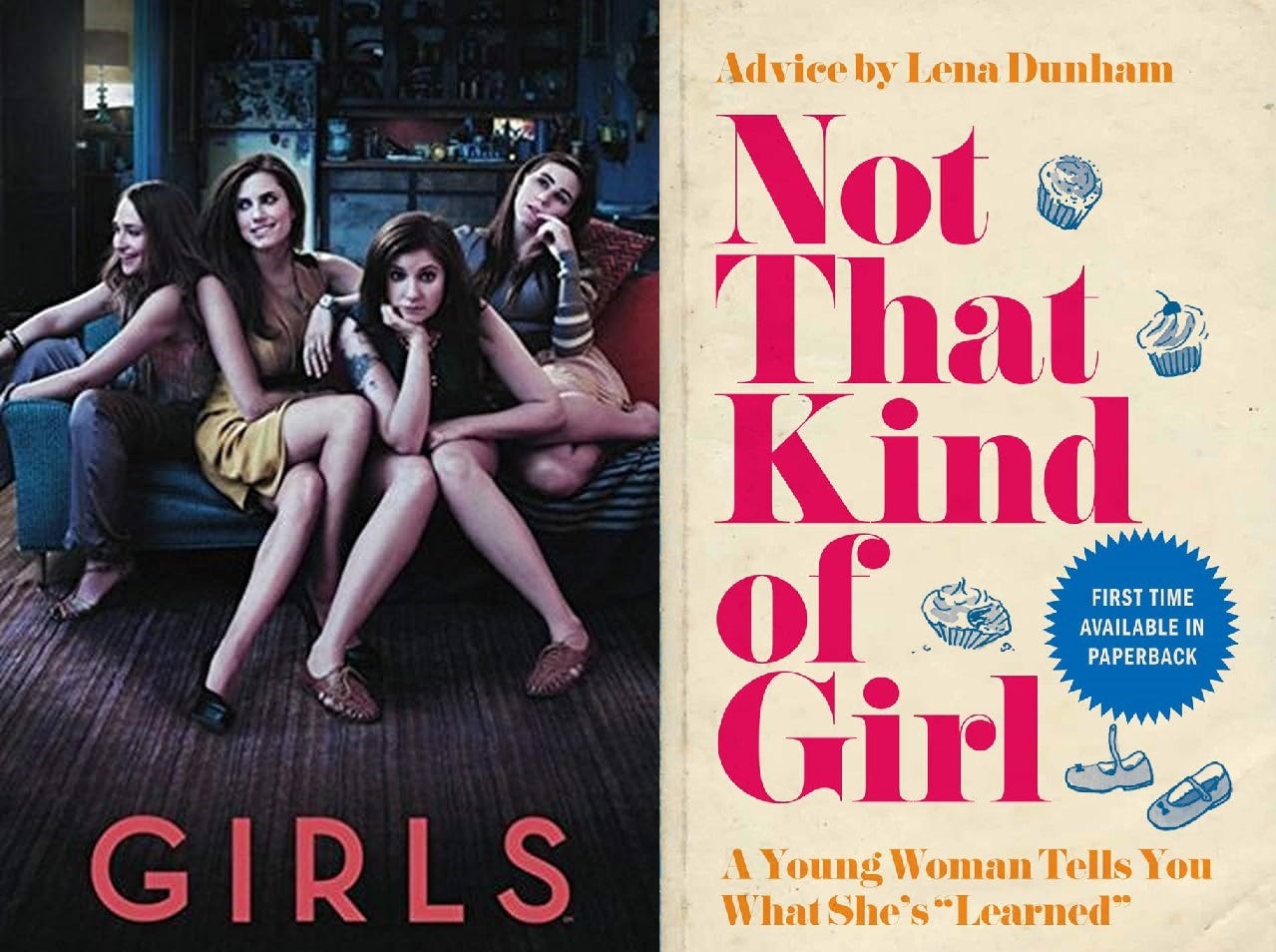

Coincidentally or not, at around this time, my podcast app recommended me a show called Stargirl, in which the host Emma Baker delves into the symbolism, appeal, and controversies of a certain type of famous young woman (e.g. Emily Ratajkowski, Sally Rooney, Caroline Calloway). One of the episodes was on Lena Dunham, and me being the Girls devotee that I am, I had to listen to it (yes, I am aware Girls is set just a bit north of Williamsburg in Greenpoint). It was a good listen, and it made me read her essay collection, Not That Kind of Girl, which I’d never even thought of reading despite the fact I’ve fully (re)-watched through Girls at least 6-7 times by now.

