The Only Good Narcissism is My Narcissism

'Didi,' Holden Caulfield, and other flawed protagonists in coming-of-age narratives

Warning: This piece contains spoilers for Didi.

Like clockwork, every few months or so, there’s some online litnerd squabble about The Catcher in the Rye, where it’s said that anyone who likes and identifies too much with Holden Caulfield and his supposed privileged self-obsession must be a walking red flag. I’ve always found this discourse irritating, even though I don’t like that novel (or Franny and Zooey) all that much and I am no Salinger fanboy. Recently at a karaoke bar, I was talking to a woman who said her name was Esme and that she’d been named after a literary character. I asked if her parents were big fans of Twilight and she gave me a look and said no, she’d been named after the Salinger character.1

So my annoyance is more because I don’t think these critics of The Catcher in the Rye have a problem with self-involved narcissistic protagonists. Rather, they just want their own narcissism to be in the spotlight. It’s the logical extension of that fake Marilyn Monroe quote about how those who can’t handle you at your worst don’t deserve you at your best. In a culture that values attention above all else, the privilege to be a narcissist—a beautiful monster, if you will—is the greatest privilege of all.

I don’t have anything against narcissism, at least in art. When combined with self-awareness, narcissism can be fuel for great creations. And all writers are narcissists to some degree anyway. But who has the nerve to bring that vision into fruition? This is why the movie Didi, written and directed by Sean Wang, fascinates me so much. When so much of Asian American art is obsessed with either begging for sympathy or avoiding the stirring up of any negative feelings,2 it has the gall to tell a coming-of-age narrative about an Asian American boy (Chris “Didi” Wang, played by Izaac Wang) who is unlikable for a significant portion of the film.

I purposely went to see Didi alone because I’d heard the main character would often be difficult to sympathize with. What if he reminded me too much of myself? We even have the same first name. But still, there are some key differences between Didi and me. The movie is set in 2008, when Didi is about to start high school. By then, I was in college. He’s Chinese American, whereas I’m Korean Canadian. He has an older sister, whereas I have a younger brother. However, Didi is about the closest approximation of my own upbringing I’ve seen yet and if I was going to cringe, I was determined to do it in solitude.

Didi’s storyline is pretty mundane. It takes place in the summer of 2008, when Didi is about to make the transition into high school. Growing up in Northern California, Didi is the younger child of a Chinese American family that’s headed by a de facto single mother, Chungsing Wang (Joan Chen). His father is absent with no timetable to return. He also has an older sister, Vivian (Shirley Chen) with whom he’s constantly fighting, and Chungsing’s mother-in-law, Nai Nai (Chang Li Hua) also lives with them. The movie is set almost entirely within that summer as Didi goes to parties, takes up skateboarding, pursues a crush, feuds with his family, and undergoes all the other usual rites of adolescence.

