Yellowface-saving

Publishing loves to be criticized, so long as those criticisms are of absolutely no threat

Generally speaking, the target of your withering criticism shouldn’t enjoy it or praise you for it. Perhaps somewhere down the road, the recipient will admit that it was what he or she needed. But if the reception is too enthusiastically received, that’s a good sign that the critique either wasn’t that hard-hitting or that the one making it was never taken seriously.

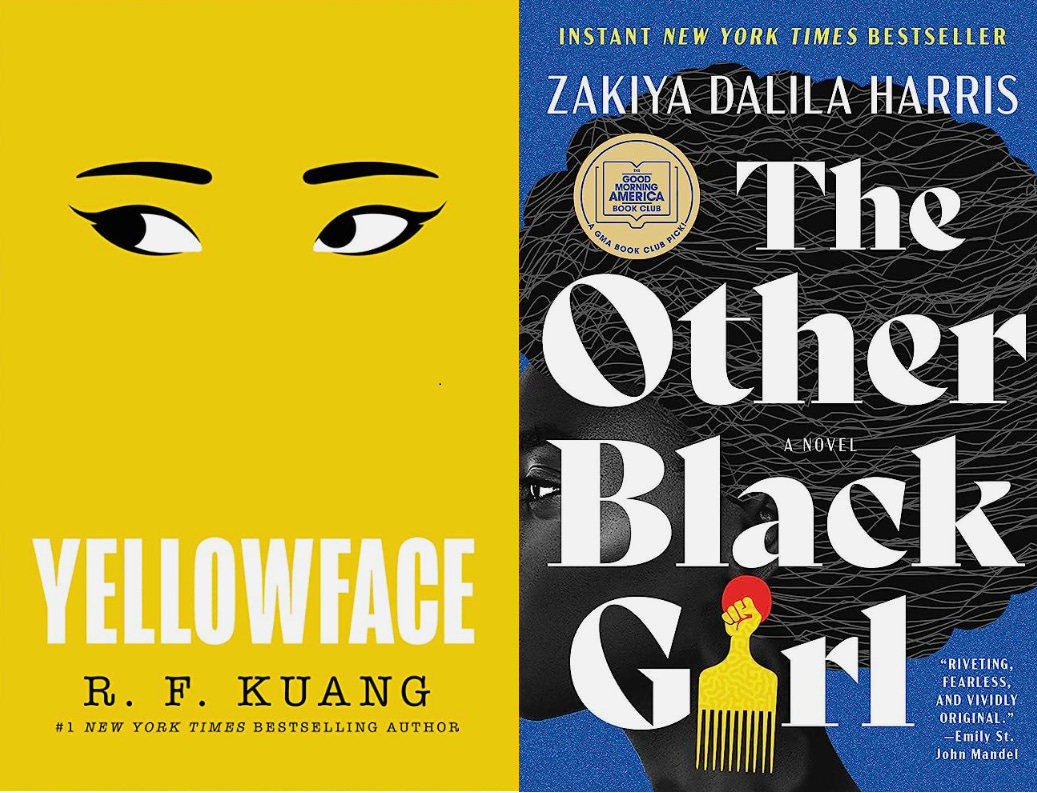

Both Yellowface by R.F. Kuang and The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris have been praised by elite cultural gatekeepers like the New York Times as bold and much-needed critiques of the publishing industry, especially on issues of race and diversity, by women of colour. About TOBG, the NYT’s headline read “Her Book Doesn’t Go Easy on Publishing. Publishers Ate It Up.” The article also describes how the book sold for more than $1 million at auction and how even before publication, Hulu had hired Rashida Jones to write the TV series. Interviewed agents and editors talk about how special the manuscript is and how they just had to have it, no matter the cost. Similarly, just a couple of years later, the NYT ran a near-identical headline about Yellowface: “She Wrote a Blistering Satire About Publishing. The Publishing Industry Loves It.” Even though the article describes Yellowface as “brutally satiriz[ing]” the publishing industry, it also notes that “[j]udging from the largely ecstatic early responses to the novel, the literary world seems to enjoy being skewered.” In a Salon interview, Kuang talks about how she “felt like [her] editors were just egging [her] on and encouraging to make the book even more transparent and more vicious and more pointed about the realities of the industry.”

So it would appear that publishing is unusually and admirably thick-skinned, self-critical, and gracious. Perhaps even a little masochistic. But that would be assuming that both these novels pose any credible challenges to the existing order.

