It’s now almost August, which is already making me reflect on summer (I was never good at living in the moment). In the middle of June, when summer still looked neverending, I went to the Secrets Reading in NYC hosted by

. It was a memorable event full of great readings, where for at least one night, there was a literal church of literature.Taking a look at the crowd that night, my guess was that it was probably 90% full of 20-something women. I couldn’t help but feel a mixture of admiration and envy that such a culture had been established for these writers and audiences. A friend of mine.

, was among the readers, and when she was up there, I had to wonder how elated she must’ve felt, to stand on that pulpit and see such a crowd, hungering for her experiences and ideas.There’s been rising discourse about the dearth of young straight male writers who once dominated literary scenes. The latest mainstream inquiry has come from Esquire,1 where Katie Tobin asks where all the “sad boy literature” is. Just this week, Dazed got in on the action as well.

has written an excellent response2 to the Esquire piece and I plan on writing my own take in the near future, likely in a review of Tony Tulathimutte’s upcoming short story collection, Rejection (pre-order it because it’s great).Yet all this talk about the search for so-called sad boy novels runs the danger of becoming insular. I, and others like me, have a personal interest in this topic because we’re straight, male, and have major writerly ambitions. But ultimately, the world of fiction—especially literary fiction—is a niche one.

So let’s, for a moment, forget about the exclusive world of literary fiction. What about personal essays, especially in the online sphere where there are no gatekeepers and anyone can self-publish whatever they want? Even then, we seem to have similar issues that exist in the literary fiction sphere, as

has noted.3 I’ve been on Substack for a little over a year and though I’ve enjoyed reading about the perspectives of many different types of people, I haven’t come across many from young (20-something) men that openly discusses their personal experiences, with some exceptions.4 Maybe that’s because I’m not a 20-something guy so I’m just unaware of certain circles. But demographic difference hasn’t stopped me from seeing and reading a lot of young female writers, to the point where I feel like I know so much about Brat without having heard a single song from that album.The youngest of the male writers I commonly come across here seem to be in the 30-something crowd, which uncoincidentally is the age group that came of age when the exalted young literary stars were guys like David Foster Wallace, Bret Easton Ellis, and Jonathan Safran Foer. We Millennial guys may be the last bunch that looked up to our contemporary male writers as aspirational.

It’s also not a case of the marketplace of ideas simply crowding out supposedly stale straight white male perspectives in favour of previously ignored voices. Because I don’t see any flourishing of straight men-of-colour perspectives either. Furthermore, such perspectives would likely be classified, or be criticized, as being little different from their white counterparts anyway (for example, The Root infamously asserted that straight black men are the white people of black people5).

Years ago, my friends and I started Plan A Magazine, an Asian American cultural and political online publication. Something I noticed while writing for and editing that magazine was how the vast majority of pitches we received were from women, even though we were mainly known for offering Asian American male perspectives. I was happy that a lot of women wanted to write for us and we published many of them. But I was also perplexed and frustrated at how reticent young Asian American men were being, even with respect to a publication that had repeatedly proven that we would listen to and respect their honest thoughts. I did, however, receive lots of DMs and emails from these shy guys, asking me to write about this or pod about that. It all seemed rather cowardly.

One might argue that the same dynamics that have chilled male perspectives in contemporary fiction have had a downstream effect on personal essays too. But I don’t fully buy it, especially not on a platform like Substack that is home to lots of cultural exiles. And it wasn’t as if decades ago, before the era of cancel culture as we know it, there was some flourishing online culture of young men writing frankly and publicly about their formative experiences. I don’t ever remember an XOJane for dudes, for better or for worse.

But much like how Boryga asked whether we actually want male vulnerability in novels, do we even want male personal essays? The confessional type of personal writing that’s been popular for a while now inherently favors female writers because no matter what people’s political and cultural affiliations are, few genuinely respect whiny and weak men (unless those men can convert those qualities into raucous humour, which is why stand-up comedy has traditionally been so male-dominated). A crying woman is beautiful and vulnerable in a way that can heighten her socially valued femininity. There is no such boost for a man who does the same (and for he who tries to, he eventually gets outed as an opportunist, pervert, or worse).