I enjoyed the read, though the first half was definitely better than the second. One of the more fun parts was seeing which snippets from which essay made it into the show. The online so-called boyfriend who died! The baby clothing shop! “I hate it when you leave!”

The most illuminating part was finally seeing for myself the part that has caused Dunham so much grief over the years. It’s in the essay Who Moved My Uterus? in which she recalls looking into her 1-year old sister’s vagina and screaming after discovering that her sister had shoved marbles up there. People accused Dunham of being a molester, but little kids do all sorts of weird and gross things before concepts like proper boundaries are understood. To be honest, I’d always thought that Dunham had put those marbles into her sister. So after reading the actual text, my reaction was, ‘That was it?!’

I’d always felt there was an agenda-driven vendetta against Dunham, largely borne of jealousy. Some of the most pointed attacks on her from the start was about the lack of diversity in the show. And for the first couple of years, I bought into it too. I knew of people like Hannah, Marnie, Jessa, and Shoshanna in college, and I certainly wasn’t so fond of them that I’d want to watch a whole show cinematizing their lives. Still, the race-based criticism made me suspicious. Even back then, I knew that when POC in culture industries cried “diversity,” what they really wanted was for everything to remain white, except to slot themselves in as the protagonist in lieu of the white lead. Besides, if you read between the lines, Girls did have quite a few insightful things to say about race, especially about Asians.

The most fair criticism I’ve heard of Girls has come from my friend Trevor, who believes that Dunham, under the guise of self-critique, is actually sneering at the plebeian wannabes like Hannah and Marnie who come from nice middle-class families in Ohio and New Jersey and want to make it as culture-class somebodies in New York City. Dunham, though not the daughter of world-famous celebrities, still grew up in Tribeca lofts, went to fancy Brooklyn private schools, and learned to schmooze from an early age with art dealers and wealthy patrons. It’s a line of criticism I haven’t heard elsewhere, and it’s worth considering. In her book, Dunham talks about an early web-series she made with her friends in their post-college malaise, The Delusional Downtown Divas. It’s proto-Girls in that it’s self-mockingly hilarious, except with characters who are closer to Dunham’s own biography as NYC-raised art scene kids. Perhaps making Hannah a transplant was a way to make her character more relatable. Plus, Jessa fulfills the role of moneyed insider in the culture class, and given that she’s the least sympathetic character of the four protagonists, I don’t think Dunham was acting as snooty gatekeeper.

I honestly don’t remember if I began watching Girls as a hate-watch, but pretty early on, I realized that I’d been wrong to preemptively dislike the show and to have believed it was all an exercise in aspirational self-glorification. The show was, in fact, the exact opposite, and unlike all of its contemporary peers, it was made with an uncomfortably critical eye turned on itself, which is one of the artistic qualities I most admire in an artist and his/her works. The show’s also incredibly funny in a natural and understated way, and with each re-watch, I swear I’m still finding little jokes that I missed before.

Much has been said and written about how selfish, spoiled, self-destructive, and lacking in self-awareness the main characters are. But crucially, they’re not portrayed so in a caricature-like way absolves the viewers from identifying with those flawed characters. If entertainment is like a mirror, then instead of being a flatteringly curved one, Girls is flatly spotless with harsh fluorescent lighting hanging right overhead.

Years ago, I wrote a takedown of Master of None, a show that I was ready to love after all I’d heard about how well it portrayed the children-of-immigrants experience. But even before Trump ruined Obama-ism, the show rang false from the get-go as a smugly purest distillation of Older Millennial metropolitan utopia, where having a pleasingly diverse band of friends that’s wittily cognizant of social issues and know to order a cortado at the buzziest café means staking a claim in the ascendant progressive future. Even if it weren’t for Aziz Ansari’s babe.net incident, the show would’ve aged horribly and become embarrassingly outdated by now (if anything, Ansari should be grateful that the claw incident has at least given him some cancel-culture edge).

It was the exact opposite reaction I have whenever I watch Girls. Due to its prescient skepticism of its own milieu, Girls will be eternally fresh, aging beautifully like a well-maintained leather jacket. Despite Dunham being an infamous Hillary fangirl, her artistic instincts weren’t subordinated to her political interests, and her show consistently reveals the shallowness of Obama era liberal culture. A prime example is when Hannah first learns that her ex-boyfriend, Elijah, is gay. She reacts to this discovery with the usual platitudes about being happy for Elijah for living his truth or whatever.

Hannah: So I’m processing this. Does this mean that the whole time we were together, you were…?

