The Devils Wore Prada (Because They Were Paid $5 Per Word)

'The Devil Wears Prada,' 'Sex and the City,' 'Bored To Death,' 'The Vanity Fair Diaries,' and the cost of losing aspirational literary culture

So you’re a writer in the year 2025. You’re still waiting for the 100-or-so (pre-tax) bucks to hit your bank account for the freelance piece that was published months ago. You’re revising your dating app profile, wondering whether putting “writer” is actually a net positive (‘Oh, you’re a writer? Like a blogger? Or… a Substacker?’). You’ve just read a really good new novel, but few have even heard of it, so you chat up the usual friends you discuss this with. You all like and hate the same stuff, though, so it’s always the same. But it’s still fun.

Every generation feels that they’ve just missed out on the best of times. Every preceding era was cooler, sexier, and more optimistic. I recently attended a discussion between Alex Kazemi and Douglas Rushkoff where Kazemi said we’re in an unprecedented era of nostalgia, especially for the 90s. That felt a bit self-centered to me. But is there some truth to it, especially in literary culture?

The Devil Wears Prada is one of my favourite movies, living on my hard drive as a handy comfort watch on any return flights to NYC (an easy way to kill about 2 hours). It doubles as not only a period piece of the 2000s (from its jaunty pop-rock opening sequence to its T-Mobile ringtones), but also as relevant commentary on the downfalls (and rewards) of ruthless careerism.

I’ve had the source novel by Lauren Weisberger for a while, though I don’t quite remember how I got it. I think it was at a book swap. Judging from the name on the inside cover, it was previously owned by an Allie Epstein. I don’t know any Allie Epsteins. Regardless, I’ve put off reading it because I’ve heard that the movie is superior. But books shouldn’t remain unread on shelves. There’s something poser-ish about that. So it was finally reading time.

What I’d heard was correct, and the book is missing everything that people love about the movie. Book Miranda is more of an unpleasant eccentric (with an incongruent penchant for fatty meats) than anything else, lacking Movie Miranda’s quotability, whisper-yelling, and deliveries of cerulean-inspired dressing downs of insubordinates.

Movie Emily is much meaner than Book Emily, but Movie Emily is so cartoonish in her meanness and devotion to her employer that she horseshoes herself into lovability. Book Emily comes off more as someone who’s just trying to do her job and gets righteously annoyed when Andy makes yet another personal call while fetching Miranda’s coffee.

Speaking of Andy, whereas Movie Andy is an idealistic journalist who wants to fight for the little guy, Book Andy is more literary-minded, and the novel ends with her getting a short story published. Book Andy is not very good at her job, which can be said about Movie Andy. But whereas Movie Andy takes it upon herself to become an elite assistant, Book Andy just mediocrely slogs along. Why doesn’t Book Miranda just fire her? Or for that matter, why’d she hire her in the first place? Unlike Movie Andy, Book Andy is never regarded by Miranda as the “smart, fat girl” who’s unlike all the other silly fashion-obsessed girls.

Movie Nigel is many people’s favourite character from the film. Who wouldn’t want a funny and talented mentor who will never hesitate in giving you a reality check? But Book Nigel is hardly even a background character, appearing only a couple of times to be ridiculous and shouty:

“YOU!” I heard from somewhere behind me. “STAND UP SO I CAN GET A LOOK AT YOU!”

I turned just in time to see [Nigel], who was at least seven feet tall, with tanned skin and black hair, pointing directly at me. He had 250 pounds stretched over his incredibly tall frame and was so muscular, so positively ripped, that it looked as though he might just explode out of his denim… catsuit?

I just can’t see this Nigel pulling off the “Wake up, six” speech as effectively.

Apparently, when The Devil Wears Prada was first published, Weisberger’s former managing editor at Vogue said that she was “a lovely girl, but not a great writer, poor thing.”1 The hilariously sneering putdown aside, it’s also a fact that a quippy fashion narrative is best told as a movie. My favourite scene from the film is when Andy heads to the Runway gala. It’s her own little debutante ball. The background song is perfectly chosen, with its hypnotically dreamy dance beat. Anne Hathaway looks amazing and when she gives that luminous wink to Nigel, I’m done for. It’s hard for a novel to replicate that.