Many don’t even want confessional essays from women, that the “first person industrial complex” was a mistake of the early digital media era that harmed and exploited its young female writers. But personal essays do not necessarily have to be exploitative. Whether it’s at the Secrets Reading or Confessions at Sovereign House, stories of vulnerability are often within the safe confines of the respective social codes of their environments.6 Still, the personal essay offers so few degrees of removal between author and audience that more so than any other literary format, the author becomes the product. A man, at least a straight man, who reveals too much is perceived as weak. And there is no market for weak men. Guys gloat that posting L’s is strictly a women’s thing. The straight-male confessional essay becomes the equivalent of the straight-male selfie.

But that type of confessional personal essay isn’t the only kind of essay that one can write to express oneself. When men try to write like women, it rings false, and we shouldn’t do it. I remember when #MeToo was on the ascent and some men would pen essays detailing their own victim narratives and there was something off about how these stories were being narrated. It was like listening to a piece of music being played in a key too high or too low. So in terms of personal essays, young men just have to find what genuinely works for them.

In her Esquire piece, Tobin wonders why straight male writers don’t write more about sex and intimacy. But if such writers were to write honestly, how would those writings be received? In a familiar sitcom setup, a woman asks a man what he’s thinking. The joke is that he should never be honest because the truth will upset her immediately or give her ammunition to use against him later.

For all the ideals of social progressivism, some genderized double standards continue to exist, sometimes enforced by progressives themselves. A woman writing frankly about having sex with a man would not be considered the same as a man doing the same about a woman, for understandable reasons. There’s a reason that revenge porn is much more harmful to women than to men. But does that then mean me cannot ever express ourselves honestly about important topics that women like Tobin want to hear from us about? Does this mean women want men to lie to them, but convincingly? Maybe some do, but to think that most do would be severely underestimating women.

The truth is that women and men are never going to see eye-to-eye with one another on everything, especially when it comes to dating and love and sex. Part of the maturity process for men is to be able to accept this without turning into a simp or a psycho. Most young men fall somewhere in the ever-shifting middle, sliding closer to one extreme and then the other from moment to moment. It’s a confusing place to be, which explains why many of the confident young male voices we do tend to hear tend to fall into the simp/psycho dichotomy.

I’m sympathetic to this uncertainty. When I first began writing seriously on the internet, I used a pseudonym (Oxford Kondo) because of the freedom it gave me. I was planning to write mostly about Asian American issues and given that (1) it was the mid/late 2010s when 2nd-generation Asian American Millennials were getting all our pent-up emotionally stunted identitarian drama, and (2) I’d be writing from a straight Asian male perspective, I knew there’d be tons of criticism thrown my way. At one point, Celeste “DAWN CAN GO FUCK HER ONE KIDNEY” Ng7 got involved.

I eventually shed the pseudonym around 2019 because I no longer liked feeling that I had anything to hide behind. In 2022, an essay of mine8 was published in Current Affairs, a piece that was much more pointed than anything I’d written before that had gotten me into trouble. Still to this day (including today), I meet people who tell me how much they love that essay.