TOBG is about Nella Rogers, a 20-something black woman who works in a prestigious NYC publishing house. She lives the typical microaggression’ed life one would expect a minority woman to live in such an environment, which is why she’s so ecstatic when her company hires Hazel, a young black woman, as a new fellow editorial assistant. But Nella starts suspecting Hazel of subtly undermining, sabotaging her, and even leaving threatening notes that tell her to quit. Eventually, Nella uncovers a conspiracy involving mind-controlling hair cream that brainwashes black women into becoming Other Black Girls that acquiesce to the racist status quo.

The protagonist of Yellowface is Juniper “June” Song Hayward, a young white female novelist with a sputtering career who has the curse of being close friends with Athena Liu, one of the most spectacularly talented and gorgeous writers of her generation. When Athena suddenly dies in an accident, June steals her late friend’s unfinished manuscript about Chinese laborers in World War I and passes it off as her original work. Rebranding herself Juniper Song, she attempts to ride the identity politics wave until people realize she’s not Asian and her plagiarism scheme is uncovered. Terry Nguyen has written a great review for the Cleveland Review of Books that’s worth checking out.

To understand why Yellowface and TOBG have been so readily accepted by the very people they apparently take down, it’s because these novels aren’t so much revolutionary satires as they are intra-elite gossip, with the predetermined rule that nobody in the established club will actually lose their positions. Some internal hierarchies may be shuffled around a bit—perhaps a new seating order at Sunday brunch—but there is widespread assurance that the status quo will remain intact.

TOBG achieves this by making the bad white people so cartoonishly deserving of censure that most white people will have enough plausible deniability that they’re the ones being targeted. There’s the unsubtly named Richard Wagner, the old white patriarch who runs Nella’s publishing house and is involved in all sorts of sinister machinations. There’s Colin Franklin, the egotistical older white male superstar writer who thinks he’s being authentic by having a black mammy-like character named Shartricia in his latest novel. There are the young white co-workers who think Shartricia is pretty neat. The novel is really more about Nella’s insecurities about her own blackness anyway, about how in the black neighborhood she grew up in, “Black kids would see her holding hands with her white boyfriend in the hallway or eating lunch with her white friends in a café and whisper to one another, not very discreetly, there goes the Oreo.” Nella would’ve been a great satirical character of a black woman trying too hard to be a shallow social media-poisoned version of blackness.

Don’t look in your lap, said [Nella’s] inner Angela Davis, and then another Davis spoke up. Viola. You is kind. You is smart. You is important.

- The Other Black Girl

With such cringeworthy self-exploration masquerading as industry satire, why should anyone on the inside feel scared or even offended? In an interview with the Washington Post, Harris even expresses her relief that “having publishing see this book and feel like I got it right and not being offended was really, really great for me.”

As for what Yellowface is really about, instead of a call to overturn everything in publishing, it’s really a broadside in the slow-burning interracial intra-gender war between certain types of white and Asian women. Some may interpret Kuang’s authorial decision to center the story on a white woman as narrative generosity, but it’s an act of pure indirect aggression: to ventriloquist your enemy and make her a witless sadsack who’s terminally jealous of another prettier and more talented woman whose race, educational background, and writing style are curiously near-identical to your own. As Sheluyang Peng wrote in his review for RealClearBooks, “Kuang is a fantasy writer by trade, and this book serves as another fantasy, where Asian women replace white women as the new American ‘it girls.’”

A few years ago, I wrote about a tendency I’d noticed in media created by white women, in which diversity regarding Asians was often portrayed with an Asian male love interest and/or an Asian female rival. The best example was Girls (a show I’ve developed an encyclopedic knowledge about due to my countless rewatches). Of the few Asian characters there are in the show, the two straight Asian guys—Yoshi and Byron—get romantically involved with Shoshanna, while the most prominent straight Asian female character—Soojin—condescends to Marnie from a superior social tier. On a meta level, the real-life person who achieves Hannah’s (Lena Dunham) professional dream—to be a celebrated personal essayist—is Jia Tolentino, an Asian American woman.

Even back in the 1990s, Joan Walsh was trying to diagnose why exactly the white men of San Francisco were pairing up with Asian women. For decades, Asian American women must’ve been grinning and bearing this from their white female peers while seething underneath. Last year, Elaine Hsieh Chou wrote a piece in Vanity Fair attesting to this long-standing resentment among Asian American women: “Our oppression by white men is persistent and obvious; our oppression by white women is just as persistent, only better concealed under the false assumption that because white women also live under the patriarchy, they are incapable of causing harm.”

I’ll never forget an online correspondence I had with an Asian American woman (let’s call her Alicia) years ago, in which she told me the pent-up fury she had over how white girls had treated her, and how oblivious guys, especially Asian guys, were to all this. Her white female so-called friends would first make fun of her for being interested in Asian guys, but then only try to set her up with white guys that they themselves didn’t want. And if she garnered the attention of an actually attractive white guy, they’d chalk it up to his perverted yellow fever. And to top it all off, Alicia’s Asian male friends would think those white girls were so hot and sweet and fun.

