"I'm Not An Activist": Reflections on a Milestone Night

A recap of the NYC premiere of "I'm Not An Activist," the new short documentary where Asian Americans fight back

On the wretchedly hot night of Thursday, July 27, 2023, there was the very non-wretched premiere of the short documentary I’m Not An Activist. Directed by (the now Emmy-nominated) Dan Chen, produced by Millicent Cho, edited by Ien Chi, shot by Philips Shum, and funded by Plan A Magazine, the film follows Dragon Combat Club, which describes itself as a “volunteer self-defense initiative preparing people against pandemic era violence.” DCC was formed in early 2020 by Dr. Z as a response to inaction and empty words that were offered as so-called solutions to the escalating street-level attacks on Asian Americans, especially against the elderly and women.

The film is punchy, yet also languid (especially with Ciel’s excellent soundtrack) as it follows various members of DCC like Dr. Z, Jon, Chong, Milly, Fulton, and Nina as they attend nighttime DCC classes under the highways, offer assistance to the elderly in busy subway stations, and everything in between. Later in the panel, Dan would speak about how as an outsider (he is an Angeleno), he wanted to capture a day-in-the-life feel. Though the root subject matter is unpleasant and frightening, the film refuses to wallow in helpless sadness, a learned default Asian American cultural tendency that repulses all those involved in this film. Instead, I’m Not An Activist is less about fear and more about communal bonds, and how people can enjoy life while being brought together by danger. Appropriately, turnout at the premiere was very impressive, causing the top-floor screening room of DCTV at 87 Lafayette in Chinatown to get packed.

Those street-level attacks on Asian Americans don’t make the news much anymore. I’m not sure whether that’s because the attacks have actually decreased or the public has simply lost interest. Regardless, many of us won’t forget how people, particularly some of our supposed community leaders, reacted when these attacks were a pressing issue.