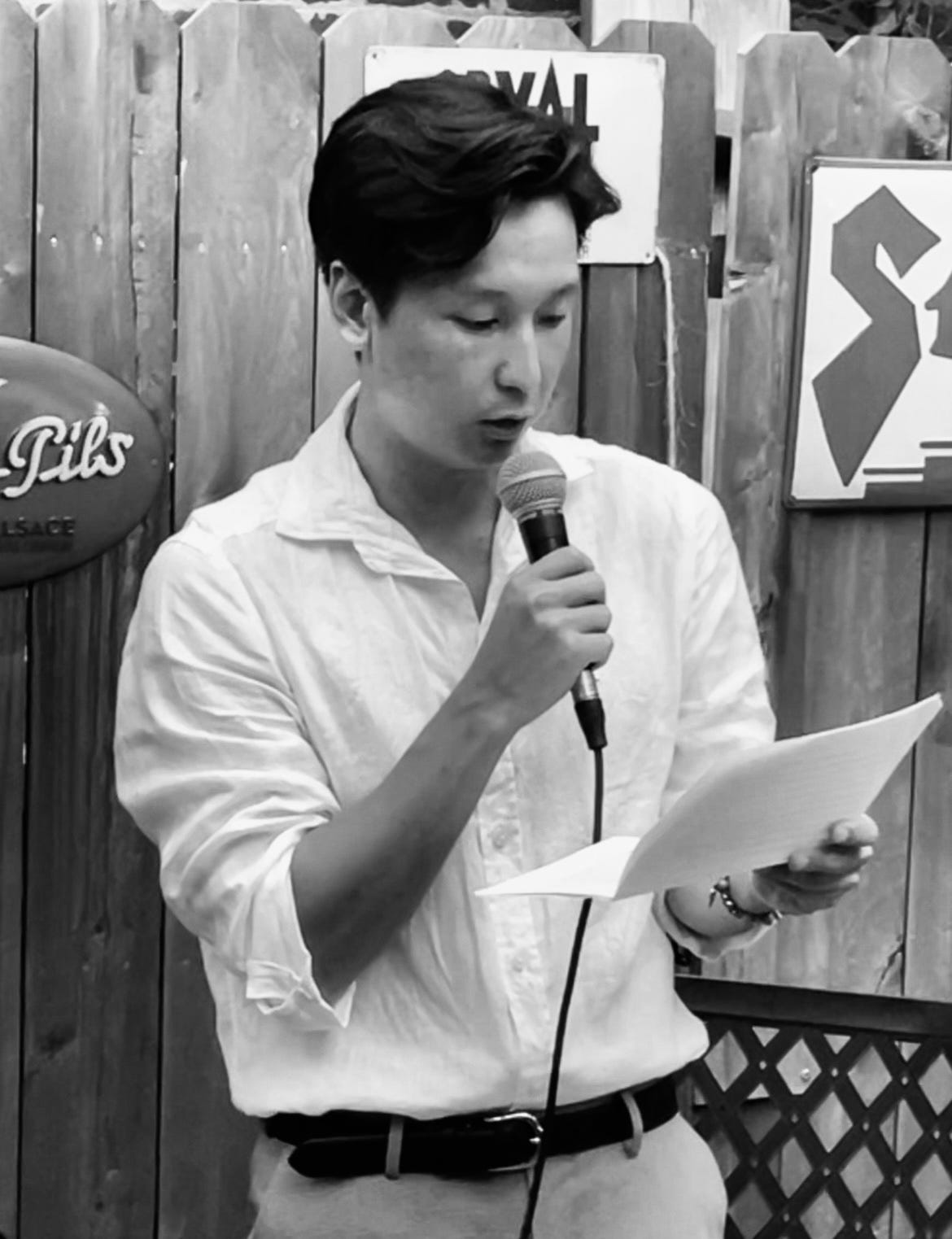

And just recently, The Cleveland Review of Books hosted an issue launch party and they were gracious enough to allow me to give my first literary reading. The night meant a lot to me because back in 2018, Electric Literature essentially pulled a piece of mine they’d just published the same day because they found out I was Oxford Kondo. They called me a racist and a misogynist. Yet six years later, I was still at it, still writing about similar things, but in a newer and better environment. Nobody misses 2018 culture.

All this is to say that I understand why some young guys stick to anonymous places like Reddit, 4chan, etc. It’s their safe spaces. Now I can look back at those aforementioned fraught times with fondness, even wondering what all those people I had online fights with are doing now and wishing them well. But when I was living through those days, they were unsettling times.