It’s a basic social logic that anyone can intuitively grasp: provided we’re straight, when it comes to out-groups, we will be more friendly towards the opposite-gender while perceiving the same-gender as threats. There’s a popular meme I’ve seen around, the one with two crude stick-figure drawings, with one labelled the “‘I hate white people’ gf” and the other “white bf.”

The attitude in the meme may seem hypocritical, but it makes sense once you ignore the social justice obfuscation (e.g. “Death to white men”). To a woman of colour, chances are very high that her most personal encounters with white racism are from white women because we generally socialize in same-gender settings. White patriarchy is an abstract concept, while toxic white femininity will have been a daily personal plague. Therefore, “I hate white people” should be understood more as “I hate white women.” “I hate white men” may also be kind of true, but there’ll always be a significant carve-out there, because unlike white women, a white man can be the ultimate validating romantic partner for a woman of colour, especially one who’s felt tyrannized by white women all her life.

So if June is this twisted white woman, one who’s immoral enough to steal her dead friend’s work not once but twice, and who also believes that this dead friend was emotionally complicit in her “maybe-rape” (by allegedly using its details in a short story), then wouldn’t she have more vicious thoughts about Athena instead of constantly worshipping how beautiful she is? There would’ve been endless fuel for June’s depraved meanness. Asian Americans have gotten a reputation for having hair-trigger sensitivities to cultural appropriation, but the fact is that Asian Americans have thoroughly copied white people, none more so than socially elite Asian American women who’ve successfully mimicked white women’s fashions, hair colours, education levels, cultural mannerisms, and even racial taste in men. There’s plenty for a borderline personality like June to seethe about. But instead, all she’s allowed to do is mope about how much god-like talent Athena has, how beautiful Athena is, how graceful Athena is, and sigh yet again about how pretty Athena is.

There’s an instance where June discovers that Athena received online attacks for having a white boyfriend. One would think that if June was willing to figuratively rob Athena’s grave—and, let’s not forget, June thinks of Athena as a kind of a rape accomplice—she’d give into her dark side and gleefully join the attackers, if only for a moment. But instead, in this instance, June completely sympathizes with Athena, refusing to hit her where it likely most hurts. It’s a predictable narrative choice, one that reflects Asian American writers’ simultaneous obsession with this topic of white man/Asian woman relationships and refusal to write about them at any level deeper than c’est la vie.

A truly nasty and unhinged June could’ve made for a memorable character, even a disturbingly likable anti-heroine. But that would’ve precisely been the problem. The novel’s supposed to be a gauntlet of humiliation for June and what she represents, and vindication for Athena and what (and whom) she represents. Athena’s flaws in the novel aren’t even real ones, with her biggest one being her tendency to supposedly steal stories from the many people whose lives she’s curious about. But that can be characterized as her just being too much of a born storyteller. Even her misuse of June’s “maybe-rape” can be questioned as June perhaps being delusional and narcissistic.

Yet for all of Yellowface’s resentments against white women , it was still deemed harmless enough that Reese Witherspoon, one of the whitest women of all time, picked it for her book club.

As for when perceived legitimate threats show up, the mainstream publishing and literary world bares its fangs quite readily. In the fall of 2022, Alex Perez gave an interview to Hobart Pulp in which he brutally satirized publishing along similar lines as Harris and Kuang supposedly did:

“Uplift minority voices” is woke white people talk. If they really wanted to uplift minority voices, they’d diversify their hiring practices and hire black female editors, Hispanic dudes, old Asian ladies, and other actual “marginalized” people. I’d love to read books selected by an old Asian lady or one of my half-literate Miami Cuban friends, but that would never happen, of course; that 80% of editorships/agent gigs taken up by the woke white ladies would have to shrink, and those careerist gals can’t allow that to happen. They want to wear their little tote bags and hang out in their midtown Manhattan offices with their fellow career gals and go to lunch and brunch. It’s a sweet life, I get it, I wouldn’t give it up either.

- Alex Perez

But there were no glowing NYT pieces on Perez, no self-reflections among those in publishing about whether they needed to do better. Instead, there were mass resignations from Hobart, followed by a day or two of Twitter warring over how toxic Perez and Elizabeth Ellen, his interviewer and editor of Hobart, were. The Computer Room podcast has a good episode about the incident. Though Perez drops terms like “pussy” (which he acknowledges as part of playing a persona), his critiques are substantively the same as those of Harris and Kuang, yet their receptions by the industry could not be more starkly different.