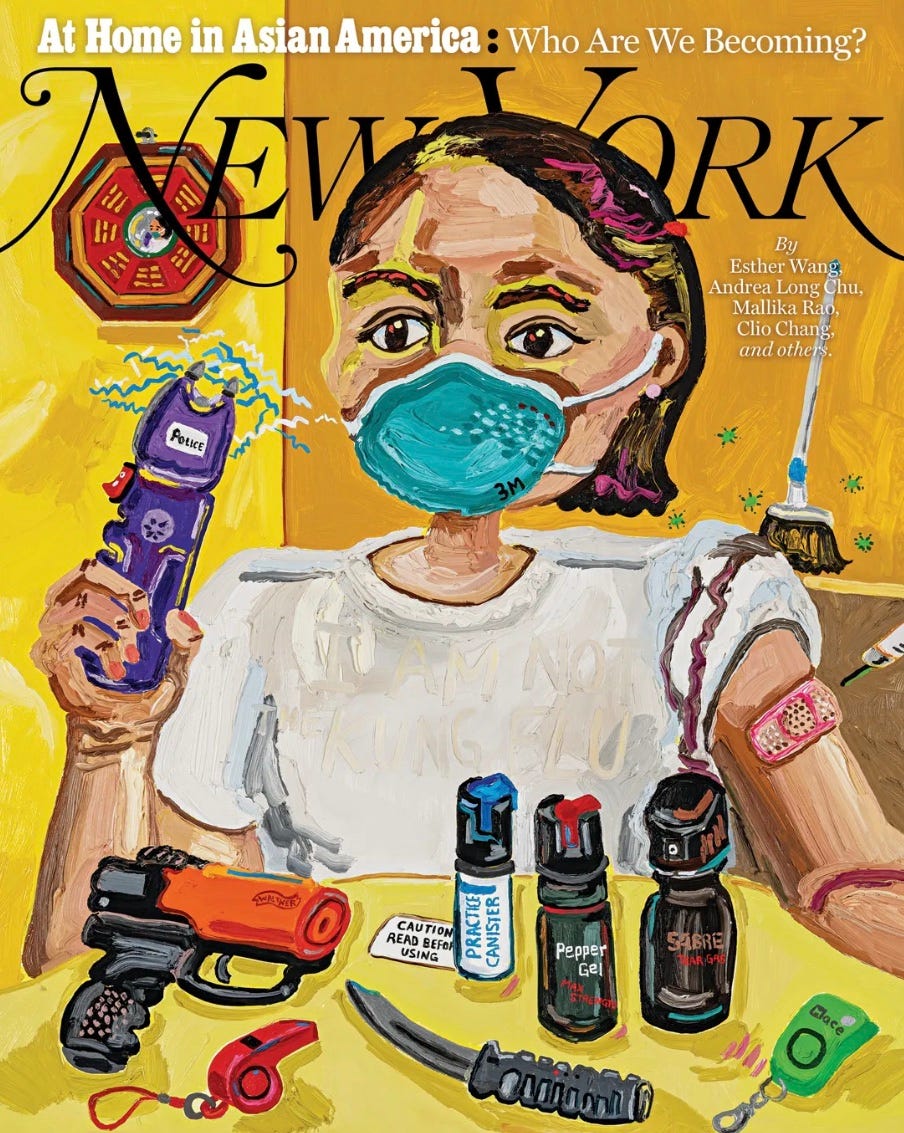

On September 26, 2022, New York Magazine published a piece about these attacks, in which the title described organizations like DCC as “desperate, confused, and righteous.” Many people I knew intensely disliked the cover, which was a telling indicator of the substance and tone of the pieces in the issue. The cover portrayed a COVID-masked Asian woman with an arsenal of self-defense weapons and items: a taser, pepper spray, knife, whistle, what looks to be some kind of flare gun. The image evoked a fobby type of Asian American woman, probably living somewhere in deep Queens in a home with a stainless steel fence. Quite unlike the Asian Americans that write for publications like NY Mag, who likely live in literary Brooklyn. Above her head was the seemingly self-examining question, “Who are we becoming?”

But who exactly was the “we” here? Did these writers truly identify with Asian Americans like the caricaturized woman on the cover? As with so many controversial Asian American issues, the condescension of the Asian American culture class towards the rest of its community was palpable. In the documentary, there is a living-room discussion of why attempts to address pressing and difficult societal problems constantly get shot down by so many. It’s because these types, despite meaning well, ultimately prioritize their own moral comfort above all else, because they have the luxury of doing so. And in difficult situations, doing nothing is the most scenic route in the forking road.

The podcast we did in response to that piece (as well as one in The Nation), “NY Gag,” is actually now our most-listened-to episode of all time. I don’t think that’s because the average Asian American’s most pressing concern is physical safety, though during the worst of those attacks, certain demographics of Asian Americans certainly were justified in feeling afraid. Rather, it was because the muted or even angry denialist response by so-called Asian American spokespeople in response to these attacks exposed, more clearly than ever, where their priorities were. Even when the victims were more or less as “perfect” as they could get in the identity politics power rankings, Asian Americans were made to made to feel as if they were delusional, stupid, or racist for expressing any concern.

The only time Asian Americans were allowed to express any anger was when the Atlanta spa murders happened, and that was only because not only were the victims perfect, but also the killer: a sexually depraved, scraggly bearded young white man who looked like an AI-generated image of an OnlyFans addict. Suddenly, the emotional floodgates opened, if only for a brief moment. Predictably, the conversation was dominated by Asian Americans with the most cultural power, and the introduction of a white perpetrator enabled these types to vent about their pet racial peeves regarding white people, like being made fun of for Asian names and dating woes. There was also fretting over whether #AsianLivesMatter was too much of a faux pas.

By now, it’s no longer controversial to say that Black Lives Matter (the corporation, not the popular movement) has mostly been a grift. But for a couple of years, it had many true believers. I’m not sure if #StopAsianHate ever even had much of a stretch of genuine credibility. Even its name had to be debated, whether “Asian” was inclusive enough or whether it should be #StopAAPIHate. Also, were South Asians part of this? But brown Asian Americans weren’t being attacked as spreaders of COVID or for supposedly being from the land of America’s greatest geopolitical rival, the same way yellow Asian Americans weren’t attacked in years past for being “Muslim.” But South Asians are “Asian” too, or else you’re being an East Asian elitist (says the Ivy-educated East Asian who hangs out in elite media circles). And now, we’ve descended into the usual inanities of typical Asian American activist debates.

