Rejects R Us

Tony Tulathimutte's 'Rejection' and our modern world of romantic and social precarity

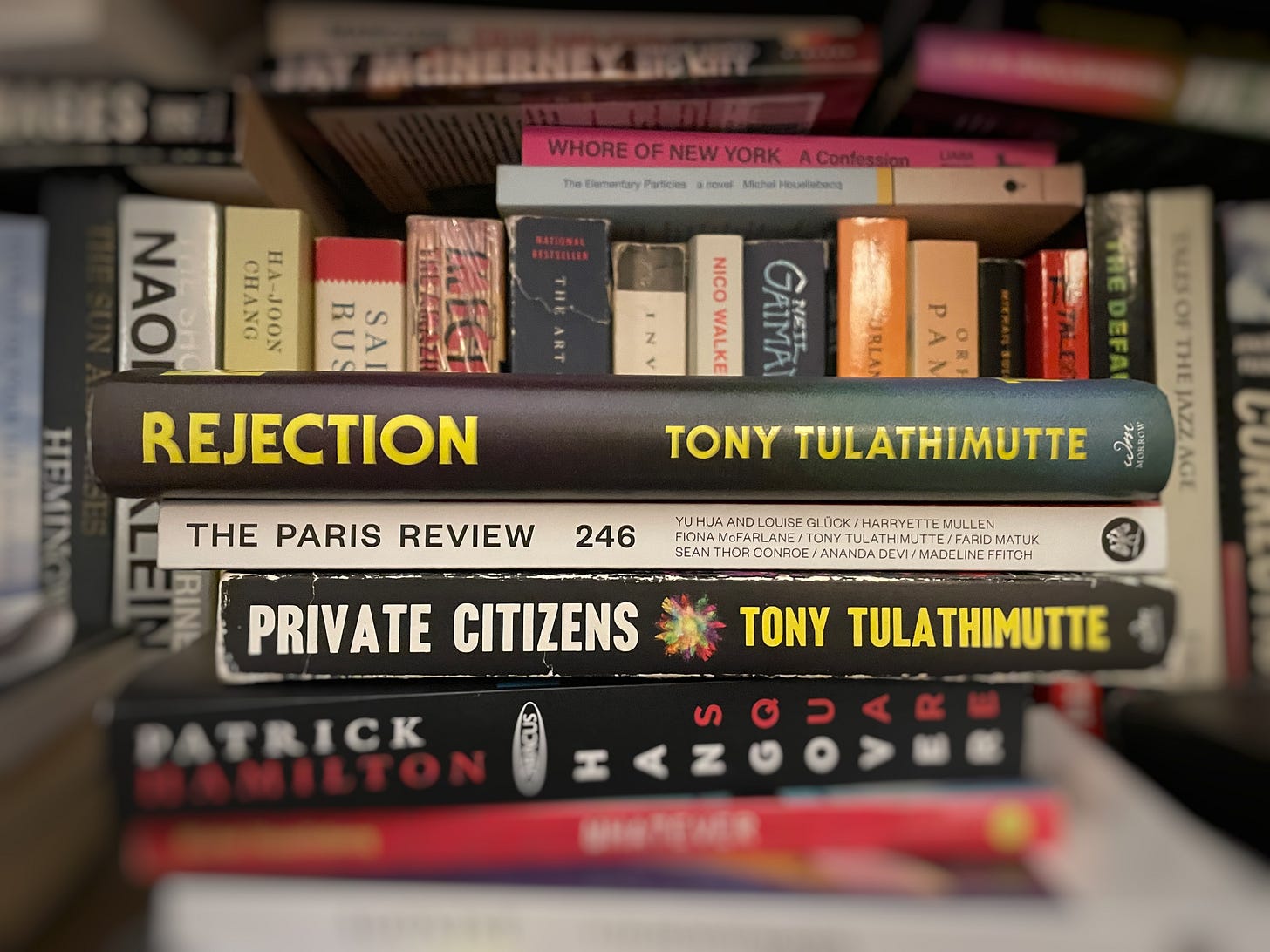

I’ve waited a long time for Tony Tulathimutte’s follow-up to his novel, Private Citizens, which I’ve already written about glowingly before.1 As with Private Citizens, Rejection is a deeply uncomfortable multi-perspective exploration into sexual and social unhappiness in our contemporary times.