Now that I’m older and more experienced, it’s tempting to act as if I’m above the fray, to fully indulge in being disdainful of sadsack guys that seem to enjoy wallowing in their self-pity and laziness (except when falling for get-rich-quick schemes). But there’d be a performative element to that, to pretend that I don’t completely get where they’re coming from lest I be tainted too. So that I can be the only boy in the world.

One might say, who cares about writing? I’m aware that there are other media forms out there like short/long-form video and lots of young guys are sharing their experiences there. But writing is one of the most basic and also lasting ways to express yourself. It’s one of the most intellectual skills that you’re taught and there’d be something greatly amiss if one gender self-exiled itself from this endeavor. And if you don’t write about yourself, you don’t really respect yourself.

They say how hard it is to make friends these days, especially as you get older. But I’ve never found this to be that true and it’s because I’ve met so many people, including some of my closest friends today, through my writing. I never would’ve met them otherwise. I don’t want anyone to miss out on that. This aspect of writing and reading is far more important than who’s getting six-figure publishing deals and which literary style is in vogue.

Because what else is there with writing? Money? Hardly ever was and even less so now. Fame? Ms. Hawk Tuah became more famous in 10 seconds than 99% of published writers.

And yes, there’ll be clashes and judgments cast. So be it. I’ve lived through them. I’ve upset people with my writings and I revel in that. At other times, I’m regretful. It’s not the end of the world. I’ve always liked

’s definition of masculine writing as something that does not have to be hateful of women, but instead, just has to be indifferent to women’s judgment.9 And the same goes for feminine writing with respect to any male feedback. Otherwise, we end up with dishonest and pandering writers. Absolutely abhorrent. I’d rather we all be respectfully honest with each other, as opposed to being cloying and fake, or self-segregating into genderized ghettos where our minds and fortitudes rot.It's not like I’ve figured everything out either. Most of my Substack pieces are not about my personal experiences, or at least are not primarily about them. I’m a pretty private person and when I look back at my more identity-based writings from years ago, though I’m proud of them, I’m also filled with a reluctance to return to a way of writing that seems too needy for others’ understanding.

But as a writer, especially a male writer, do I have an obligation to break out of my comfort zone? It’s a question I think about a lot. More so than in previous pieces, I’ve been “vulnerable” (god I hate that word) in this one, talking about the closest I’ve come to public censure. Maybe it’s baby steps and one day, I’ll write more in detail about that time (it involves molly and a CHVRCHES concert in Philly).

Where is All the Sad Boy Literature? | Esquire

Do we really want more male vulnerability in fiction? by Andrew Boryga

Talk to me, man by Amar Patel

Who is the Bad Art Friend? | The New York Times

Asian American Psycho by me

Alex Perez on the Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop… | Hobart Pulp

Chris, between you, Andrew Boryga, and Alex Perez, my list of reasons to put off writing that masculinity piece is getting shorter and shorter.

“Now that I’m older and more experienced, it’s tempting to act as if I’m above the fray, to fully indulge in being disdainful of sadsack guys that seem to enjoy wallowing in their self-pity and laziness (except when falling for get-rich-quick schemes). But there’d be a performative element to that, to pretend that I don’t completely get where they’re coming from lest I be tainted too. So that I can be the only boy in the world.”

You’re a good person for fighting this impulse. That impulse from other men is exactly why I’ve always avoided public vulnerability without anonymity. What I’m scared of isn’t the judgement of non-men, it’s other men using my vulnerability to aggrandize themselves. This is something I’ve seen my whole life in every male space from lunch tables, to varsity sports teams, to a fraternity, to social media. If you ever appear weak, others will loudly exclaim how they can’t relate and don’t understand to perform strength. What’s so annoying about it is just what you said: all these men obviously relate and know what you mean. It’s a stupid performance we’re forced to pretend we don’t do.