But these differences weren’t the thing that stood out most from the novel. Rather, it was the way money was so haphazardly thrown around. The movie may depict a lavish world, but the book conveyed more of a sense of casual (and expensive) waste. Book Miranda orders multiple staggered breakfasts so that she won’t have a cold meal whenever it is she ends up arriving at the office. Private and first-class plane booking are bought and unused and bought again on a whim.

It’s a world that’s also encapsulated in Sex and the City, published in 1996 as an anthology of Candace Bushnell’s New York Observer columns that had run from 1994-1996. Weisberger based The Devil Wears Prada on her experience as an intern at Vogue in 1999, so though the novel and movie came out in the 2000s, they are both children of the 90s.

I enjoyed Sex and the City (book) more than The Devil Wears Prada (novel), and Sex and the City is also better than its TV show (which, admittedly, I’ve only watched about 3 seasons). It’s an intriguing melding of genres: not quite a novel, not quite a memoir. The narrator weaves in and out of the lives of characters as both a central and irrelevant presence.

One of my favourite parts is the second chapter (entitled “Swinging’ Sex? I Don’t Think So…”) when the narrator is invited to a secret couples-only sex club. In anticipation, she begins “imagining all sorts of things: Beautiful young hardbody couples. Shy touching. Girls with long, wavy blond hair wearing wreaths made of grape leaves. Boys with perfect white teeth wearing loincloths made of grape leaves.”

Then she actually goes to such a club, and instead of “steamy sex, the first thing we saw were steaming tables” with a sign hanging above that reads: “YOU MUST HAVE YOUR LOWER TORSO COVERED TO EAT” (I think Emily Post once wrote an article about that). And instead of young and hot couples fucking like in a softcore movie that used to play at 2 a.m. back in the cable days, she sees “blobby couples” on air mattresses and “many men who appeared to be having trouble keeping up their end of the bargain.”

The world of Sex and the City is undoubtedly an elite one: weekends in the Hamptons and Aspen, exclusive parties in Upper East Side townhouses, and social networks filled with celebrities. And in this ecosystem, there are writers galore. Obviously, there is Bushnell herself as the narrator. In her friend group are two journalists (Carrie and Charlotte) and a novelist (Magda). Another friend in the group, Belle, is a banker but she’s married to a novelist. This writerly crowd may not have the raw financial resources of their higher-earning counterparts, but they still move in similar—or even better—circles. Carrie’s friends include Amalita Amalfi, an international socialite. A typical 30-something white-collar employee is probably not getting invited to a Karl Lagerfeld party.

Since the book is focused on the dating lives of accomplished 30-something NYC women, there is much discussion of the men they tend to date. It’s the usual cast of elite eligible types: fund managers, movie producers, law firm partners, trust-fund loafers, (successful) artists, and so forth. But in this menagerie of men are writers, too. Nico, a friend of Carrie’s and a news anchor, has an ex-husband named Dirk who’s described as a “pale, stocky novelist who was considered potentially important for about ten minutes after his first book came out six years ago.” Capote Duncan “was the thirtysomething Southern writer who was always out with beautiful young girls” and “also dated and broken the hearts of women who were in their thirties and usually pretty accomplished at something besides looking good.”

An entire chapter, “Bicycle Boys,” is dedicated to bemoaning the irritating childishness of bookish men who never want to let go of their Oxford days/fantasies by graduating from pedals to motors. But the fact that this chapter exists is proof that this group is considered a desirable bunch; otherwise, nothing would be written about them in the first place. A friend of mine who’s a writer and a bicycle-rider, recently told me about how things didn’t work out with a woman he was talking to. He said she’d wanted someone with money. I joked to him about this very chapter in the book: he was born in the wrong era.