I often find myself astounded, and thankful, that a writer like Tulathimutte exists: a relatively young mainstream male writer who writes about these sordid topics, as opposed to an older one who can be safely grandfathered in. When even things like childless cat ladies and couchfucking are elevated to the highest level of our political discourse, it’s nice to know there are good writers who can honestly reflect our sexual and romantic insecurities.

The first three stories (there are five in total, with a couple of odd little add-ons in the end)—The Feminist, Pics, and Ahegao—are the strongest. To oversimplify them, each of the three focus on the romantic frustrations of three distinct types of people. Craig, who is not named in the story but is later identified in another short story, in The Feminist is a straight “narrow-shouldered” white guy who grows increasingly blackpilled over the fact that his pious devotion to male feminism has no effect on his desirability to women. Alison in Pics is a straight lovesick white woman who has sex with a close male friend of hers and begins a downward mental descent when he regards it as a one-time thing and, even worse, soon finds a girlfriend. Kant in Ahegao is a gay Asian American man whose sexual insecurities have warped his desires into outlandish fetishes.

Of the three, I enjoyed Pics the most. Part of that was because I’d already read The Feminist back in 2019 when it was published in n+1. It caused quite a firestorm, and in anticipation, Tulathimutte made sure to tweet that “to be clear in advance, feminism is good, this character is not good.” Carmen Maria Machado also reassured Twitterworld that the story wasn’t dangerous or anything (for context, this was around the time when Joker came out, which was supposed to incite incel rebellions all around America). I actually wasn’t the biggest fan of The Feminist when I first read it because it came off as more like an essay than a lived-in fictional narrative. Instead of focusing on specifics, it felt as though the story had the unnamed protagonist live through a highlight reel of a sexually accursed life, full of cursory details that sometimes read like a trollish r/theredpill post. For instance, Craig’s affliction as a white “narrow-shouldered” man also came off like a cutesy way to avoid entanglement with actual real-life male sexual penalties based on height, race, baldness, etc.

But back to Pics. It’s often thrilling when talented writers tell a story from the perspective of the opposite gender. Alison, who’s in her late 20s, suffers the straight female version of the more commonly discussed straight male inceldom problem, where her issue isn’t attracting men or having sex, but getting a committed relationship. She feels that “[l]ove is not an accomplishment, yet to lack it still somehow feels like failure.” What she wants is “credible vouchsafing of love and admiration from one non-horrible man who finds her interesting and attractive and good,” recalling Hannah’s doorway plea to Adam in Girls (“I just want someone who wants to hang out all the time, and thinks I'm the best person in the world, and wants to have sex with only me”).

One night, Alison’s college friend Neil is over in friendly fashion as usual. She never even found him attractive. But they fuck and it’s amazing. He even asks to take a photo of her holding his dick, to which she says yes. Then the friendship turns weird, they never sleep together again, Alison becomes obsessed with Neil, Neil gets a girlfriend…

Unlike with the other characters of Rejection, it’s not as obvious what marks Alison’s citizenship among this book’s population of perverts, deviants, and psychos. She’s severely caught feelings for a guy, but does that make her all that different from a standard rom-com heroine? Alison does have a fundamentally transactional view of sex and relationships, where she seethes that Neil “got everything he wanted, and she got nothing” because he “had his little ego boost, his little pump-and-dump with a keepsake pic to beat off to for the rest of his life.” Despite her brain telling her that there’s nothing inherently wrong with casual sex, she places little worth on the admittedly orgasmic sex she and Neil had (“[s]he cums so hard it makes her sit up”) and she can only dwell on what she feels ought to have happened after. She complains in her chatgroup that Neil sucks because “he gets to feed his ego effortlessly without any of the hard work of relationship maintenance.”

But if she’s already characterizing relationships as something she desperately craves but for Neil, and perhaps for most guys, is joyless drudgery, then why would guys be eager to jump into such unions with her? Because they owe her because she gave them sex? Isn’t that the mere reverse of the entitled incel mindset that is repeatedly condemned as toxic?

Does Alison even actually love Neil? Until the night they sleep together, “she’s never thought he was hot, until now, the moment she realizes he thinks she’s hot.” Is he just a vessel for her ego?