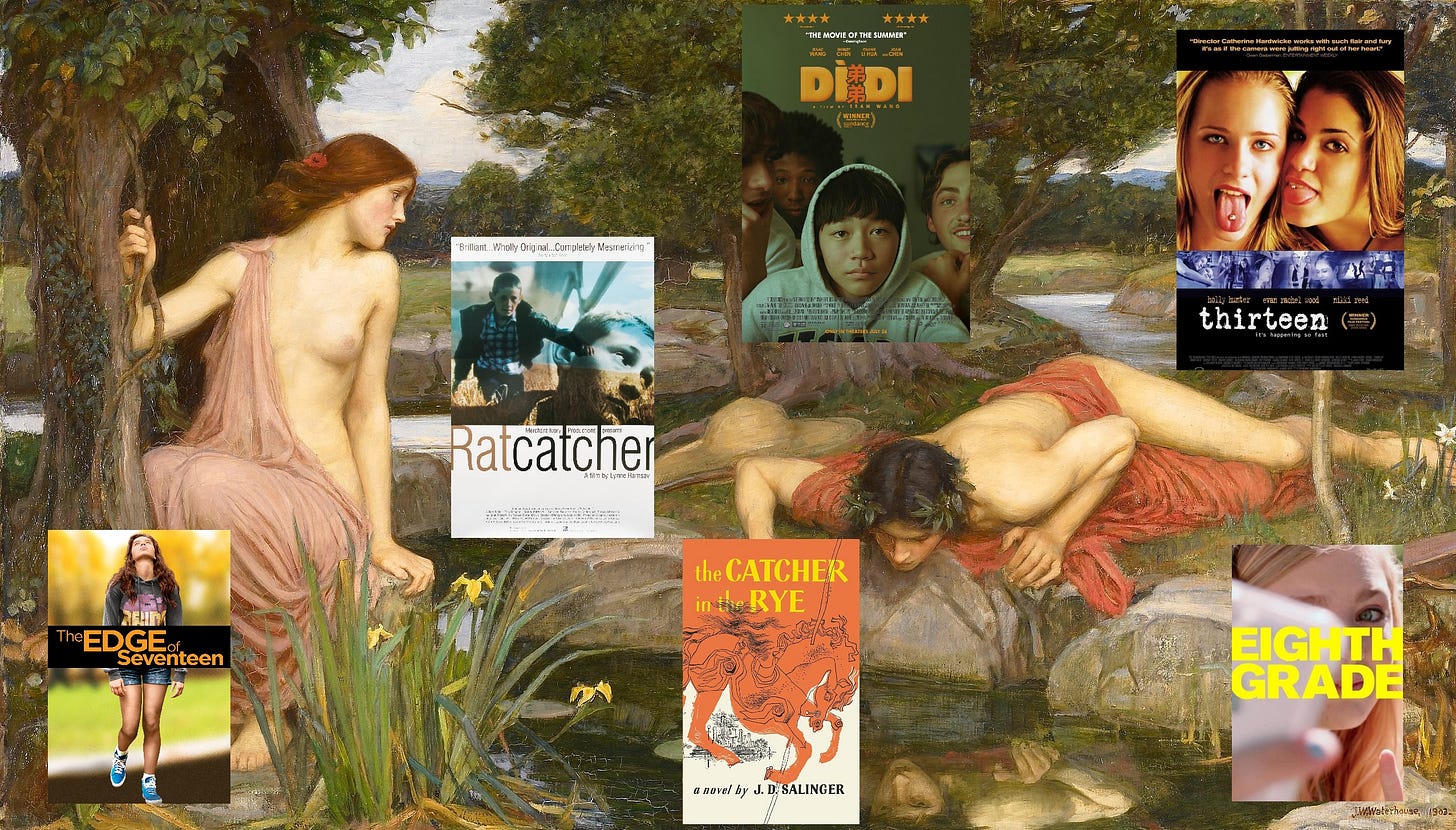

In a short introduction to the movie, Wang cites various influences, such as Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher. Other more recent comparable movies are Boyhood, Eighth Grade, and Thirteen. But the difference between all those and Didi are that the young protagonists of those coming-of-age movies are more clearly casualties of a cruel world. Mason in Boyhood is a quiet and sensitive kid who has to observe his mom struggle through single motherhood as she tries to make ends meet, gets involved with bad men, and eventually confronts empty-nest syndrome. Kayla in Eighth Grade can be seen as a victim of a contemporary society that compels children to be online too early in their lives and isolates them in the process. Thirteen depicts an overly sexualized culture preying upon young girls like Tracy, Antoine’s parents and teachers in The 400 Blows are tyrannical and/or selfish, and while James in Ratcatcher accidentally kills another boy, the audience is meant to see that as also a tragic commentary on the socio-economics injustices that befell working-class families in 1970s Glasgow.

On the other hand, Didi is not subject to such hardships. His family isn’t wealthy, but he grows up comfortably in the suburb of Fremont. His mother is attentive, his grandmother dotes on him, and though he is a racial minority, his social environment is very diverse (his two best friends, Fahad and Soup, are Pakistani and Korean American, respectively). Didi struggles academically, but not to the point where his teachers abandon him as a lost cause. When Didi approaches some older skater kids in hopes of being friends with them, they eagerly accept him as their video guy.