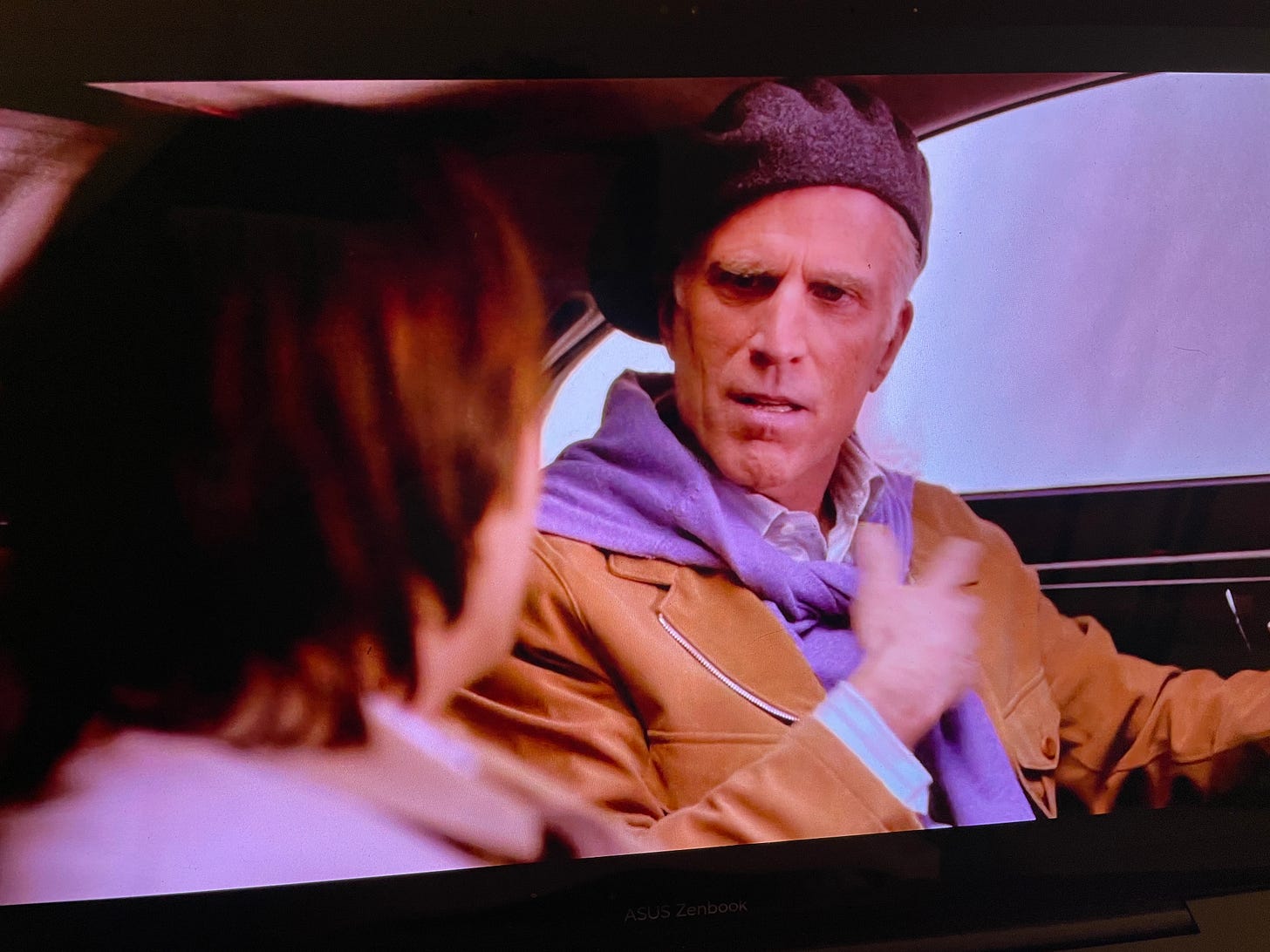

If Sex and the City represents the warm seasons of modern literary culture, with The Devil Wears Prada as its Indian summer, then Bored To Death is the chilly autumn leading up to Thanksgiving. It’s one of my favourite shows,2 an unfairly overlooked gem that lampoons the tweeness of 2000s Brooklyn (but focused on 30-somethings in Park Slope, rather than 20-somethings in Williamsburg). If you’ve ever wanted to see an insufferable Wes Andersonian protagonist (played by, who else, Jason Schwartzman) get told to shut the fuck up multiple times, this is the show for you.