Still, I felt for Alison. There is something very calibrated about Neil, as if he has those special goggles that can see laser tripwires, enabling him to carefully conform his actions to not set off any alarms. This is most apparent when he sends a scolding email to Alison after she acts jealously and rudely at dinner with Neil and his friend (and future wife), Cece. Alison, against her better judgment, sends a simperingly apologetic email, to which his curt and smug reply doesn’t offer even a conciliatory “I’m sorry too.” Then again, the whole story is told mainly from Alison’s perspective so maybe he’s justified in being fed up with her near-decade’s worth of sadsackness, kind of like how Craig’s queer female friends eventually get tired of his incessant self-pitying.

Tulathimutte’s gift is his ability to highlight the hypocrisies of the social winners that surround his flawed protagonists while also allowing those protagonists to stew in their own grotesqueness. It’s what made me appreciate the intricate construction of The Feminist more upon my re-reads. For instance, when Craig is chewed out at a picnic by his group of progressive friends for voicing his romantic woes one too many times, he is told by his supposed close friend (Bee from Main Character, as it turns out) to “Suck it up, you bitter little boy, and move on.” He counters by saying that he listens to their dating complaints all the time (mostly about their “stupid anxieties about dating bi women”), to which he is met with a “Wooooow-ow-ow” and a “You really don’t want to press this.” Afterwards, Craig’s friend and he both engage in passive-aggressive sub-tweeting, with the winner determined by how many strangers like their posts.

So it’s not that fuckability politics is nonsense; it’s that only some people’s fuckability politics are elevated to the heights of great societal concern and others’ are relegated to the get-over-it-lol tier. Masquerading as a humanitarian framework, it’s actually a cold and calculating one that places highest veneration to fashionable online social mores instead of actual personal relationships.

Alison gets a taste of this as well. Neil’s girlfriend, Cece, is Korean American, which makes Alison similar to Cory in Private Citizens (who makes a cameo in a later story, Main Character) in that they’re both lovelorn white women with major body image issues who lose their dream (white) men to more attractive and cooler women of colour (Henrik, the object of Cory’s affection, falls for Roopa, a gorgeous Indian American neo-hippie). One of the more pointed suggestions of Alison’s villainy is when in her groupchat, she accuses Neil of having an Asian fetish, which raises some eyebrows there. But enough white men openly admit to such a fetish, and enough Asian women report experiencing it, that if it was meant to condemn Alison as some unsympathetic bigot, it doesn’t quite land.

Despite the groupchat’s apparent intimacy (evident in the sexual jokes and stories, which are admittedly very funny, that are shared with carefree abandon amongst them), Alison is quickly discarded after she hosts an ill-advised dinner party, from which an argument involving a raven, a young child, and primrose vagina oil (I won’t say more). For all their feminist girls’-girl righteousness, the groupchat instantly resorts to attacking Alison on her looks and age when they fight. Long-standing resentments—the younger and hotter women who’ve moved up more in the media world than Alison think she’s a drag and she’s sensed it for a while—collide like the SS Mont-Blanc and SS Imo, leaving Alison alone amidst the rubble of her own Halifax.

I first read Ahegao in winter 2023 issue of The Paris Review. It’s a fine story with the most memorably bombastic writing in the whole book, with a climactic orgy of a literary sequence that makes Mooj’s degenerate monologue in The 40 Year Old Virgin seem like a Mother Goose nursery rhyme. But having read Private Citizens, Kant comes off a bit too much like a gay-swapped version of Will from Private Citizens. They share many similarities: short Thai-American men who get bullied a lot as kids and who become techno-perverts of the craziest order.

Our Dope Future and Main Character round out the rest of the stories and they’re not as memorable as the first three. Our Dope Future is written as an extremely long Reddit-style “Am I The Asshole?” post from the perspective of a painfully deluded, possibly autistic, white tech bro named Max (who becomes obsessed with turning Alison into the Eve to his Adam). While the story does showcase Tulathimutte’s deft ability to intentionally jampack as much cringeworthy slang in a narrative as grammatically possible, making fun of tech bros in 2024 comes off as interesting as making fun of hipsters in 2014.