Elijah: Are you asking did I always want to have sex with men? Yes. Are you asking did I think about it while we were together? Yes.

Hannah: So how were you able to have sex with me?

Elijah: Well, there’s a handsomeness to you.

Hannah: Oh my god.

Elijah: Oh maybe that wasn’t the right, um…

— Girls S1E3: All Adventurous Women Do

But soon enough, their exchange turns snippy, then nasty, because more than her purported political ideals, Hannah cares about being desired. Now that Elijah has destroyed that, she goes after his “fruity little voice.” In the end, no matter how high-minded we try to be, all we really want is to be liked and loved.

The perfect bookend to all this comes a few episodes later, when we see a college flashback of when Marnie first met Charlie. In the exchange above, Hannah claims that had Elijah been “this gay” in college, she would’ve known. Though she later concedes to Marnie that Elijah did seem gay in college, it’s not until this flashback that we see the full extent of just how deluded Hannah must’ve been back then: Elijah suddenly appears, with the exact same voice and mannerisms as he has post-coming-out, complimenting Hannah on having done her make-up the way he’d recommended, then shouting out his love for Scissor Sisters.

Each season of Girls is great in its own way (though season 4 is least so), but my favorite is season 3 because it deals most directly with Hannah’s fragile identity as a writer (not to mention Shosh’s incredible outburst at the beach house). I freely admit I see a lot of myself in Hannah (we were even born in the same year), and when she stupidly quits her cushy job at GQ, I could understand her thinking, which I wrote about to a friend in 2014. She is initially ecstatic about finally landing a proper writers’ job, only for Ray to gleefully deduce that it must be a lower-tier job as a sponsored content writer. Still, she’s enamored at first with the steady paycheck, actual benefits, and in particular, free snacks at the office. But this is also when Adam and Marnie start realizing their own artistic dreams, with Adam getting cast in a Broadway show and Marnie beginning her music career with Desi (whose weaponized male-feminist crying will never not make me laugh). Suddenly, Hannah is no longer the creative one in her social circle, and since she doesn’t actually do a lot of writing at this point, her image and job title are all that she has to confirm that, yes, she is indeed a writer. Of course, she could actually buckle down and start writing, but writing is a very lonely endeavor, and the whole reason Hannah wanted to be a writer in the first place (as she tells Chuck Palmer in season 6) was to feel less lonely.

It’s a common insecurity among a lot of writers, I assume: you’re not that charming, smart, attractive, athletic, or any other qualities that bestow worth on an individual in your surroundings. So if you could jujitsu your otherwise annoying neurosis into literary gold, perhaps then people will like you. Maybe even love you. And because so much of yourself is riding on this lone ability, you're petrified of finding out that you can't actually do it that well. So rather than stick it out in a relatively comfortable office job with a bunch of demoralized (former) writers and write in her free time, Hannah does one of the few things she’s good at: quitting her job in a fit. At least working at Ray’s coffee shop will allow her to feel soothingly unformed and still full of potential, as opposed to an office setting that announces to the world that her dreams are dead and dumb.

Marnie’s a favorite of mine, too. She’s easily the funniest character, though not intentionally on her part. My friend Jane wrote an interesting piece on Marnie, We Love To See A Pretty Girl Losing. Marnie is indeed the big loser at the end, isn’t she? Shoshanna is the clear winner with her dream career, the handsome fiance, and upgraded set of new friends. Hannah has her job in academia and a baby. Jessa has Adam, which might count for something. Marnie has the Michaels Sisters.

But for all her cringe, there’s a tragedy to Marnie. She’s beautiful, but not captivating enough to really coast through life on her looks as Jessa does. She’s too corporate for art circles, but too artsy for white-collardom. She’s what Hannah might’ve been if Hannah looked more like Brooke Shields. But Hannah’s blessing was that she wasn’t, so from an early age, she knew she had to hone her writing. With the other three protagonists, there is a sense of finality to that certain phase of their lives. But with Marnie, it’s more as if it’s just beginning.

Girls first aired over a decade ago and it’s common nowadays to see glowing retrospectives, even mea culpas from those who are sorry they’d judged the show and everyone involved so harshly. It’s easier to do so now than back then since the Hannahs have aged to reveal that their once seemingly forever potential that so threatened us does indeed have limits. Thomas-John, who was portrayed as a Williamsburg interloper in season 1, is now probably the median resident there. And the things that so annoyed people about Hannah & Co.—“do what you love” culture, cupcakes, text messaging—now seem quaint, and the critics have moved on to being irritated about other behaviors, words, and ideas.