Schwartzman’s character, Jonathan, is a struggling novelist whose money problems lead him to moonlight as an unlicensed private detective on Craigslist. Much of the comedy comes from how the effete and self-obsessed Jonathan is unsuited for his gritty new career, though he often finds a way to accidentally solve his cases.

Joining him on his adventures is George Christopher (Ted Danson), the editor-in-chief of a glossy magazine, Edition. What likely began as a professional relationship between Jonathan and George has become more of a father/son, as well as symbiotic, connection: Jonathan’s escapades (and pot stash) bring excitement into George’s life, while George’s money and influence bail Jonathan out from said escapades many times.

George—with his impeccable snow-white coif that almost makes you wish we could be born with such hair and “grey” into black/brown/blonde/ginger—is the best character on the show. An out-of-touch patrician libertine who seems to wear three-piece suits as pajamas, George’s narcissism is charmingly offset by his earnestness. In one scene, he laments the decline of Edition, especially with female readers:

George: Our biggest problem is our female demographic. We’ve lost over 37% of our women readers.

Jonathan: That is a lot of women.

George: I know.

Jonathan: So what’s the plan? Hire more women writers?

George: That’s a good idea, actually. That’ll be the second step. First step, though, is to change me. You see, if I’m right, then the magazine will be right.

Jonathan: But how are you going to change? You told me once that after the age of 55, it’s impossible to change.

George: That’s why my therapist is suggesting something radical. He wants me to experiment with bisexuality.

In the second of its three seasons, Bored To Death hits its peak, and uncoincidentally, it’s when the show is most immersed in the declining publishing industry. Jonathan’s just had his second novel rejected, forcing him to take on yet another job as a night-school creative writing teacher. Meanwhile, a fundamentalist Christian media group has taken over Edition, forcing not only financial cutbacks on George (he loses his precious paid-for table at The Four Seasons), but also the tempering of his Dionysian ways (e.g. regular drug tests). Amidst all this, there are George and Jonathan’s supremely petty fights with their rival counterparts, the editor Richard Antrem (Oliver Platt) and his toady, the writer Louis Greene (John Hodgman). If you love the spectacle of elitist pompous nitwits verbally slap-fighting each other—think Frasier or Trump’s “Sissy Graydon Carter” tweet—this is some of the best the sub-genre has to offer.

Sadly, in the third season, Bored To Death uproots itself from its satire of the literary world (Jonathan has published his second novel and George is now in the restaurant business) and focuses more on the zany hijinks of its main characters. The show loses most of its appeal and it’s apparent why it never got a fourth season. As Tina Brown writes in The Vanity Fair Diaries: “writers are the most disloyal, gossiping, and satirical crowd of any . . . always ready to sell out for a free drink.” Such fuel for funny.

I almost did not read The Vanity Fair Diaries, which had been recommended to me by a newly met acquaintance at a friend’s party in mid-March. The hardcover is a sizable 400+ pages, so as it moved at a glacial pace up my priority queue at the New York Public Library, I thought about simply referring to

’s excellent review3. But I’m glad I took the time to read it because it brought me full circle to The Devil Wears Prada, Sex and the City, and Bored To Death.I’ve always loved literature, but I was never deep into literary culture. I knew about authors, but not much about the editors, publishers, agents, art directors, etc. and all their industry intrigue. Yet these were all vital elements in not just creating literature, but also the alluring stage that so many writers want to find themselves upon. Things that vaguely made sense before came more sharply into focus after I read The Vanity Fair Diaries.