Meanwhile, the actual victim demographic of these attacks—often elderly, often female, often working-class—are completely ignored. One of the interviewees of the documentary, Chong—an academic and member of DCC—gave an impassioned speech on the live panel after the premiere, about how some of her Asian American academic peers were so petrified of getting their “hands dirty,” in the sense that while it’s easy to espouse pithy tenets and slogans in their world, reality often comes down to making difficult decisions. She described it as a “[f]orm of narcissism” and “self-aggrandizement,” where “it’s almost enrichment for them to talk about all the problems in the unwashed, unassimilated masses of chinks, which is what they think of us.” She scoffed at the usual platitudes about “investing in communities” and “mental health services,” because “[I]t’s not going to be a healing circle for someone who has been in and out of institutions and prison systems for the last 20 years.” She was particularly scornful about how Asian Americans would get lectured, even blamed, for these attacks because if only we’d just be less racist, less anti-black, less pro-police, and/or less carceral.

What does one do when he or she sincerely believes that America is too eager to imprison people, especially black people, yet Asian Americans, especially the elderly and women, are physically assaulted, often by black men? Is it because it is wrong to criticize some black men, even ones with severe mental health issues and/or long-standing criminal records? Clearly not, since within the BLM movement, there was criticism of black men, like about how black men received too much attention in the movement (even though BLM was founded upon the murders of almost exclusively black men and black men make up almost the entirety of black victims of police killings).

So is that what this version of social justice comes down to? A maddeningly complex, and often hypocritical, code of manners that dictates who can say what at which given time, mostly to air personal grievances instead of solving societal problems?

That’s what the title I’m Not An Activist gets at. The film is for those that no longer care what the Asian American activist or culture class have to say. At this point, it’s not even about being angry at those types. In the panel, Dr, Z rejected the idea that believing such people didn’t care about people like him was a bleak idea. Instead, he saw it as freeing and even hopeful, because it allowed him to do things like DCC, which connected him with all sorts of different people. Staying true to his word, when I asked him for any belated rebuttals to the NY Mag article, Dr. Z said that overly fixating on an old piece would be antithetical to what he and DCC were trying to do, which was to block out the noise and move on ahead, helping out those who need it.

Such an attitude is an invigorating one, and it was evident in the high and lively turnout that night. The evening was emceed by Teen Sheng, who was the driving force in Plan A to get this film made. A resident of Elmhurst, he saw up close the chaos and tragedy of COVID when it first hit New York City, and the resulting fear and violence.

After the screening, Teen led a couple of panels, the first consisting of Dan, Ien and Millie. Dan told the story of how he had first texted me about the possibility of combining efforts to make this film. Unbeknownst to him, we at Plan A had been discussing such a possibility amongst ourselves. Dan’s vision was to create something with “honest, blunt energy,” something that instead of begging for others to help us, plainly exuded “Fuck you, we’re doing things” mindset. He remarked that we rarely ever see Asian American anger because such an emotion is never rewarded, even though anger can also lead to love and connections.

Ien also stressed the importance of making connections, not just in the context of ensuring personal safety, but also in the company that was there tonight, which consisted of Asian and non-Asian, women and men, old and young, visitor and New Yorker. He noted how so many videos that were made in the whole #StopAsianHate movement had a kumbaya and/or melancholic feel, which had their time and place, but also sometimes needed to make way for something more forceful and empowering.

In response to Teen’s observation that the film had a very NYC Asian American identity, Millie noted how as a native New Yorker, she had seen the gradually increasing Asian influence of certain NYC neighborhoods, especially in her home borough of Queens. She noted how in making a documentary, the story is usually found in the editing process, and the spirit of DCC helped instill a “I don’t give a fuck” energy that didn’t care what the mainstream thought.

I first met Teen in the spring of 2017, not that long after I moved to NYC in the fall of 2016. I didn’t know a lot of people in the city at the time, except for a few college friends. With him and several others, we began to talk about something that would eventually become Plan A, and I’ve met many of my closest friends through that endeavour. Friends like Millie and Dan, who are Asian American artists with gorgeous and bold things to say, and who also get what I’m trying to do with my writing. I just met Ien very recently but I’m sure it’ll be the start of a beautiful friendship as well. Every now and then, when I find myself wondering if I could’ve done more in the past X years, I think of that first solitary Christmas I spent in NYC, rooming as a third wheel to a couple in the East Village, with my own Christmas breakfast/lunch/dinner of a large cheese pizza and a four-pack of Narragansett tallboys, and I feel lucky and grateful.