Yet for most of the movie, Didi is sullen and taciturn. His awkwardness is initially kind of wholesome, making him relatable to all of us who’ve suddenly seized up when in the vicinity of our crushes during our teenage years. The object of Didi’s affection is a girl named Madi, a popular girl who’s a year older than him but with whom he nevertheless has a shot because she has, according to his friends, yellow fever. His friends turn out to be right, but even when she’s blaring out signals that she’s interested, Didi freezes up, culminating in a moment of PG-rated sexual embarrassment.

So what exactly is Didi up against? In an interview with The Guardian, Wang said he wanted to make a movie about “shame, a corrosive feeling that crept into his life when he was made painfully aware of the stereotypes others placed on him due to his race.”3 In that same interview, Wang recalls an incident when a girl told him he was “cute for an Asian,” which is verbatim what Madi tells Didi before she tries to kiss and touch him. Is this what causes Didi to shut down and give Madi the silent treatment afterwards for the rest of the summer? It’s never made clear, which likely reflects the confusion Didi must’ve felt in the moment. What she says is not exactly the worst insult since the alternative could’ve been her saying he was actually like most of the other Asian boys: ugly, boring, unexciting, etc. And if he were to complain to anybody, he’d likely just face scorn, indifference, or denial. Maybe a half-hearted there there.

There is one other notable instance when race comes to the forefront, when Didi oddly claims to his older skater buddies that he’s actually half-Asian. Granted, he’s high and drunk when he says it, but it also makes sense why he’d say that. For example, just check out the frequency at which half-Asian/half-white actors get cast in Asian male leading roles. The male racial hierarchy in America is obvious to everyone.

Despite relating to Didi on many personal levels, I also found myself growing so frustrated with him as the movie went on. For instance, though he and his sister’s relationship appears to be improving throughout the summer, he refuses to even hug her goodbye on the day she leaves for her first day of college. If he thought it’d be too corny to get all mushy, just write her a note or email or something? Or when given a chance to impress some girls in his friend group, he not only chooses to tell a completely inappropriate story, but also insults the girls afterwards. I was left thinking, ‘What the fuck is wrong with this kid?’

Strangely enough, it was at his moral nadir—when he explodes at his mom and says the most unfairly cutting things to her—that I finally started to warm up to him. Because for god’s sake, at least he did something, even if it was to cruelly take out all his anger on his mom. How better would his life have been if he’d just learned to communicate his thoughts and feelings better? In a previous instance, Madi messages him online, apologizing for being too aggressive that night and pleading him to just talk to her again. Didi types a message explaining that he’s just terribly embarrassed, which would’ve been a perfectly understandable, even endearing, thing to say. They may never have gone on another date together, but certainly, a friendship might’ve been salvageable. But instead, he tap-tap-taps backspace and blocks her.

The character Didi reminds me most of is Nadine from The Edge of Seventeen, who spends most of the movie being a moody nightmare to those around her (though the movie does give her a trauma backstory by opening with the loss of her father). I’ve never been a teenage girl so I was able to enjoy that movie with a certain level of emotional distance, but I’m sure many viewers who saw themselves more in Nadine found it an uncomfortably familiar watch.

Wang is 30, which puts him at the Young Millennial generational bracket. I’m glad he came through with a film like this because for the last decade or so, it seemed like every POC Millennial male group had its own piece to say about its everyday experiences except for straight Asian American men. I remember an interview in which Alan Yang, one of the co-creators of Master of None, said that he based his movie Tigertail on his dad instead of himself because he had a nice but boring life.4 That interview pissed me off so much. We’re starved for material here! What, because Aziz Ansari or Ramy Youssef or Donald Glover’s semi-autobiographical narratives were that much more interesting? And if your own personal life is so bland, then make something up! You’re not a documentarian! It just seemed like typical Asian American male spinelessness, masquerading as magnanimity.

Perhaps Yang (and others in similar positions) were worried about backlash. Even before the whole babe.net mess, Ansari faced criticism for his alleged male chauvinist ways in sidelining South Asian women, especially as love interests.5 Ramy also was critiqued for not focusing enough on Muslim women.6 Even a Marvel movie, Shang-Chi, got the same racial sibling rivalry treatment.7 Maybe Yang didn’t have the fortitude to face any of that.