Such as why exactly George is so crestfallen when he loses his table at The Four Seasons. Early in her tenure at Vanity Fair, Brown writes about how she learns she is now too important to be seen at an upstairs (as opposed to main floor) table at The Four Seasons. Conde Nast’s editorial director, Alex Liberman, informs her: “My dear, you were in Siberia.” Later in the book, Brown notes how when Si Newhouse, the owner of Conde Nast, was not spotted dining at The Four Seasons for over a week, everyone noticed and were abuzz that he must’ve been off scheming on a major deal.

The Vanity Fair Diaries begins in 1983, in a society intoxicated and fattened by the tempting allure of Reaganomics. So many industries, including publishing, are flush with cash, and Brown illustrates a vividly beautiful picture of a bygone literary era as she writes about her treasured weekends away at Quogue, her newly bought and beloved Hamptons home:

It’s such a wonderful summer ritual, setting off from Penn Station on the Long Island Rail Road, changing at Jamaica, and gazing out the window all the way to Westhampton. That lonely sound of the train’s honky warning as it rounds the bend. The Ticket collector wears a boater and comes to each seat with sodas and chips. We always see the same people, editors and publishers with bags of manuscripts, spinsters with novels retreating to cottages in Sag Harbor.

Yet, as appealing as such scenes are, I couldn’t ignore the fact that Brown is a daughter of a successful movie producer, and much of her Vanity Fair was staffed with her Oxford friends, both of the literary and socialite types (often, there doesn’t seem to be much distinction). The loathsome Boris Johnson even makes an appearance, though to Brown’s credit, she instantly dislikes him: “But Boris Johnson is an epic shit. I hope he ends badly.”

So when Brown laments the sale of Tatler (the British magazine where she first began her editing career) to Conde Nast because it meant that her team of “ragtag renegades, flamethrowers at the black-tie balls” were now “part of the establishment,” I had to scoff: you all went to boarding school with Princess Diana!

But are things so different now? Do these intra-class wars among the elites ever end? No, they just morph. Instead of the titled nobility and debutante ball alumni, we have Silicon Valley oligarchs, social media clout-magnates, and Ivy League strivers who can weaponize social justice. And, of course, each of the aforementioned’s same-class critics and haters. All of us are the pompous nitwits in Bored To Death. Except now, a private equity firm has chopped up Edition into a ragebait TikTok account sponsored by Fan Duel.

A couple of things I’ve read and watched recently tie into all of the above. In the Compact piece, The Vanishing White Male Writer by Jacob Savage4, I was interested more on its focus on generation more than race and gender. By “white male writer,” Savage is talking more specifically about “straight white male Millennial writer”:

But white male millennials, caught between the privileges of their youths and the tragicomedies of their professional and personal lives, understand intrinsically that they are stranded on the wrong side of history—that there are no Good White Men.

I’m guessing Savage himself is part of this generation, making him naturally interested in its literary welfare. There is certainly a legitimate artistic concern for the lack of literary output by men (white or otherwise). But less discussed is how the disappearance of the male writer means that men have also lost an established avenue of accumulating status. The fixation on literary fiction may have an artistic basis, but surely, the fact that literary fiction has historically had the most glitziest social scene is relevant too. The Metropolitan Club doesn’t throw parties for genre writers.

And Millennials are the last generation of men to have grown up aspiring to climb these literary and societal ranks. I noticed how Savage doesn’t even bother to discuss Gen Z white male writers.

As the works discussed above show, becoming a writer meant possibly gaining access to high society. And for many kids who aren’t born into the elite, they may see writing—one of the most basic scholarly skills taught to us—as their pathway in. Andy in The Devil Wears Prada is likely one of these types: born to a nice Jewish family in New Jersey, she has a fanatical devotion to The New Yorker without showing much literary taste, which makes her veneration of the magazine similar to a computer science major idealization of Google.

For men, avenues like writing can be a way to pull ourselves up to the level of millionaires. In fact, we could even be superior to rich men. One chapter in Sex and the City focuses on the difficulties that successful older women in NYC have in finding a suitable husband because they’d rather not settle for “some boring bank manager who lives in New Jersey.” Maybe even a Bicycle Boy would be preferable.