Main Character has a mind-boggling premise of a young tech mastermind, Bee (Kant’s younger sister), who perpetrates a massive online troll hoax that suggests that every Twitter villain you’ve ever seen (except Donald Trump) was actually a bot created by her. If the world ends in nuclear war due to social media culture wars, it was all Bee’s prank kekeke. Since Bee shares a lot of biographical facts with Tulathimutte and goes on long rants about her gripes about what it means to be Asian American, Main Character felt like Tulathimutte’s venting about race. Bee’s observations aren’t wrong (like how there are mainly 3 ways for Asian American kids to deal with race: assimilate into whiteness, appropriate blackness, or cosplay Asianness). They are also reminiscent of Will’s internal invectives about Asianness in Private Citizens, which I found intriguing. But Will was speaking from an angry straight Asian American male perspective, one that we don’t often see voiced in polite society, and it was back in 2015, when it was still somewhat novel to trashtalk white liberals, boba liberals, and their ilk. Bee’s thoughts are not wrong; they’re just blah.

I do appreciate that Tulathimutte has to walk a very fine line as one of the very few young-ish straight male writers that are considered eligible for things like the National Book Award. In the final part of Rejection, Tulathimutte “leaks” (what I presume is) a fake literary rejection that calls him out for trying to have it both ways by (1) writing with brutal honesty about taboo subject matter about dating, sex, and love, but (2) conveniently leaving himself, or his own identity, out of it. If you’ve read Private Citizens, you’d know that he has no qualms about opening himself up to scrutiny since the sexually twisted character of Will is a short Thai-American older Millennial straight tech-savvy male who graduated from Stanford in the 2000s. Tulathimutte has even said Will is some version of himself.2

But of course, many readers of Rejection may not have read Private Citizens. Even so, that such a meta epilogue is seemingly necessary for this book just speaks to how uncomfortable, yet obsessed, with its topics we all are: we don’t want to be tainted by these issues’ wretchedness, but we’re all dying to find a way to somehow discuss and debate them. So any writers that are willing to put their name, face, and credibility on the line to do so gets a ton of respect from me.

A complaint I do have about Tulathimutte is his tendency to end his uneasy stories with such downer codas that they come off as moralistic. Reading about how Craig, Alison, Max, and Bee end up can feel like reading one of those Give Yourself Goosebumps books where every ending has you being eaten by some monster. A truly grim ending would have one of these types win at the end. But are we ready for that?

One idea I had for this review was to pair each story with one of my own rejection tales. As fun as that would’ve been, it also would’ve bloated this review (it’s long enough already as it is) and steered it toward being something else, and I wanted to maintain focus on the book itself. That being said, I do want to end this piece more personally about rejection because I do think we live in socially and romantically precarious times. If previous eras were defined by stultifying social claustrophobia where you were weighed down by all sorts of existing bonds and obligations, the modern world is more defined by brittle and fickle connections.

Are we subject to rejections now more than ever? It’s something that’s probably difficult, maybe impossible, to quantify. And it’s not as if people didn’t suffer catastrophic rejections, like excommunications, in the past. About a month ago, The New Yorker published a piece, “Why So Many People Are Going ‘No Contact’ With Their Parents,”3 which reflects the growing idealization of found families where political views and cultural tastes can all be aligned. The day may come where it will be not that big deal to effectively divorce your family. But if we can no longer rely on our families to be our physical and emotional Alamos, then whom can we rely on? Our friends? Like those in Rejection?

Fewer of us stay in our hometowns, working at just one (or two) jobs our whole lives, which means we have to often (try to) make new friends. Dating apps paradoxically dull the sting of rejection by making it just background noise in your everyday existence, where every time you don’t get a notification, you can safely assume somebody has passed on you. Colleges purposefully entice more applicants just to turn them down to lower their acceptance rates.

Jose Mourinho once famously derided Arsene Wenger as a “specialist in failure.” I don’t think I’m a specialist in rejection, but I’ve certainly become a veteran of it. I think it was my the first summer back from college, which would be my last few months before both my family and I would leave Vancouver forever. I told my best friend from high school that I wanted to get rejected enough times that I would simply become immune to it.