But not Wang, and for that, I applaud him. Furthermore, by not engaging in narrative self-flattery or crowd-pleasing in a semi-autobiographical story, Wang is demanding respect. And to my pleasant surprise, audiences and critics are responding (Didi has received rave reviews and even won an award at Cannes). It opens widely this week and I highly recommend you watch it.

Didi isn’t quite the divisive and explosive Asian American work of my dreams (is it up to me?), but it’s an encouraging sign, like Beef. Asian American artists need to shed that quality of constantly looking over our shoulders for signs of approval or withdrawing into the safety of writing about the past. It’s why I hold Min Jin Lee’s Free Food for Millionaires in such high regard,8 more so than Pachinko, a book that’s been sitting unread on my shelf for years now. It’s why I roll my eyes at the supposed subversiveness of a novel like The Sympathizer because it’s easy to be anti-imperialist when it comes to something like the Vietnam War, where the consensus narrative has already been settled upon (at least in metropolitan progressive circles); but what about, say, contemporary cold war issues between America and China?

I’m thinking of an alternate-reality movie that Wang might’ve made instead of Didi, where it was set further in the past. Didi would get called commie or chink or told to go back to Asia and the audience would shake their heads. But that would’ve been too easy. Didi’s shame could be that he feels shame at all. Politically, he is told he’s got nothing to complain about because he’s basically white, only to then feel socially and culturally alienated precisely because it is made clear he is not. It’s a gnawing feeling, one that he can’t quite prove because there are few stats to quantify these things. Plus, he sees his more charismatic and well-liked friends like Fahad and Soup, so it’s probably all his own fault? Whom can he talk to about this? He’s second-generation American, so by definition, there are relatively few who have gone through what he’s going through. His immigrant father probably wouldn’t have been able to be of much help, but at least he would’ve been an older male figure. In Didi’s outburst against his mother, he claims he wishes he’d been raised by his dad, which is less an indictment of his mom and more a desperate expression of his own isolation.

I’d also like to make a special mention of Arielle Zakowski, the editor of Didi. Many have praised the authentic visuals and feel of the movie and significant credit must go to her. The usage of MySpace-era digital technology strikes just the right balance between lending the movie a distinctive period feel while not overdoing the gee-whiz nostalgia bait. Her husband, Dan Chen, is a friend of mine and another talented Asian American filmmaker (check out his short film Ella9 and feature documentary Accepted10).

Didi ends on a quietly realistic but still optimistic note, with Didi seemingly on the verge of establishing a new and better relationship with his mom. It avoids easy moralizing, instead letting the audience come to conclusions for themselves. In the middle of the movie, there’s a pivotal scene in which Didi stumbles upon a harrowing scene in which Nai Nai is unjustly hectoring his mom for being a bad parent, even blaming her for chasing her husband (Nai Nai’s son) away. Didi appears shaken by this and Vivian, in an act of big-sisterly love, takes him away. Didi doesn’t immediately change, but we get the sense that the seeds have been planted for him to mature into a kinder and more thoughtful young man, that things aren’t always what they appear to be and that he should try harder to not add onto the unseen problems faced by those who love him most. Maybe one day, he can even help them.

For Esmé—with Love and Squalor by J.D. Salinger. Though I haven’t read or watched Twilight, I did somehow know that Edward and Bella name their baby Renesmee after two different people, so I knew there had to be a character named Esme in the story.

Asian American Psycho by me

Alan Yang: ‘Tigertail’ Is “A Metaphor for How Immigrants Feel When They Come to This Country” | The Hollywood Reporter

What ‘Ramy’ Gets Wrong About Muslim Women | The Atlantic

‘Free Food For Millionaires’ Boldly Scrutinizes Asian Women and Men | Plan A Magazine

Accepted (Trailer) | Youtube

Chris I haven’t even read the piece yet but this headline is so good

Thanks for writing this piece! Although, everything I'm seeing about the movie indicates that the boy and his family are Taiwanese-American? The director certainly is.