In The Devil Wears Prada novel, the character of Christian Collingsworth is one of the most eligible bachelors in NYC, and the rare funny moment in the book for me—unintentional as it may be—is that he’s a novelist. In Bored To Death, the struggling and annoying Jonathan still has love interests played by Olivia Thirlby, Zoe Kazan, and Isla Fisher (if that’s not some wish fulfillment fantasy, I don’t know what is).

I’ve long thought that male comedians’ hostility to female ones was because comedy, especially stand-up comedy, is one of the very few areas where an unattractive and unpleasant man can actually leverage those otherwise negative qualities and become high-status. Women, in turn, want to have access to this ability to move up socially, and thus, the embittered comedy gender wars begin. Years ago when Jenny Slate and Chris Evans broke up, I remember seeing the online disappointment of so many women who’d admired how Slate had funnied her way to a classic hunk like Evans. Our dreams of social mobility aren’t just confined to moving into bigger houses.

The territory of the writing world, as with all artistic fields, has always been contested between the true craftspeople vs. the status-seekers. If for men, writing is now mostly only for the dedicated die-hards, that should only increase the quality of male writing. And the ones whose ultimate goal is not to write great essays and novels, but to sit on a perch where beautiful young ambitious women have to flirt—or even sleep—with them would be weeded out. Why should anyone mourn for these types?

Yet most people can’t be neatly divided into such extreme either/ors. The truth is that we’re all motivated in some part by status and respect. Writing for the sake of writing is a noble goal, but it’s also natural to want community and prestige while doing it. A lot of men also want our own share of drama. Just look at NBA fandom5. Many people have been confused at the seemingly bizarre contradiction of how such a queeny gossip like Trump is revered by so many self-proclaimed trad men. But these guys love Trump because of his decadent cattiness, not in spite of it.

recently posted a Note saying that complaining about the state of literature has reached a saturation point6. Nobody likes complainers, and people really don’t men who complain. So for the discontented, there is nothing left to do but write and create the literary culture they want to see. It’s for everyone’s benefit, because people want neither boorish nor bootlicking men, whether as friends, peers, or lovers.Take a step back, and you can see this longing for a lost literary culture is just part of widespread nostalgia. The Youtuber AmandaMaryAnna recently posted a video essay entitled “Gen Z vs Millennial Cringe,”7 which begins by documenting Gen Z’s online ire for things like Millennial burger joints8, and ends by citing envy as a motivating factor. As much as I deride the 2010s Buzzfeed era, I do acknowledge that it was the last time we felt at least somewhat optimistic about the future of media. In fact, it was precisely because we were so optimistic that we resented that era so much while we lived it; we feared it would just keep growing and take over. If we knew in advance how pathetically it would sputter out, maybe we would’ve been more chill.

Some pedestalize multi-martini sitdowns among the well-dressed at the Oak Room during some hazy period between the late 60s to early 2000s. Others glamourize Williamsburg circa 2012 with Gotye blasting out of some BBQ joint, where the one with the most Twitter followers is king/queen. You may greatly prefer one or the other, but at least both provided something and somewhere for which you could aspire. As Brown writes:

This is what I appreciate most about the city at night, the life force of New York aspiration, wanting, wanting to be seen. The erratic flames of the myriad glowworms—the striving fashion assistants, makeup artists, art gallery gofers, photography apprentices, gossip stringers, all the glamour wannabes dressed up with their “looks” in place. How they danced. How they gestured and waved and admired one another’s glad rags, cutting like flamoybant tugs through the sea of jaded vessels as the SS Jerry Zipkin and the SS Barbara Walters. This is the moment when the social energy of the city—in Diller’s word- metastasizes, when individual crassness and need are absorbed into the bedazzled, glory seeking hum of “Look at me! I’m alive!”

There’s a ton of talk these days about what’s ailing the youth (see Adolescence9). There’s no easy solution, and I’m obviously biased, but the cultivation of writing is surely one of the many things that can help.