Which leads me to ask, who’s the next Lena Dunham? By that, I mean someone who can capture a specific set of youth culture and portray/examine it with minimal flattery? Enough time has passed that there should be a distinct youth culture from the Obama-era gentrifying Brooklyn environment that Girls beautifully captured like a Nikon F3, one that goes beyond simply switching up which social media is most used and abused. I’ve seen snippets of this winking self-parody in movies like Last Night in Soho and Bodies Bodies Bodies, but not enough to sustain a multi-season TV show.

Would a new Girls even be allowed? A recent i-D piece noted how poorly received the most recent iterations of Sex and the City and Gossip Girl were due to their “neutered, politically correct tone.” We live in a much more overtly political age than a decade ago. For all the political flak it received, Girls avoids directly talking about politics, with the most notable exception being Hannah’s brief fling with a black Republican played by Donald Glover (not coincidentally, that was an extremely forgettable arc). The show instead expressed politics through its characters’ personal relationships and actions, which was more reflective of a time when politics didn’t become such a visible identity marker like it did in the Trump era. But the Trump era (disregarding the very real prospect of his return to the White House) is also done with, and hopefully that means less didactic art.

The next-generation Girls also can’t just be a direct sequel, or a similar concept but twice as much!! Girls was often compared to SATC as a generational successor, and though I’ve never watched SATC, I do know that Girls is nothing like it except for some superficial similarities like four main female characters who are all friends. SATC was much more aspirational, with many people today, whether they admit it or not, wanting those characters’ lifestyles. I can’t think of any sane person who wants to be a Hannah, Marnie, Jessa, or Shosh (actually, maybe some do want to be Shosh and it wouldn’t be the craziest thing). Whereas SATC lumbers on with movies and extended TV shows, Girls ends with the fracturing of the foursome. The ending of the series’ penultimate episode is simultaneously cathartic, sad, and funny as you’re grateful that the group can finally be honest with themselves, but you also mourn the times they’ll no longer have together.

But that doesn’t mean the show has ended! The twisted genius of Girls is that in its unsentimental capturing of an admittedly irritating cultural era, it has lovingly preserved it as a time capsule that can be looked at again and again. When I first watched it, I was close to Hannah’s age. Now, I’m Old Man Ray. At some point, I’ll be Jasper’s age and I’ll still be re-watching it. In the meantime, I eagerly await its successor, and if anyone wants to go into deep dives into Girls with me, drop me a line. A few years ago, when a friend of mine learned I was a big fan of the show, she congratulated me, as if I was the first guy she’d ever met who’d said that. Girls is the best, most honest, and most accurate Millennial art about Millennials that I’ve ever experienced, and for that, even if she does nothing else of note, Dunham will always have my admiration.

This is a very scary essay because when I read it I had the distinct impression that maybe Lena Dunham is actually talented? And so I had to give myself a refresher of why Lena Dunham is a clueless out-of-touch Caucasoid, so I googled the time she and her friends recorded a video of them lip synching to "Formation" to encourage people to vote for Hillary Clinton. EXCEPT IT TURNS OUT I RASHOMONNED MYSELF AND LENA DUNHAM DIDN'T DO THAT! IT WAS AMY SCHUMER ALL ALONG! My god, was I hating the wrong woman all this time? And even worse - what if Amy Schumer is also talented? I mean, this is a post-"Who's the Next Lena Dunham?" world. For all we know she's great too!!

In conclusion, if you write an essay about Hannah Gadsby my brain will implode.

I liked this post a lot. I was in a fiction mfa from 2012-2024 and my classmates were achingly jealous of Dunham, though it didn't make sense because they were all from regular non privileged backgrounds so how could they have ever ended up like her?

I don't think there's anything malicious in making Hannah middle class. It's a common tool for upper class writers. Look at Emma clines protag in the girls. Cline is the scion of a vineyard owner, but her character lives in a tract home. Same for Curtis sittenfeld in prep, she is the daughter of a judge and all her siblings went to Princeton or some shit, but her character is middle class. It's just a way of being relatable to a middle class audience and dramatizing the outsiderdom that you feel emotionally. Kind of like how in Heian japan, most of the writers were actually public figures, priestesses or royal consorts, with ceremonial roles in public life, but they only wrote about cloistered, domestic women--folks of a slightly lower social class--becahse that was their audience. Girls at its peak only had like 800k viewers. Imagine if it had been even LESS relatable. Not that stuff about rich folks doesn't succeed, but it has to be aspirational. Nobody wants to see rich, whining Hannah. But middle class Hannah is achingly human