The night before the premiere, a whole bunch of us were at Millie’s apartment, where Dan and Ien were staying during their time NYC. After a dinner at Millie’s (delicious as always), we recorded a podcast. In it, I couldn’t help but reminisce about how in early 2020, we (Plan A) were somewhat seriously considering hosting our first live event. Maybe a live podcast recording. Maybe a social mixer. We all know how the 2020 plotline went and why that prospective live event never happened. Over three years later, it finally did happen, and I have to say, a lot has changed during those years.

The main thing is how there is no more reticence in saying what we say. Asian Americans are given very narrow leeway in what we’re allowed to express, and when Plan A was at our productive peak at around 2018-2019, we got called all sorts of names, mainly by other Asian Americans. An Asian American academic journal at Johns Hopkins even seemed to derogatorily associate me with Frank Chin, which is one of the best compliments as a writer I’ve ever gotten. I stand by everything I’ve ever said or written as part of Plan A, but there’s a reason that at the beginning, I used a pseudonym (Oxford Kondo).

There’s a great scene in the film Snowpiercer, where the protagonist rushes the guards, daring them to shoot him. He puts his forehead right up against their barrel and pulls the trigger himself. The rifle clicks, and the sound of the empty chamber rings out like church bells. “They’ve got no bullets!” the crowd screams, and a melee ensues.

I don’t want to instigate needless fights, though. That night of July 27, people didn’t come to jeer at or gossip about enemies, whether real or imagined. Nobody shuffled in apprehensively, wondering if being at this event would get them labelled this or that. They were to celebrate the work of artists like Dan and Millie and Ien. They were there to cheer on DCC. They wanted to hear from stand-up politicians like Assemblyman Ron Kim, who spoke passionately about how he used the national attention he gained from essentially causing Andrew Cuomo’s downfall to shed light on the stolen wages of Asian American homecare workers (which totally around $150 million). And of course, they were also there to see us Plan A members in person, to verify that we are as hot as in person as we are in our Twitter profile pictures.

I wished the other Plan A founders—Jess Rhee, Filip Guo, Eliza Romero—who don’t live in NYC, could’ve also been in attendance.

At Christmas last year, a bunch of us were at Millie’s. Teen said something about this documentary being a kind of capstone project for Plan A. The statement didn’t make me sad, because for a while now, we’d all known that the energy and ethos that sparked Plan A had changed greatly. It wasn’t 2018 anymore. But it did make me reflective, about what was next. If this documentary was a capstone project, then the premiere was a capstone event, a breaking out of a shell for not just us involved with the film, but also for all Asian Americans that want to think beyond the same old well-worn-out channels of endless squabbling. There’s simply no point in trying to win over people who have a deeply vested interest in not understanding you. Just move past them. There are whole other worlds out there.

PS Congrats to Dan who, on the day of the premiere, learned that his feature-length documentary, Accepted, earned an Emmy nomination. Much deserved!

PPS Listen to the recent Escape From Plan A podcast episode featuring Dan and Ien!

Some more pictures I took at the event (taken on Nikon F3):

Great piece. Glad that you mentioned the Atlanta spa shootings, which gets repeatedly mentioned as THE example of horrific anti-Asian hate, and maybe that’s fair. What I very rarely see mentioned was the official law enforcement response to it. I was living in Atlanta at the time of the shootings, and it was a HUGE deal- TV and radio broke into their programming to report on it and a massive manhunt was launched almost immediately. The perpetrator was, in fact, caught the very same day, and the district attorney immediately held a press conference to announce her intention to seek the death penalty for him. Pretty different from San Francisco DA Chesa Boudin making excuses for a perp caught on tape murdering an elderly Asian man: https://www.nbcbayarea.com/news/local/family-of-84-year-old-man-killed-in-san-francisco-upset-with-district-attorney/2484573/

Asians are victims when it comes time to organize Asian voters and donors for Team D.

Asians are "white-adjacent" when it becomes necessary to organize and focus other groups' outrage.