My first clear-cut rejection would come soon enough, in first semester of sophomore year. I was working at a school-run pizzeria and had become smitten with a co-worker. She was a senior and looked like what I imagine Amal Clooney looked like at 22. So I had zero chance. Still, I knew she was single (it must’ve been through Facebook, when people still advertised their relationship statuses, or lack thereof) and that I wouldn’t be able to live with myself if I didn’t try. So I signed up for the same shift as her, hoping to catch her alone when we clocked out. Hopefully, nobody would be around to witness my likely humiliation. But whatever. Anything was better than being a coward. During the last 30 minutes of our shift, I remember nervously watching the clock, not saying a thing. I was probably rolling out pizza dough in a catatonic manner.

Luckily, I did manage to get her alone. I said something about wanting to take her out to dinner sometime. She said I was very sweet and brave for asking and that she’d think about it. To me, the fact she didn’t say no on the spot was a victory. I remember just laying on a park bench that night, listening to music, just being so happy.

Her answer was ultimately a no. I wish that had been the end of it. Unfortunately, my immature self interpreted her offer of “Let’s be friends” to “Let’s hang out all the time (and maybe I can win you over),” and when she kept putting it off, I became clingy and she had to remind me not to misread the situation.

I look upon that rejection very fondly. It was the first of many. Now, I’ve more or less achieved that dream of immunity I told my high school best friend about. My dating days aren’t over, but the most insecure era is certainly over (or is it?). I like to think it’s confidence as opposed to not being able to care that much anymore. Fundamentally, though, is there a difference?

Rejection builds character. I like to think it has done so in my case. But I do worry that young people today are so bombarded with rejections every day, and when their self-esteem is at their lowest, some opportunistic online personality or trend or movement will give them crippling and/or easy answers and they’ll forever be in a stunted state.

I don’t relish the idea of books as tools for societal improvement. But I do hope that well-written yet brutally honest books like Rejection can, despite their apparent bleakness, help people make sense of their lowest and most embarrassing personal moments. And writers like Tulathimutte are making an admirable sacrifice, potentially sullying both their public and personal images, to provide that assistance.

For The Boys by me

An Acerbic Young Writer Takes Aim at the Identity Era | The New York Times Magazine

Why So Many People Are Going “No Contact” With Their Families | The New Yorker

i'm on record as a huge tulathimutte fan -- i think he's one of the best + most important fiction writers working, and has been for some time. the sexual mores of millennials are ripe for satire, and are remarkably under-discussed in contemporary fiction. but i sense a growing slipperiness about his work, to the extent i find he undermines his own subject matter.

like, when The Feminist was published -- the fact that he felt compelled to go on record and say hey, this is a work of fiction, im not endorsing this character? online publishing is a fraught space, but you can stand by your work. i find that story wildly observant, humorous, brave in its way -- but also kinda toothless? the clinical narration bestows objectivity, and the story is weaker for it. there's no real effort to inhabit the character, because that might imply sympathy.

and it's clear to me tulthimutte *is* sympathetic, in some form, to these emasculated rejects, that he considers them a silent majority of sorts, that smartphones + dating apps + wellness culture have further marginalized + radicalized them. yet there's always plausible deniability baked into his framing: we should recognize his characters, but we should also laugh at them. we may relate to certain experiences, but we should not seriously entertain their ideas. by virtue of reading his stories, we are rendered superior. the New York Times can safely print a glowing endorsement.

that's how satire -- and fiction more broadly -- works. i guess there's a tendency to moralize given the amoral subject matter. but it makes me question the medium. if these themes + characters are so important to entertain, they shouldn't be so easy to dismiss. surely there's a way to broach these phenomena without seeming reflexively sympathetic to like, incels and pickup artists and the like

Devoured Rejection in a day. I read Private Citizens a few years ago, and remember thinking the first 2/3s was great, and that the final act being a total mess.

As far as literary merit goes, Rejection felt much stronger than PC- the short story form really allows for just enough exposition without getting too bogged down in plot, and lets the characters shine without becoming caricatures of themselves.

I loved the first four stories. I felt seen in each one of them. I spent all of my 20s and half of my thirties single and dating, and I have been a version of Craig, Alison, Max, and even Neil! - and I think that’s why they resonated with me so much.

Main Character is the one I want to reread the most, though. No one has figured out how to write the internet experience very well (Patricia Lockwood tried and failed, Lauren Oyler tried and failed, Honor Levy…might do it?), but Tulathimutte seemed to capture (for me at least!) how obsessed and deranged twitter can make a very type of person.