The reason is that Perez is perceived to be a genuine threat. The obvious differentiator between him and Harris/Kuang is gender, but in his essay “Damaged Women,” Perez advocates for female writers like Allie Rowbottom, Stephanie LaCava, and Tess Gunty to be among the the leading voices of fiction. So it’s less of a matter of whether it should be men or women that should be more prominent in literature, but which women. Harris and Kuang are already part of the established club, having been fast-tracked to success. Even other women are looked upon with suspicion if they’re not perceived to be part of the same team enough. And a guy like Perez has no chance in hell.

I don’t want to be pure salt and bitters, though, so I’ll end things by praising a novel explores the darkness of writers, writing, and the envy and prejudices that poison these worlds. Apartment by Teddy Wayne is told from the perspective of an unnamed Narrator who enrolls in Columbia’s MFA fiction program in the mid 1990s. An awkward and unfortunately charmless young man, the Narrator quickly finds himself as the picked-on kid in his class. Luckily, his one ally turns out to be the most gifted student, a working-class Midwestern fish-out-of-water named Billy. The two quickly become friends, bonding over their mutual alienation from the rest of their peers. The Narrator is living in his great aunt’s rent-stabilized apartment in Stuy Town, and he takes on Billy as a rent-free roommate after learning that Billy not only works long hours at a dive bar, but also has to live there as well.

The set-up is somewhat similar to that of Yellowface, with a less-talented protagonist becoming consumed by jealousy over a more gifted and more attractive friend. But the crucial difference is that in Apartment, the author himself clearly identifies more with the pathetic anti-hero. Unlike the Narrator, Wayne is an extremely talented writer. But from his biography, he’s also obviously not Billy, the under-educated wunderkind from the relative boonies who bewitches the effete metropolitans with his throwback rugged masculinity and matinee idol good looks. Wayne is one of the best contemporary writers at expressing the many daily humiliations that fall upon young men who just fall short of something—whether it be talent, sex appeal, charisma, or all of the above—and the depraved thoughts and actions that can flow from one too many of those experiences.

The Narrator constantly has to be confronted with the fact that Billy is a better writer than he is, can get women on any given night unlike him, and makes friends much more easily than he can. The only thing the Narrator can offer him is his middling (if spacious) apartment that he’s staying in illegally, as well as the allowance his father gives him every semester. He’s essentially the money, but not even the glamorous kind; just the forgettably middle-class type.

Here was a real writer, [Billy’s] photos said, not only because of his single-mindedness, but because that focus suggested he was undaunted by the darkest corners of his psyche—that when he wrote, he wrote something true.

- Apartment

There is much to admire in a writer like Wayne’s refusal to engage in the most loathsome type of literature, which is that of self-flattery and humourless score-settling. Apartment is written in a way that does not make the author out to be the sympathetic sufferer of fools like in TOBG, or the impossibly talented and beautiful object of her social rival’s envy like in Yellowface. There’s no pretense of virtue that’s just an attempt to mask vindictive pettiness and insecurity.

The truth is that vindictiveness and insecurity are narrative gold! But it has to be honest and well thought-out. It can’t be laughably shallow like TOBG, replete with horrible pop culture references as attempted shorthand for black identity awareness. Nor can it be two-faced church-lady self-righteousness like in Yellowface, which could’ve been great if it dared to actually gets its hands dirty by featuring either a viciously honest white or Asian female anti-heroine.

Alicia, if you’re reading this, you should write a novel.

Frankly the disparity in the treatment of Yellowface (and TOBG) vs what's-his-face is not super complicated. He is advocating for diversity of thought, they are advocating for diversity of skin color only. Also, he is calling out woke white people, who actually exist in the publishing space, they are calling out racist white people, who don't. Their "parody" is attacking imaginary people who don't exist in order to advocate for more of the same, his is attacking the real people that do exist in order to argue for a fundamental change to the system.

I good way of finding out home many copies a book has sold is to see how many reviews they got on Goodreads. The Other Black Girl did not do well and I don't thing Zakiya Dalila Harris will be getting another book deal. Yellowface is a modest hit, but it is not as popular as Babel and The Poppy War trilogy. R. F. Kuang's flame seems to have brunt too bright and too fast. I listened to some reviews of Yellowface on YouTube and they all came to the same conclusion: R. F. Kuang is extremely intelligent, highly educated and has an astonishing work ethic. She has also been isolated in silos of White dominated privilege her entire life and lacks the experience, insight and maturity to write immersive fiction. She's passionate and didactic, struggles with nuance and humility - all the usual flaws of ambitious and talented youth. She's only 27 and Harris is 31. I hope they both grow as writers and people, and are able to gift the world with good, honest writing in the future.