I was recently invited to speak at a book club that had read my Asian American Psycho essay, and I found myself extolling the virtues of writing as character-building. It’s easy to learn, but difficult to master, meaning anyone can engage in it as a lifelong endeavour to better understand and express oneself. Ideally, writing—especially in longform—is the end result of your ideas that have passed through several internal mental processes. It’s not easy, but nothing worth doing is, a message that’s dangerously becoming less valued10. So what better goal could we have than to try to recreate a world that does more to reward reflection, hard work, and dedication?

The Untold and Very True Story of The Devil Wears Prada by Amy Odell | LitHub

If I recall correctly, I first watched Bored To Death in the months leading up to my move to NYC. It played some part in my initial, now baffling, decision to move to Cobble Hill. It’s a beautiful neighborhood, but once I moved in, I found it too quiet and isolated. Luckily, I was on a month-to-month with a fussy roommate who soon booted me out because he wasn’t “vibing” with me, an example of which, according to him, was my initial inability to follow his precise rules on how to fill out ice trays.

The Vanishing White Male Writer by Jacob Savage | Compact

Example of such tittering: Did you know that Jalen Green, the young Houston Rockets pseudo-star, has a stepson the same age as him?

“Writers are more visibly angry…” by Alex Perez

Gen Z vs Millennial Cringe by AmandaMaryAnna | YouTube

Not sure if these count as Millennial burger joints, but Nowon and Joe Jr. make my favourite burgers in NYC.

Adolescence is a well-acted show, but I’m always suspicious when a topical cultural work is so proclaimed by so many as being so utterly necessary, especially to the point of adding it to school curricula. Such reactions probably mean the book/movie/show isn’t actually challenging enough and comfortingly supports the audience’s existing beliefs. One of my biggest criticisms of the show is the 40-something detective-dad not knowing what the “red pill” was. If he’s in his 40s (like the actor playing him is), he would’ve been in his 20s when PUA culture took off in the 2000s. His generation invented the red pill! Elements like this just reeked of setting up a public service announcement.

Hard and Boring by me | Salieri Redemption

>The territory of the writing world, as with all artistic fields, has always been contested between the true craftspeople vs. the status-seekers... Yet most people can’t be neatly divided into such extreme either/ors. The truth is that we’re all motivated in some part by status and respect.

I've been having this argument with various people for years. It's easy to tell a romantic story about the lonely writer in his garret pouring his heart and soul out onto the typewriter and churning out masterpieces, while the dilettante who's only in it for the street cred can only put out derivative slush. Music critic and novelist Nick Hornby, in his book "31 Songs", once described an epiphany he had at a Patti Smith concert - he wrote that, watching her perform, for a moment he wished that the only people who would perform music were people who were as passionate about and emotionally invested in her music as Smith obviously was. But then he thought about it for a moment, and realised that this was ridiculous: some of his favourite songs were written by songwriters for whom composition was a day job, while there are scads of musicians who are incredibly passionate about the songs they write - but these songs suck. In the world of letters, it's trivial to find examples of beloved classics which were belched out by their authors for a paycheque (here's a good starting point: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/MoneyDearBoy), while probably no one is more emotionally invested in his "craft" than a housebound shut-in writing Sonic the Hedgehog fanfic.

So yeah, I'm profoundly suspicious of this idea that you can judge the quality of a book by how emotionally invested in its creation the author was, or that an author being emotionally invested in a book is a prerequisite to that book being any good. Sometimes the cynical avaricious status-seekers are just better at stringing a sentence together than the people who only do it for the love of the game.

"I’ve long thought that male comedians’ hostility to female ones was because comedy, especially stand-up comedy, is one of the very few areas where an unattractive and unpleasant man can actually leverage those otherwise negative qualities and become high-status. Women, in turn, want to have access to this ability to move up socially, and thus, the embittered comedy gender wars begin."

Ages ago, I dated a (bisexual) female comedian.

She told me being funny got her girls, but no guys.

This means something. I'm not sure what.